# 8937

The tragedy of healthcare workers exposed to Ebola continues to evolve in Nigeria as that country reports their 10th positive case – all apparently as a result of contact with the index case, a Liberian named Patrick Sawyer who fell ill while flying to Lagos 22 days ago.

Media reports suggest he told HCWs he had malaria, and became both erratic and combative when he was told he might have Ebola, thereby exposing more to the virus.

Whatever the circumstances (and Caveat Lector should be the rule when dealing with media reports) – the end result has been the infection of at least 9 additional people – with more either suspected or under observation. First a brief update from Reuters, then I’ll have a bit more.

Nigeria's Lagos now has 10 Ebola cases: health minister

ABUJA Mon Aug 11, 2014 3:18pm IST

(Reuters) - Nigeria's Lagos has 10 confirmed cases of Ebola, up from seven at the last count, although only two so far have died, including the Liberian who brought the virus in, the health minister said on Monday.

All were people who had had primary contact with Patrick Sawyer, who collapsed on arrival at Lagos airport on July 25th and later died, Health Minister Onyebuchi Chukwu told a news conference.

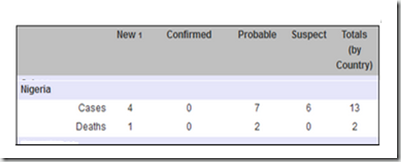

For those wondering why the number is now 10, when the World Health Organization and the media were reporting 13 cases on Friday – the answer is simple; Friday’s number was a combination of suspected, probable, and confirmed cases.

From WHO GAR update August 8th

While there are many who were alarmed last week by the deliberate importation to a high containment facility at Emory University Hospital of two Ebola positive patients, the events in Nigeria show the bigger risk to health care workers comes from having direct contact with someone they don’t know is infected.

Previously, the R0 or Basic Reproductive Number for Ebola has been calculated as being under 2.0. Essentially, the number of new cases in a susceptible population likely to arise from a single infection.

Chowell G1, Hengartner NW, Castillo-Chavez C, Fenimore PW, Hyman JM.

Abstract

Despite improved control measures, Ebola remains a serious public health risk in African regions where recurrent outbreaks have been observed since the initial epidemic in 1976. Using epidemic modeling and data from two well-documented Ebola outbreaks (Congo 1995 and Uganda 2000), we estimate the number of secondary cases generated by an index case in the absence of control interventions R0. Our estimate of R0 is 1.83 (SD 0.06) for Congo (1995) and 1.34 (SD 0.03) for Uganda (2000).

Making the number of secondary cases reported in Nigeria from a single case unusually high, although you cannot extrapolate the R0 off a single transmission event.

Each link in the chain of transmission is different, and the R0 is only an `average’ over time.

During the SARS outbreak of 2003 (a much more contagious respiratory virus), studies found most infected persons would only infect 1 or perhaps 2 additional people, and sometimes none. But a small percentage of those infected were far more efficient in spreading the disease, with some responsible for 10 or more secondary infections.

This super spreader phenomenon gave rise to the 20/80 rule, that 20% of the cases were responsible for 80% of the transmission of the virus (see 2011 IJID study Super-spreaders in infectious diseases).

While it might be tempting to ascribe the aggressive spread to HCWs in Nigeria to Sawyer being a `super spreader’, that isn’t the only credible explanation.

As any healthcare worker will tell you, trying to restrain or `take down’ a combative – sometimes irrational - patient is one of the most dreaded, and dangerous things they may be called upon to do.

The risk of physical injury to the HCW, and to the patient, is greatly increased, as are the risks of exposure to blood or other body fluids. Protective gear – if worn – can be quickly damaged or compromised .

And since Healthcare workers are limited as to how much force they can ethically use to restrain a patient – a constraint not usually honored by the patient – it often requires 3, 4, 5 or even more people to subdue someone without injuring them.

This may help explain, at least in part, how so many HCWs have become infected from exposure to a single Ebola case.

I would note that there are media reports (see Nigerians beg Obama to give Lagos nurse vaccine) that at least one of the Nigerian nurses infected did not participate in restraining Sawyer, but did perform routine nursing duties (taking vitals, feeding the patient, etc.) and touched some of the same surfaces as the patient.

What PPEs she may have employed while performing these duties, and the veracity of these media reports, isn’t abundantly clear.

A detailed epidemiological investigation into the chain of transmission in Nigeria ought to give us a better idea of exactly what happened there. Where infection control procedures broke down, whether Sawyer was a `super-spreader’, or if the staff was simply blindsided by combination of bad luck and timing.

Hopefully that investigation is underway, and the results will be forthcoming sooner rather than later.