# 3676

Despite calls by the Whitehouse’s PCAST (Presidents’ Council of Advisors on Science and Technology) Report To The President On US Preparations for the 2009-H1N1 Influenza to have at least some vaccine filled, finished, and delivered by September - according to the CDC’s director Dr. Thomas Frieden - vaccine deliveries are unlikely before mid-October.

This report from Reuter’s Maggie Fox.

No flu vaccines before mid-October, CDC predicts

Wed Aug 26, 2009 10:14pm EDT

By Maggie Fox, Health and Science Editor

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - Scientific advisers to President Barack Obama may have asked the government to speed up the availability of swine flu vaccines, but they are unlikely to be ready before October, the new head of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said on Wednesday.

And imperfect tests for the pandemic H1N1 virus means it will be impossible to get precise numbers on how many people are infected, said Dr. Thomas Frieden.

The expectation right now is to have somewhere around 45 million doses of vaccine available by mid-October, and that millions more doses will come available in the weeks that follow.

With nearly 50 days to go, and a good deal of uncertainty left in the manufacturing process, those numbers (and the delivery date) could fluctuate further.

Assuming that sizable quantities of vaccine are delivered to the states in mid-October, hundreds of state and local health departments will begin the enormous and complicated task of dispensing the vaccine into the arms of the most `at-risk’ Americans.

This priority group consists of roughly 42 million people.

Pregnant women (4 million)

Household contacts of Infants < 6 mos (5 Million)

Health Care Workers With Direct Patient Contact (9 Million)

Children aged 6mos – 4 yrs (18 million)

Children under 19 with chronic medical conditions (6 Million)

And no one knows how smoothly or quickly that will go.

Most people believe, erroneously, that once they get a flu shot they are protected from influenza. In truth, it is a bit more complicated than that.

Seasonal flu shots, when they are well matched to the circulating strain, produce reasonable immunity in healthy young adults between 70% and 90% of the time.

The immune response is generally not as robust in the elderly, younger children, and some people with chronic illnesses or compromised immune systems.

If the vaccine isn’t well matched, those numbers go down.

And it takes a couple of weeks after the flu shot is received before the body develops sufficient antibodies to ward off infection.

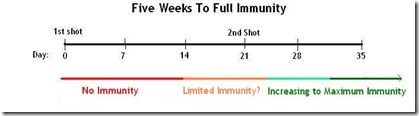

With a novel virus . . . or for a child getting their first seasonal flu shot, it generally takes 2 shots about 3 weeks apart, followed by another 2 weeks for the body to create antibodies.

There may be some limited immunity that develops a couple of weeks after the first shot, but maximum protection takes time to develop, and is expected about 2 weeks after a booster shot.

We are awaiting clinical trial data to tell us if 2 shots will be required with this new virus. For now, the assumption is that it will; at least for children and young adults.

For those who are able to get their first shot in mid October, followed by a second booster shot in early November, full immunity probably won’t develop until near Thanksgiving.

The big question facing public health officials is how fast can they get the vaccine out into the arms of the public, once the vaccine becomes available.

And no one really knows the answer to that.

It isn’t going to happen overnight, however. It may take weeks to get the first round of shots into those at highest risk, and months before everyone in the target group (159 Million Americans) that wants the vaccine, can get the vaccine.

Which means that `immunity by Thanksgiving’ meme we’re hearing this week is a best case scenario, and will only apply to a limited number of `high risk’ Americans.

A large number of Americans may not be offered the protection of a vaccine until after the New Year.

A vaccine is an important tool in our fight against this virus, but won’t be a panacea. And even those who are lucky enough to receive the vaccine will have to continue to take precautions because the vaccine isn’t going to offer 100% protection.

Many of us are likely to develop immunity the old fashioned way; through exposure to the virus.

But like a vaccination, the protection that affords will be temporary, as the virus will probably mutate over time and return next year, and probably in the years after that.

For now, and for the next few months, it will be the basic things – like hand washing, staying home if we’re sick, avoiding crowds, and covering our coughs – that will have the biggest effect on limiting the spread of this virus.

A vaccine, when it arrives, will no doubt help to protect those at greatest risk. But rolling out a vaccination program of this size is a huge task, and will take time.

The arrival of the novel H1N1 virus should be a wakeup call to our species. A new, potentially deadly virus can show up on our doorstep at anytime, and without warning. This time it was swine flu, and thus far, it is relatively mild.

Next time, it could be something worse.

The personal hygiene habits we are urged to adopt now are habits we should embrace all the time. And where our preparedness for this pandemic is shown to be inadequate or incomplete, we should rectify those problems now.

And lastly, we need to reevaluate our priorities, and give more thought (and funding) to public health in our country, and around the world. Preventing disease outbreaks is, in the long run, a lot less expensive than trying to deal with a pandemic.

While humanity is nearly 7 billion strong, we are still badly outnumbered by pathogens. We either get smarter about dealing with them, or we can expect to pay the price for our ignorance.