#18,474

Although the 60+ H5N1 cases reported in the United States in 2024 have all been mild, in many other parts of the world different incarnations (subtypes, clades, or genotypes) of the HPAI H5 virus have not been so benign.

- In Cambodia, we've seen 18 human H5N1 infections (clade 2.3.2.1c) reported since early 2023, with nearly a 40% fatality rate. And as we've seen previously with other incarnations of HPAI H5N1, Children and adolescents have been the hardest hit.

- While in China, more than 90 clade 2.3.4.4 H5N6 infections have been reported over the past decade (likely an undercount) with a greater than 50% fatality rate.

There may also be host differences at work; age, vaccination and previous influenza exposures, preexisting conditions, etc.

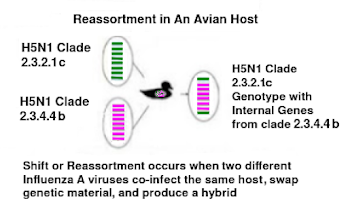

As a segmented virus with 8 largely interchangeable parts, the flu virus is like a viral LEGO (TM) set which allows for the creation of new subtypes - and within each subtype - variants called genotypes. There are already well over 100 H5N1 genotypes circulating in North America.

The waxing and waning of H5 outbreaks in places like Indonesia, Vietnam, Egypt - and even globally - over the years is largely due to the virus's continual genetic reorganization. Some of these generated variants are simply more transmissible, or more virulent, than others.

Last April, in - FAO Statement On Reassortment Between H5N1 Clade 2.3.4.4b & Clade 2.3.2.1c Viruses In Mekong Delta Region - we learned that a new genotype - made up of an older clade (2.3.2.1c) and the newer 2.3.4.4b clade of H5N1 - had emerged in Southeast Asia.

After a lull of nearly a decade, this `new' genotype appears to have sparked a resurgence of H5N1 in Southeast Asia, with reports coming from both Cambodia and Vietnam.Last May Australia reported their first H5N1 case (see Australia: Victoria Reports Imported H5N1 Case (ex India)) in a 2 year-old child who recently traveled from India. The virus was originally identified as an older H5N1 clade 2.3.2.1a virus, which is known to circulate in poultry in Bangladesh and India.

Since new genotypes can abruptly alter the behavior of a virus, they are important to monitor and analyse.

I've only reproduced the abstract and excepts from the discussion below, so follow the link to read this dispatch in its entirety. I'll have a brief postscript after the break.

DispatchYi-Mo Deng1, Michelle Wille1, Clyde Dapat, Ruopeng Xie, Olivia Lay, Heidi Peck, Andrew J. Daley, Vijaykrishna Dhanasakeran, and Ian G. BarrAbstractWe report highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) virus clade 2.3.2.1a in a child traveler returning to Australia from India. The virus was a previously unreported reassortant consisting of clade 2.3.2.1a, 2.3.4.4b, and wild bird low pathogenicity avian influenza gene segments. These findings highlight surveillance gaps in South Asia.The global panzootic of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) A(H5N1) clade 2.3.4.4b is affecting wild and domestic birds and mammals worldwide (1). This viral clade emerged after decades of evolution of goose/Guangdong (gs/Gd) lineage HPAI H5N1 viruses, first detected in geese in China in 1996 (2). Although clade 2.3.4.4b is globally dominant, a diversity of HPAI H5N1 clades are present in poultry in Asia today. Since 2005, >900 zoonotic infections have been recorded, primarily caused by contact with infected poultry (3); no evidence exists of human-to-human transmission. Reflecting the diversity of gs/Gd clades in Asia, human infections in Asia have been caused by a variety of clades. For example, Cambodia recorded 11 human infections caused by HPAI H5N1 clade 2.3.2.1c in the past 2 years, and China recorded 91 human infections caused by HPAI H5N6 and 2 cases caused by clade 2.3.4.4b H5N1 since 2014, many of them fatal.Clade 2.3.2.1a continues to be detected in South Asia, particularly in India and Bangladesh. However, human infections have been rare; to our knowledge, only 2 cases have been reported (4,5). In recent years, several poultry outbreaks of H5N1 have occurred in India (6), raising concerns about the spread and evolution of clade 2.3.2.1a HPAI H5N1 viruses. We describe HPAI H5N1 clade 2.3.2.1a infection in a traveler returning to Australia from India.The StudyA previously healthy 2.5-year-old girl returned to Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, after visiting Kolkata, India, during February 12–29, 2024. The child became ill in India; her family sought medical care on February 28. After returning to Australia, she was hospitalized on March 2, then transferred with severe influenza on March 4 and admitted to intensive care with respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation. Influenza A virus was detected by PCR, but no subtyping was performed. A 5-day course of oseltamivir was administered beginning on day 3 after admission; she recovered fully and was discharged after 2.5 weeks. No clinical illness was apparent in other family members, and no samples were taken or tested (7,8).(SNIP)

Conclusions

This report of a human HPAI H5N1 case in a traveler returning from India highlights several issues.

First, clinicians should be vigilant for serious influenza A cases in returned travelers from regions with circulating avian influenza viruses; subtyping is essential for such cases of influenza A to eliminate nonseasonal influenza infections. This step is crucial for early antiviral treatment, especially for the H5N1 and H5N6 viruses currently circulating in South/Southeast Asia, which can be serious or even fatal.

Second, although global attention is focused on the panzootic clade 2.3.4.4b viruses, a relatively small number of human infections (<100) have been recorded, and few have been serious. This contrasts with ≈100 human cases of clade 2.3.4.4 H5N6 viruses in China and clade 2.3.2.1c H5N1 in Cambodia, which caused many deaths.

Third, this case highlights the lack of H5N1 data from India. Clade 2.3.2.1a human infections in India and Nepal coincided with circulation in poultry and wild birds in Bangladesh (12). The fatal case in New Delhi in 2021, involving an 11-year-old boy who had contact with poultry (although no infected birds were reported) (4), is consistent with the genome reported here and genetically similar to H5N1 viruses present in Bangladesh. However, the patient in this study had no confirmed contact with poultry or raw poultry products; hence, the mode and route of infection cannot be determined. However, H5N1 was reported in 2023 and 2024 in Ranchi, India, 400 km from Kolkata (13,14). Since 2020, only 2 H5N1 sequences from India have been reported, compared with 314 H5N1 sequences from Bangladesh (197 in clade 2.3.2.1a) (Figure 2). Furthermore, the most recent common ancestor to A/Victoria/149/2024(H5N1) occurred almost 4 years before, highlighting the need for more sequence data from this region (Appendix Figure 2).

The complex reassortment origins of A/Victoria/149/2024(H5N1) show that clade 2.3.4.4.b viruses disseminated globally through wild birds might be transforming the genetic structure of other H5N1 clades endemic in poultry. Although HPAI H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b viruses continue to be the focus of global attention, persistent HPAI H5Nx infections in Asia should not be overlooked.

Dr. Deng heads the Genetic Analysis Unit at the WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Influenza in Australia. Her research interests encompass the genomics and evolution of human and animal influenza viruses. Dr. Wille is a senior research fellow at the Centre for Pathogen Genomics. Her primary research interest is the ecology and evolution of avian influenza viruses, in addition to other viruses found in wild birds, and more recently, entire virus communities revealed through metagenomics.

- Between 1997 and 2004, H5N1 was strictly a Southeast Asia problem.

- Between 2004 and 2012 it had expanded its range to Europe, Africa, and the Middle East

- In 2014 it diversified into H5N6 in China and as H5N8 in South Korea

- In 2014, as H5N8, it made it to North America for the first time, then vanished

- In 2016, H5N8 made it to Europe, and in 2017 it make its way into the Southern Hemisphere

- And since 2021, as H5N1 it has conquered North and South America, and made inroads into Antarctica

The only thing we can say with any certainty is the virus continues to evolve, and that its current trajectory is still on the upswing.

We ignore it at our own considerable risk.