Credit Florida DOH

# 10,238

A couple of weeks ago, in Naegleria: Rare, 99% Fatal & Preventable, we looked at an freshwater pathogen that can cause an exceedingly rare brain infection if absorbed through one’s sinuses.

Caused by the amoeba Nagleria Fowleri, the disease is called PAM (Primary Amoebic Meningoencephalitis), and it is almost always fatal.

It is most often acquired by swimming in warm, stagnant freshwater ponds and streams, but has also turned up occasionally in public water supplies (see A Reminder About Naegleria & Neti Pots & Naegleria Fowleri).

Several states (including Florida) promote Naegleria awareness each summer, but one of the best resources available online is http://amoeba-season.com/, a USF Philip T. Gompf Memorial Fund project, which was set up by a pair of Florida doctors who tragically lost their 10 year-old son to this parasite in 2009.

Saltwater, too, can harbor dangerous pathogens.

One, called Vibrio, is a naturally occurring bacteria that can be most commonly be found in the warm coastal waters of the gulf coast states (Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Texas and Mississippi), between May and October.

While there are at least a dozen strains of Vibrio (including Vibrio cholerae), the two we concern ourselves with most this time of year are Vibrio vulnificus and Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Both are halophilic (`salt loving’), thrive in warm brackish water, and can infect humans via open wounds or through ingestion.

Of the two, Vibrio parahaemolyticus is by far the most common, but is usually a milder infection. It most often occurs through the consumption of undercooked shellfish, or the ingestion of contaminated seawater, although skin infections are possible. The CDC describes the illness as:

When ingested, V. parahaemolyticus causes watery diarrhea often with abdominal cramping, nausea, vomiting, fever and chills. Usually these symptoms occur within 24 hours of ingestion. Illness is usually self-limited and lasts 3 days. Severe disease is rare and occurs more commonly in persons with weakened immune systems. V. parahaemolyticus can also cause an infection of the skin when an open wound is exposed to warm seawater.

The 2014 MMWR Notes from the Field: Increase in Vibrio parahaemolyticus Infections Associated with Consumption of Atlantic Coast Shellfish — 2013 estimates in excess of 35,000 – mostly mild - V. parahaemolyticus infections occur each year in the United States.

Although concentrations of V. parahaemolyticus are highest in the Gulf coast state’s waters during the summer months, they can become dangerously elevated as far north as the Pacific Northwest and the Northeastern Atlantic states.

Less common, but generally more serious are Vibrio vulnificus infections, which can occur after an open wound is exposed to waters where the organism is growing, or through the ingestion of contaminated seawater or undercooked shellfish.

Those with weakened immune systems are more likely to experience severe illness, and for those who develop sepsis, the mortality rate can approach 50%.

It should be noted that tens of millions of people swim and play in the Gulf and Atlantic coastal waters every year, and only a small handful are affected. Frankly, you have a far better chance of drowning than acquiring this bacterial infection.

Nevertheless . . . .

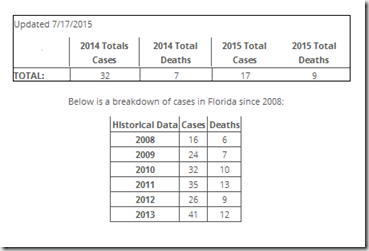

The Florida Department of Health reports the following epidemiological profile for V. vulnificus:

From 2000 to 2013, there has been an average of 28.4 V. vulnificus cases reported each year in Florida with a range of 13 – 46 cases. Most cases are reported during the months of May through October. Between 2004 and 2013, there were 1,235 cases of vibriosis reported in Florida and V. vulnificus accounted for 299 (24%) of those cases. During that time frame, there were 103 deaths reported due to vibriosis and V. vulnificus infections accounted for 88 (85%) of those cases.

For V. vulnificus cases, wound infections accounted for 50.5% of cases, seafood exposures accounted for 24% of reported cases and the remaining 25.5% had exposures that could not be classified due to multiple factors (unable to interview, had both exposures to seawater and raw seafood).

Cases were white (88.3%), non‐Hispanic (91%) males (86.3%).Data collected from 2008 to 2013 indicated that 35.4% of reported cases abused alcohol, 35.4% had liver disease, 27.4% had heart disease, and 22.8% had diabetes (systematic collection of risk factors was not collected record prior to 2008)4.

On Friday, the Florida DOH updated their Vibrio vulnificus case count for 2015, adding three more cases during the past 7 days.

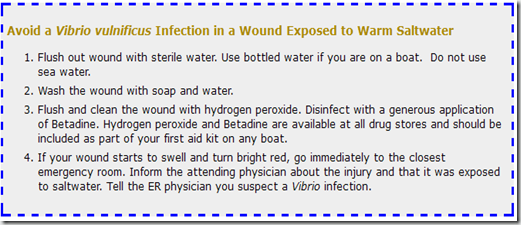

Florida’s DOH provides the following advice on how to avoid infection:

What are some tips for preventing Vibrio vulnificus infections?

- Do not eat raw oysters or other raw shellfish.

- Cook shellfish (oysters, clams, mussels) thoroughly.

- For shellfish in the shell, either a) boil until the shells open and continue boiling for 5 more minutes, or b) steam until the shells open and then continue cooking for 9 more minutes. Do not eat those shellfish that do not open during cooking. Boil shucked oysters at least 3 minutes, or fry them in oil at least 10 minutes at 375°F.

- Avoid cross-contamination of cooked seafood and other foods with raw seafood and juices from raw seafood.

- Eat shellfish promptly after cooking and refrigerate leftovers.

- Avoid exposure of open wounds or broken skin to warm salt or brackish water, or to raw shellfish harvested from such waters.

- Wear protective clothing (e.g., gloves) when handling raw shellfish.

And the advice from the Southern Mississippi University’s Gulf Coast Research Laboratory.