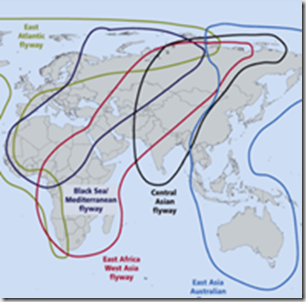

Major Global Migratory Flyways – Credit FAO

#10,361

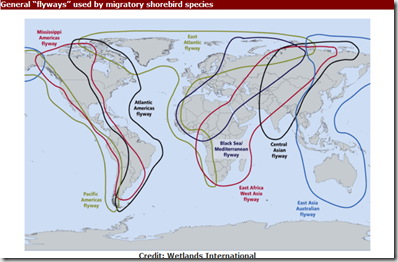

A decade ago, when H5N1 was making its first forays into Europe and the Middle East, concerns ran high it might hitch a ride on migratory birds and make its way to the Americas. As the map above illustrates, there are two major `shared’ migratory flyways which could plausibly provide a bridge for avian flu from either Europe or Asia.

- The East Atlantic Flyway extends from Northern Canada to Northern Europe and Russia and runs all the way down to the southern tip of Africa, while overlapping two major Eurasian flyways (see PLoS One: North Atlantic Flyways Provide Opportunities For Spread Of Avian Influenza Viruses).

- .The Pacific Americas Flyway overlaps with both the Central Pacific and (more importantly) the Asian-Australian Flyways in Alaska and Siberia

While primarily north-south migratory routes, these flyways all overlap, and therefore allow for lateral (east-west) movement of birds as well. A good example this comes from our own Arctic Refuge, where more than 200 bird species spend their summers, and then head south via all four North American Flyways each fall.

Credit FWS.GOV

In 2008, a USGS study found Genetic Evidence Of The Movement Of Avian Influenza Viruses From Asia To North America, where we saw evidence that suggested migratory birds play a larger role in intercontinental spread of avian influenza viruses than previously thought.

A couple of years later, in Where The Wild Duck Goes, we looked at a USGS program that used Satellite Tracking To Reveal How Wild Birds May Spread Avian Flu.

For reasons that remain obscure, in 2007 the aggressive global expansion of H5N1 halted, and over the next few years we saw a retreat of the virus from across much of Europe, with most of the activity centered around Asia, India, Indonesia, and Egypt.

While concerns over H5N1 winging its way to the Americas didn’t go away, they were at least dampened.

Although research has continued to implicate wild and migratory birds as vectors of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) viruses, the idea has not been without its critics.

For years we’ve heard from some experts that `Sick birds don’t fly’ , even though it has been well established that some bird species can carry HPAI viruses asymptomatically (see Webster On China's `Silent' Bird Flu Infections). A few notable dissenting voices include:

- In 2009, in India: The Role Of Migratory Birds In Spreading Bird Flu, we saw an expert committee declare that migratory birds were not responsible for the spreading of H5N1 in India and neighboring countries.

- While in Another Migratory Bird Study, a paper appeared in the British Ecological Society's Journal of Applied Ecology in 2010, that claimed that the global spread of the H5N1 virus through migratory birds was possible . . . but unlikely.

- In January of 2014, in response to the South Korea assertion that Migratory Birds Likely Source Of H5N8 Outbreak the Scientific Task Force on Avian Influenza and Wild Birds quickly issued a statement saying:

1. Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) outbreaks are most frequently associated with domestic poultry production systems and value chains.

2. H5N8 HPAI virus has recently emerged in domestic poultry in the Republic of Korea and has caused mortality of domestic poultry and wild birds.

3. As well as impact on the poultry industry, there is the potential for significant mortality of wild birds most notably in large flocks of Baikal teal.

4. There is currently no evidence that wild birds are the source of this virus and they should be considered victims not vectors.

We’ve explored this often bitter debate between the poultry industry and conservationists a number of times (see Bird Flu Spread: The Flyway Or The Highway?) and while poultry industry practices and poor biosecurity are no doubt major contributing factors for the spread of avian flu, it is hard to dismiss wild birds as being at least partially responsible, particularly for long distance jumps of the virus.

For a full decade following the second emergence of H5N1 in Vietnam (2003), the bird flu scene remained fairly stable. There was HPAI H5N1, and a handful of lesser LPAI (low path) H5 and H7 viruses of concern (plus LPAI H9N2), but only one HPAI threat.

Things began to get messy in 2013, when a new LPAI H7N9 virus appeared in China. While it didn’t make birds sick, it was highly pathogenic in humans, and it has sparked three mini-epidemics since its arrival. Since it is asymptomatic in birds, it spreads stealthily in poultry flocks and live markets, making it very difficult to detect and control.

A few months later an HPAI H10N8 appeared in China, causing several deaths, followed by HPAI H5N8 which showed up in South Korean migratory birds – and commercial poultry – in January of 2014. Not to be outdone, a new H5N6 virus appeared in both China and Vietnam in the spring of last year, and much like H5N1, it can infect (and kill) humans.

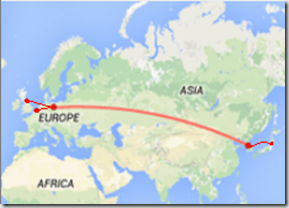

HPAI H5N8 quickly spread across China and into Russia, but a big surprise came last November when a farm in Germany reported the virus (see Germany Reports H5N8 Outbreak in Turkeys), followed 10 days later by reports from the Netherlands (see Netherlands: `Severe’ HPAI Outbreak In Poultry), and again from Japan (see Japan: H5N8 In Migratory Bird Droppings).

H5N8 Branching Out To Europe & Japan

Suddenly H5N8 was on the move, in a manner which we hadn’t seen since the great H5N1 diaspora of 2006 – when that virus sprang out of southeast Asia and moved into Europe, Africa, and the Middle East.

An even bigger surprise came when HPAI H5 virus literally jumped continents and turned up – first in Canada’s Pacific Northwest (see Fraser Valley B.C. Culling Poultry After Detecting H5 Avian Flu) in early December – and then began spreading across the western United States (see EID Journal: Novel Eurasian HPAI A H5 Viruses in Wild Birds – Washington, USA).

.

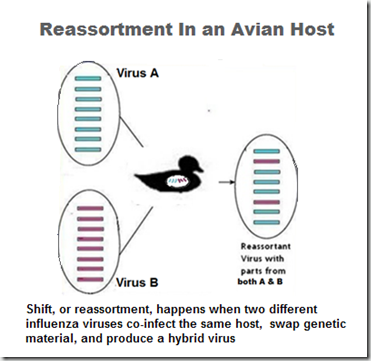

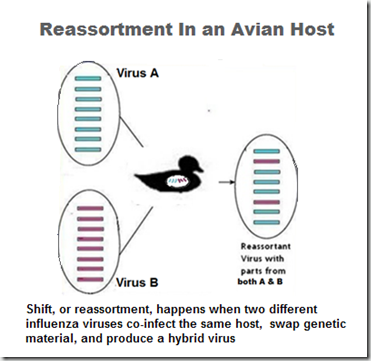

As H5N8 arrived in Taiwan, Canada, and the United States, it has reassorted with local LPAI viruses and produced unique reassortant viruses (H5N2 and H5N1 in North America, H5N2, H5N3 in Taiwan).

How viruses shuffle their genes (reassort)

Not only has H5N8 proved to be an able hitchhiker aboard migratory birds, it appears to reassort easily with other LPAI viruses, and has churned out a remarkable number of viable offspring in a short period of time.

Of these, H5N2 has spread the fastest, and caused the most damage to the poultry industry. But the possibility of seeing additional reassortments emerge in the years to come is real, and their behavior – and their pathogenicity in birds and humans – is quite frankly, impossible to predict.

The $64 question is what comes next.

And quite frankly, no one knows. In 2007, just when it looked as if H5N1 was on the verge of becoming a global threat, it unexpectedly began to wane. The same thing could happen again, although this time the HPAI bench is deeper, as it includes H5N1, H5N2, H5N8, H5N6, and H7N9 (among others).

The expectation is that H5N8/H5N2 will return with the fall arrival of migratory birds, and if farm biosecurity measures aren’t effective - we could see a repeat of this past spring – except more states and more farms are likely to be impacted.

If that happens, it could cost the poultry industry billions, which is why on Tuesday, Secretary of Agriculture Vilsack will be meeting with state and local officials, and representatives of the poultry industry, in Des Moines, Iowa to discuss preparing for this exact possibility.

There are other scenarios, of course.

- The most dire (but hopefully the least likely) being H5N8 or H5N2 evolve to the point they could pose a human health risk. For now, the risk of infection from these viruses is deemed low by the CDC (see EID Journal: Infection Risk To Those Exposed To HPAI H5 Viruses – United States). Other plausible scenarios could involve new reassortant subtypes emerging from the interaction of H5N8/H5N2 with other native LPAI viruses. Already we’ve seen an EA/NA version of H5N1 (see USGS: Genetic Analysis Of North American Reassortant H5N1 Virus From Washington State), as the result of ongoing reassortment. And now that H5N8 has demonstrated it can be done, we need to be open to the possibility that other HPAI viruses may make the trek from Asia or Europe via migratory birds in the years to come. A threat that looms larger with each new avian flu subtype that emerges in Asia.

The same avian flu scenarios facing North America this fall and winter pose similar threats to much of Europe, Africa and the Middle East. Only the flyways that will serve as potential bird flu conduits differ.

If there are any doubts remaining over the role that migratory birds are playing in the spread of avian flu viruses, with the scrutiny they will get this fall and winter (see APHIS/USDA Announce Updated Fall Surveillance Programs For Avian Flu), there’s a pretty good chance they will be resolved over next 6 months to a year.

For more on the spread of avian viruses across long distances by migratory birds, you may wish to revisit:

Erasmus Study On Role Of Migratory Birds In Spread Of Avian Flu

PNAS: H5N1 Propagation Via Migratory Birds

EID Journal: A Proposed Strategy For Wild Bird Avian Influenza Surveillance