Map showing origins & paucity of studies available for this Review

#18,796

For most of the past 120+ years, influenza A has been considered the biggest pandemic threat. It is easily spread between humans (and other mammals), it is highly mutable, it can produce severe (even fatal) illness, and it has sparked pandemics in 1918, 1957, 1968, and 2009.

In 2002-2003, an unprecedented epidemic of SARS briefly spread out of China (see SARS and Remembrance), demonstrating for the first time that a novel coronavirus might have pandemic potential.

Previously only 4 mild coronaviruses (Alpha coronaviruses 229E and NL63, and Beta coronaviruses OC43 & HKU1) - only thought capable of producing `common cold' symptoms - had been identified in humans.

While some thought SARS was a warning, others dismissed it as a fluke.

That is, until a decade later when another (more) severe coronavirus - MERS-CoV - appeared on the Arabian Peninsula, infecting thousands and killing hundreds over the past 13 years.

Relatively large (and usually nosocomial) outbreaks have been recorded (see Two MERS-CoV Hospital Super Spreading Studies) - but widespread community transmission has yet to be reported.

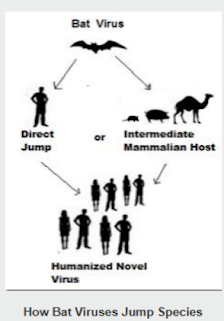

Although camels have been identified as the primary vector of MERS-CoV to humans, as with SARS-CoV, a bat reservoir host is strongly suspected.

If MERS-CoV raised concerns over the impact of coronaviruses, then SARS-CoV-2 erased all doubts. COVID produced the worst pandemic in more than 100 years; official death tolls cite 7 million COVID deaths, but estimates put it 3 to 4 times higher.

Over the past dozen years most of the research on the origins of SARS-like viruses has focused on bats.

EID Journal: A New Bat-HKU2–like Coronavirus in Swine, China, 2017

Emerg. Microbes & Infect.: Novel Coronaviruses In Least Horseshoe Bats In Southwestern China

SARS-like WIV1-CoV poised for human emergence

But in recent years we've also seen growing interest on the role played by rodents (mice & rats) and Eulipotyphla (hedgehogs, moles, shrews, etc.) in the carriage, evolution, and spread of zoonotic viruses; including novel coronaviruses.

These ubiquitous mammals are capable of hosting and spreading a wide range of pathogens, including H5N1, SARS-CoV2, and henipaviruses (see Nature: Decoding the RNA Viromes in Shrew Lungs Along the Eastern Coast of China).

Rats and mice are also capable of carrying coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2 (see mBio: SARS-CoV-2 Exposure in Norway Rats (Rattus norvegicus) from New York City). In Preprint: SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Domestic Rats After Transmission From Their Infected Owner, we saw further evidence of the susceptibility of rodents to COVID.

Just last March, in Novel Rodent Coronavirus-like Virus Detected Among Beef Cattle with Respiratory Disease in Mexico, we looked at the discovery of a novel coronavirus that most closely resembled a rodent-coronavirus first isolated in China in 2021.

All of which brings us to an excellent literature review article - published last week - which looks at research on these lesser studied hosts. Due to its length, I've only posted the link and some excerpts.

I'll have a postscript when you return.

Coronaviruses in wild rodent and eulipotyphlan small mammals: a review of diversity, ecological implications and surveillance considerationsSimon P. Jeeves1, Jonathon D. Kotwa2, David L. Pearl3, Bradley S. Pickering4,5, Jeff Bowman6,7, Samira Mubareka2,8 and Claire M. Jardine1,9

Published: 11 July 2025 https://doi.org/10.1099/jgv.0.002130

ABSTRACT

Coronaviruses are abundant and diverse RNA viruses with broad vertebrate host ranges. These viruses include agents of human seasonal respiratory illness, such as human coronaviruses OC43 and HKU1; important pathogens of livestock and domestic animals such as swine acute diarrhoea syndrome coronavirus and feline coronavirus; and human pathogens of epidemic potential such as SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2.Most coronavirus surveillance has been conducted in bat species. However, small terrestrial mammals such as rodents and eulipotyphlans are important hosts of coronaviruses as well. Although fewer studies of rodent and eulipotyphlan coronaviruses exist compared to those of bats, notable diversity of coronaviruses has been reported in the former.No literature synthesis for this area of research has been completed despite (a) growing evidence for a small mammal origin of certain human coronaviruses and (b) global abundance of small mammal species. In this review, we present an overview of the current state of coronavirus research in wild terrestrial small mammals. We conducted a literature search for studies that investigated coronaviruses infecting rodent and eulipotyphlan hosts, which returned 63 studies published up to and including 2024.We describe trends in coronavirus diversity and surveillance for these studies. To further the examination of the interrelatedness of these viruses, we conducted a phylogenetic analysis of coronavirus whole genomes recovered from rodent and eulipotyphlan hosts. We discuss important facets of terrestrial small mammal coronaviruses, including evolutionary aspects and zoonotic spillover risk. Lastly, we present important recommendations and considerations for further surveillance and viral characterization efforts in this field.

Conclusion

Research, surveillance and management of animal CoVs requires a One Health approach that considers the health of humans, wildlife, domestic animals and the ecosystems where they coexist. While research into the diversity of these viruses in bats is abundant, similar investigations in rodents and eulipotyphlans are comparatively limited.

This is particularly so in the Americas, Australia and Oceania where, despite diverse populations of wild terrestrial small mammal species, only 13.3% of the identified studies in this review were conducted (Fig. 1 and Table 1). However, in the last decade, the number of studies of CoV diversity in rodent and eulipotyphlan small mammals has been increasing.

While thorough work has been done to characterize the viruses identified, major gaps remain in understanding the ecology of these viruses in their hosts. Elucidating environmental and demographic factors involved in the reservoir ecology and sylvatic transmission of potentially zoonotic CoVs can allow steps to be taken for avoiding spillover to humans or controlling spread among animal populations [128]. Such steps include identifying target host species, environmental interfaces and sample types for further CoV surveillance.

It is clear that CoVs present a zoonotic threat. If the ecology of these viruses remains poorly understood, then novel spillover events – whether to humans or other species – will continue to be a threat.

Nature: Virome Characterization of Field-Collected Rodents in Suburban City

Viruses Review - The Hidden Threat: Rodent Borne Diseases

Experimental Infection of Rats with Influenza A Viruses: Implications for Murine Rodents in Influenza A Virus Ecology

EID Journal: Henipavirus in Northern Short-Tailed Shrew, Alabama, USA

Pathogens: Susceptibility of Synanthropic Rodents to H5N1 Subtype HPAI Viruses

Emer. Microbe & Inf.: HPAI Virus H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b in Wild Rats in Egypt during 2023