# 6215

With the announcement last fall that two researchers had successfully created a ferret-transmissible (and in one case, lethal), version of the H5N1 virus there have been fresh calls to regulate and restrict just how, and where, this sort of research should be conducted.

While not guaranteed - successful adaptation to ferrets (which have respiratory systems similar to humans) is assumed by many researchers to be a pretty good indication it would transmit in humans as well.

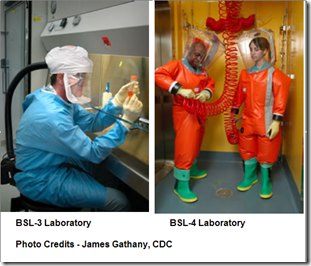

Suddenly labs that have been working with variants of the H5N1 virus are under new scrutiny, and regulators are questioning just how much biosecurity is needed to work on these viruses.

Last month Canada decided to restrict H5N1 research to labs with the highest biosecurity measures (see Canada Issues Biosafety Advisory For H5N1 Research), and other countries are considering similar measures.

In an attempt to assuage fears over the risks of H5N1 research (and the publication of the results), several well respected scientists have challenged the notion that the bird flu virus is as lethal in humans as is commonly portrayed.

One high profile paper appeared in Science last month -Seroevidence for H5N1 Influenza Infections in Humans: Meta-analysis - authored by Professor Peter Palese et. al., that argues that we are likely missing a great many uncounted H5N1 infections, and that the virus is far less lethal than has been assumed in the past.

This is similar to the argument that Vincent Racaniello offered last January in his blog Should we fear avian H5N1 influenza?

While stating that we don’t have definitive numbers, Palese writes that if one assumes a 1-2% infection rate among exposed populations, there would likely be millions of people who have been infected by the H5N1 virus.

Palese grants that deaths from the virus may also be undercounted, and calls for better studies (something that I think everyone, regardless of where they stand on this issue, would agree with).

A counter argument appeared last month in mBio, authored by CIDRAP director Michael T. Osterholm and Nick Kelley.

They found little evidence to support the notion that we are missing `millions’ of uncounted H5N1 infections (see mBio: Mammalian-Transmissible H5N1 Influenza: Facts and Perspective), and find that the H5N1 virus has the potential to be highly virulent in humans.

Mammalian-Transmissible H5N1 Influenza: Facts and Perspective

All of which serves as prelude to a new analysis, authored by Eric S. Toner and Amesh A. Adalja (both of the Center for Biosecurity at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC)) published last week in Biosecurity and Bioterrorism: Biodefense Strategy, Practice, and Science.

Is H5N1 Really Highly Lethal?

Eric S. Toner and Amesh A. Adalja.

Biosecurity and Bioterrorism: Biodefense Strategy, Practice, and Science. doi:10.1089/bsp.2012.022

I would invite you to read the entire study (it is reasonably short), but an excerpt from the press release sums it up nicely:

The authors review the available evidence: the distinctions between different clades of H5N1, the clinical series of human H5N1 cases, and the seroepidemiological and laboratory studies. They conclude that the preponderance of evidence argues that H5N1 virus is indeed highly lethal in humans compared to other influenza viruses.

Author Eric Toner said, “Our review of the evidence underscores what so many experts have been saying for years: Wild-type H5N1 is a very dangerous virus. We are quite fortunate it has not yet become contagious between humans.”

Dueling opinion pieces obviously won’t settle this argument, and regrettably, the amount of hard data available to support either position is limited.

While I suspect the virus is less deadly than the `official numbers’ suggest - given the stakes - it would seem to this humble blogger that if we err, we ought to err in favor of overestimating the threat of this virus.

At least in the short run.

We can always relax policies later when we have more accurate data and a better handle on the threat.

But underestimating this virus now, before we have solid answers, could lead to an irrevocable error.