# 4417

This morning a brief, but fascinating tidbit from The Journal of Infectious Diseases where scientists have demonstrated that the H5N1 bird flu virus can replicate ex vivo in the human gut.

A hat tip to Tetano on FluTrackers for posting this item. First the abstract, then a bit of discussion.

DOI: 10.1086/651457

BRIEF REPORT

Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Viruses Can Directly Infect and Replicate in Human Gut TissuesYuelong Shu, Chris Ka‐fai Li, Zi Li, Rongbao Gao, Qian Liang, Ye Zhang, Libo Dong, Jiangfang Zhou, Jie Dong, Dayan Wang, Leying Wen, Ming Wang, Tian Bai, Dexin Li, Xiaoping Dong, Hongjie Yu, Weizhong Yang, Yu Wang,Zijian Feng, Andrew J. McMichael,3 and Xiao‐Ning Xu3

The human respiratory tract is a major site of avian influenza A(H5N1) infection. However, many humans infected with H5N1 present with gastrointestinal tract symptoms, suggesting that this may also be a target for the virus.

In this study, we demonstrated that the human gut expresses abundant avian H5N1 receptors, is readily infected ex vivo by the H5N1 virus, and produces infectious viral particles in organ culture.

An autopsy colonic sample from an H5N1infected patient showed evidence of viral antigen expression in the gut epithelium. Our results provide the first evidence, to our knowledge, that H5N1 can directly target human gut tissues.

If you’ve followed the H5N1 story closely over the past five years, then the findings of this study shouldn’t come as a complete surprise.

We’ve had more than a few hints along the way.

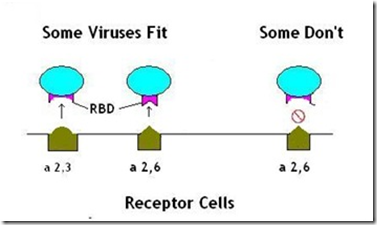

Influenza in humans (and in most mammals) is primarily seen as a respiratory disease. Human adapted influenza viruses have an affinity to bind to the α2-6 receptor cells that line the upper airway and lungs in humans.

Avian influenza viruses, however, preferentially bind to the α2-3 receptor cells that are commonly found in the gastrointestinal tract of aquatic birds, the virus’s natural host.

Influenza in birds is a mostly a gastrointestinal illness, and the virus is often spread via feces deposited in lakes and ponds.

In order for an avian flu virus, like H5N1, to successfully `jump the species barrier’ and become easily transmissible among humans, it is believed that it must adapt its RBD (receptor binding domain) to match the α2-6 receptor cells found in the more easily accessible upper respiratory system.

(Very Simplified Illustration of RBDs)

For a layman’s explanation of the science of RBDs, you might want to have a look at a couple of essays I’ve written in the past.

RBD: Looking For The Sweet Spot

Study: H1N1 Receptor Binding

Humans do have α2-3 receptor cells, however. Just not in abundance in their upper airways, where influenza viruses can most easily bind.

These α2-3 receptor cells can be found deep in the lungs and in some human epithelial tissues, although their prevalence in the human digestive tract has been a bit of an open question.

We’ve seen rare instances of human avian flu infections that were primarily gastrointestinal in nature, raising the intriguing possibility that avian viruses can replicate outside of the human respiratory system.

One of the earliest indications that H5N1 could bind and flourish in the human gastrointestinal tract comes from this study involving the deaths of a brother and sister in Vietnam in 2004.

Fatal avian influenza A (H5N1) in a child presenting with diarrhea followed by coma.

de Jong MD, Bach VC, Phan TQ, Vo MH, Tran TT, Nguyen BH, Beld M, Le TP, Truong HK, Nguyen VV, Tran TH, Do QH, Farrar J.

Oxford University Clinical Research Unit, Hospital for Tropical Diseases, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

In southern Vietnam, a four-year-old boy presented with severe diarrhea, followed by seizures, coma, and death. The cerebrospinal fluid contained 1 white cell per cubic millimeter, normal glucose levels, and increased levels of protein (0.81 g per liter).

The diagnosis of avian influenza A (H5N1) was established by isolation of the virus from cerebrospinal fluid, fecal, throat, and serum specimens. The patient's nine-year-old sister had died from a similar syndrome two weeks earlier. In both siblings, the clinical diagnosis was acute encephalitis.

Neither patient had respiratory symptoms at presentation. These cases suggest that the spectrum of influenza H5N1 is wider than previously thought.

In June of 2007, we got a report (see Atypical Presentations of H5N1) out of Indonesia, of a child infected with H5N1 but that presented without respiratory symptoms.

A year later, in a large review of Chinese bird flu patients (see Clinical Case Review Of 26 Chinese H5N1 Patients), we find several mentions of gastrointestinal involvement as well.

Diarrhea was present in only two H5N1 cases at admission, but developed in a quarter of cases during hospitalization. Diarrhea was a common presenting symptom among H5N1 cases in Vietnam [11], [12] and Thailand [13], but was reported infrequently among cases in Hong Kong SAR, China [9], [10], and Indonesia [4], [16].

H5N1 virus and viral RNA have been detected in feces and intestines of human H5N1 cases [12], [17], [30], [33]. Whether the gastrointestinal tract is a primary site for H5N1 virus infection is currently unknown.

And even novel H1N1 (and perhaps Influenza B) are being looked at for exhibiting unusual gastrointestinal symptoms. Last January, in Influenza’s Gastrointestinal Connection, I wrote about a study that appeared in BMC Infectious Diseases.

Influenza virus infection among pediatric patients reporting diarrhea and influenza-like illness

The detection of influenza viral RNA and viable influenza virus from stool suggests that influenza virus may be localized in the gastrointestinal tract of children, may be associated with pediatric diarrhea and may serve as a potential mode of transmission during seasonal and epidemic influenza outbreaks.

And for my final exhibit, in the CDC’s Interim guidance on Infection Control for the pandemic H1N1 Virus, they state:

Transmission of influenza through the air over longer distances, such as from one patient room to another, is thought not to occur. All respiratory secretions and bodily fluids, including diarrheal stools, of patients with 2009 H1N1 influenza are considered to be potentially infectious.

With today’s study, another piece has been added to the influenza jigsaw puzzle. One that may help answer a nagging question about the atypical presentation of influenza infections.