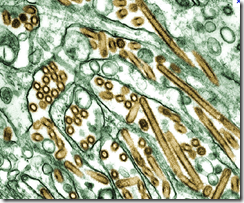

Photo Credit – CDC PHIL

# 8266

There’s a bit of controversy brewing today as it has emerged that 10 people in Korea – involved in the culling of poultry during H5N1 outbreaks in 2003 and 2006 - developed antibodies to the bird flu virus . . . yet were never admitted as having been `infected’ by the Korean government.

First the report (h/t Gert van der Hoek on FluTrackers) from the Korean Broadcasting System (KBS).

Asymptomatic Human Carriers of AI Confirmed in S. Korea

Write : 2014-02-04 09:09:57 Update : 2014-02-04 19:00:37

The government has confirmed it discovered cases of humans infected with avian influenza during previous outbreaks in South Korea.

The Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed ten people who culled birds during outbreaks in 2003 and 2006 had antibodies for the H5N1 strain of avian influenza.The discovery of antibodies in those people means they were infected with the virus at some point, but the disease control agency said they were “asymptomatic carriers” who displayed no symptoms.

The government confirmed infections of bird flu in dead migratory birds throughout the country last month.

Another report from the Korea Times today, brings us badly timed government assurances that the new H5N8 virus is `unlikely to infect humans’, as it also carries details of this story.

'Bird flu unlikely to infect people'

2014-02-04 16:55

(Excerpt)

It said that there have been no reported cases of human infection from other avian influenza subtypes in Korea, such as H5N1 and H7N9, which have killed people in overseas outbreaks.

However, concern is growing over the CDC’s methods of determining human infection.

The national disease control center follows the World Health Organization’s standard when it assesses a human infection case. The WHO determines a person has been infected with avian influenza only when they show symptoms of acute respiratory disease. People who are asymptomatic, even though the virus has infiltrated their body, are not deemed cases of human infection.

When the H5N1 strain swept the country in 2003-2004 and 2006-2007, the CDC found antibodies in the blood serum of 10 people who had slaughtered chickens.

The fact that they had antibodies shows that their immune system was countering a viral infection.

“Since those 10 people showed no symptoms, they were not counted as human infection cases,” an official at the CDC said.

There is admittedly a range of opinions when it comes to defining whether someone is – or has been – infected with by a virus, but one can’t help but feel that the `higher standard’ employed here was more for political expedience than for scientific merit.

When it comes to a virus like H5N1, there is considerable advantage in being able to say that `no human infections’ have been detected.

At issue is whether serological testing - testing for post-exposure antibodies - is a valid indication of viral infection. And given the emphasis we’ve seen on the need for serological testing to quantify the impact of just about every viral outbreak, you’d have to believe the answer is in the affirmative.

There are, of course, limits to serological tests, just as there are to PCR and viral cultures. No test is perfect.

Disagreements exist over what constitutes a `positive’ serological test (usually defined as a 4-fold increase in post-exposure antibody titer levels), and there are always concerns over potential cross-reactive antibodies and false positives.

But serological studies are generally regarded as the best way to determine the incidence of infection in a population, as you don’t have to depend upon a `perfect catch’ of a biological sample while the patient is actively shedding virus particles.

Not stated in today’s articles are the antibody titer levels detected in these 10 cases, so there could be some wiggle room there.

But it is also likely that these cullers were placed on Tamiflu while they were working with infected birds, which would probably have affected the antibody titers they developed, as well as suppressing any outward symptoms.

In the past we’ve often seen seroprevalence studies used to quantify avian flu infections in humans, including:

- Two years ago, in H5N1 Seroprevalence Among Jiangsu Province Poultry Workers, we saw a study that found across three locations tested (Gaochun, Jianhu and Gaoyou counties) the percentage of workers testing positive ranged from zero (Gaochun) to 5.38% (95%CI, 2.19%–10.78%) in Gaoyou.

- In 2011, a study (see Subclinical H5 & H9 Infections In Humans) tested 605 residents in and around Beijing China for antibodies to H5 and H9 avian flu viruses. Of these, just 5 (less than 1%) had antibodies to H9 avian influenza, and only 1 was positive for antibodies to H5.

- In May of 2009 (see Cambodian Study Finds Rare Asymptomatic H5N1 Infections) we saw a study published in the Journal of Infectious Diseases on more than 600 members of a Cambodian village where 2 human H5N1 cases were detected in 2006. Antibody titers showed that only 1% (7 of 674) of the villagers tested had contracted, and fought off, the H5N1 virus. A figure much lower than many had expected.

- J Epidemiol. 2008;18(4):160-6. Epub 2008 Jul 7. Human H5N2 avian influenza infection in Japan and the factors associated with high H5N2-neutralizing antibody titer.Ogata T, Yamazaki Y, Okabe N, Nakamura Y, Tashiro M, Nagata N, Itamura S, Yasui Y, Nakashima K, Doi M, Izumi Y, Fujieda T, Yamato S, Kawada Y.

- Arch Virol. 2009;154(3):421-7. Epub 2009 Feb 3.Serological survey of avian H5N2-subtype influenza virus infections in human populations.Yamazaki Y, Doy M, Okabe N, Yasui Y, Nakashima K, Fujieda T, Yamato S, Kawata Y, Ogata T.

So it is hard to argue that the detection of antibodies – even in asymptomatic cases – wasn’t worthy of mention, even if the official determination was they were not `infected’.

While hardly a game changer, and not terribly surprising given other H5N1 studies we’ve seen - this is scientific data and it should have been disclosed in a timely fashion - not held back for a decade.

If for no other reason than now – as Korea finds itself in the midst of another avian flu crisis – everyone will be wondering what other `hidden asterisks’ are attached to government assurances.

As I’m not a virologist or an epidemiologist, I’ll leave it to those more qualified to argue the relative merits of using serological test results, or the exclusion of asymptomatic cases, in case definitions.

Hopefully we’ll get far more expert reaction from Dr. Ian Mackay on all of this later today.

UPDATE: Ian has now posted his thoughts at:

Why have a case definition that seems designed to miss transmission events?