WHO December Update

# 9425

While Ebola and MERS have garnered much of the infectious disease attention over the past year, in terms of having pandemic potential, novel influenza viruses remain atop the list of viruses of most concern.

Over the past 125 years we’ve seen 6 pandemics arise, all presumably from reassortant avian or swine influenza viruses.

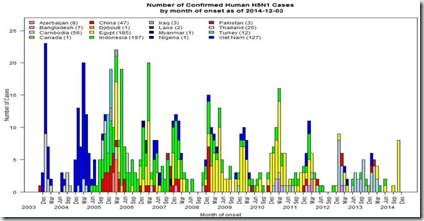

Of the novel viruses circulating in the wild, up until a couple of years ago, the avian H5N1 influenza virus was our primary concern. After being beaten back in Hong Kong in 1997, it re-emerged in 2003 and since that time has killed millions of birds, and has been known to have infected more than 675 people – killing roughly 60% of them.

Over the past couple of years H5N1 has taken a backseat to a new arrival; H7N9, which appeared in the spring of 2013 in Eastern China and has infected roughly 450 people over its first two waves. Seemingly better adapted to mammals, H7N9 is now considered the bigger threat, although H5N1 continues to circulate and occasionally infect humans.

We’ve also seen swine variant viruses (H1N1v, H1N2v, H3N2v) jump to humans, along with some very sporadic infections by H5N6, H9N2, and H10N8 avian viruses.

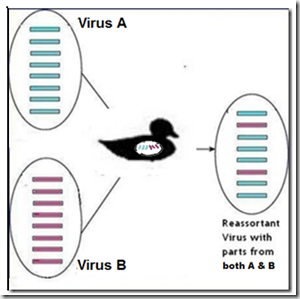

There are literally dozens of influenza subtypes circulating in birds, swine, horses, dogs, and even marine mammals that – while not currently a danger to humans – have at least some potential to evolve or reassort into a public health threat. Most will never make that leap, but it is impossible to predict which ones will.

Reassorted viruses can result when two different flu strains inhabit the same host (human, swine, avian, or otherwise) at the same time. Under the right conditions, they can swap one or more gene segments and produce a hybrid virus.

Because of its perceived `higher risk’, the World Health Organization reports separately on H7N9 cases, but now lumps the H5N1 and other novel flu viruses into an irregularly scheduled report called Influenza at the human-animal interface.

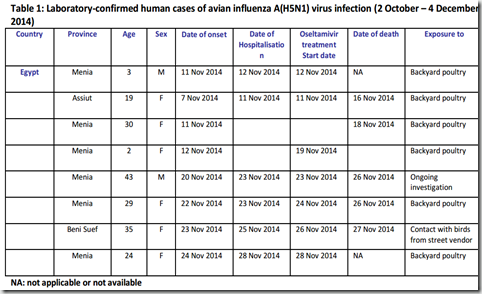

The latest version is dated December 4th. After a very quiet summer, over the past three weeks we’ve seen a sharp increase in H5N1 cases in Egypt, and the WHO update details 8 of them.

We’ve seen three more cases reported since this chart was created, and this morning are watching numerous reports out of Egypt of `suspected’ cases being tested. As this is `cold & flu’ season, it is likely that many of these suspect cases will have something less exotic than H5N1, but we’ll have to wait for the results.

The WHO assessment on the threat of H5N1 reads:

Overall public health risk assessment for avian influenza A(H5N1) viruses: Whenever avian influenza viruses are circulating in poultry, sporadic infections or small clusters of human cases are possible in people exposed to infected poultry or contaminated environments, especially in households. Human infections remain rare and these influenza A(H5N1) viruses do not currently appear to transmit easily among people. As such, the risk of community-level spread of these viruses remains low.

Of note, the WHO also reports on a couple of novel swine H1N2 infections from Sweden.

Human infection with influenza A(H1N2) reassortant viruses

Since 2013, a reassortant influenza A(H1N2) virus has been identified on a swine farm in Sweden. In April 2014 this virus was detected in nasal swabs from two swine farmers in Sweden, during the course of a study of influenza viruses circulating in swine and people in contact with swine. The virus detections in the swine farmers occurred after the same virus had been detected in swine at the farm where the two human cases worked.Both human cases were asymptomatic, and no further human infections have been detected among other farmers or family members. The genetic analysis of the viruses so far shows that 7 genes of the virus, including the haemagglutinin (HA) and all internal genes, are closely related to the A(H1N1)pdm09 virus. The neuraminidase (NA) is derived from a human influenza A(H3N2) virus. This gene has been circulating among pigs in Sweden since 2009. Virological characterization is ongoing.

Over the past several years we’ve been watching several swine variant influenza viruses – H3N2v, H1N1v, H1N2v – making tentative jumps into the human population (see Keeping Our Eyes On The Prize Pig) and each summer the CDC issues advice on preventing infection at county and state fairs (see Measures to Minimize Influenza Transmission at Swine Exhibitions, 2014).

The WHO report concludes with:

Outbreaks in animals with avian influenza viruses with potential public health impact

The number of reported outbreaks of avian influenza in birds globally is currently at the level expected during this period of the year.

Owing in part to the emergence of avian influenza A(H7N9) virus, there is enhanced surveillance for nonseasonal influenza viruses in both humans and animals. It is expected that influenza A(H5N1) and A(H7N9) will continue to be detected in humans and animals over the coming months. In addition, various other subtypes, such as influenza A(H5N6), A(H5N8), A(H5N2), A(H5N3) have been detected in poultry recently, according to reports received by OIE.

Due to the constantly evolving nature of influenza viruses, WHO continues to stress the importance of global surveillance to detect virological, epidemiological and clinical changes associated with circulating influenza viruses that may affect human (or animal) health, especially over the coming winter months.

All human infections with non-seasonal influenza viruses (those that are not currently circulating widely in human populations) are reportable to WHO under the IHR (2005). It is critical that influenza viruses from animals and people are fully characterized in appropriate animal or human health influenza reference laboratories.