# 4518

When we think about infectious diseases we are apt to think first about viral or bacterial infections. But fungal Infections, or mycoses, can cause serious illness or injury as well.

When I moved to Arizona in 1975 to work as a paramedic, one of the first things I learned about was Coccidioidomycosis, also known as Valley Fever, which is endemic in our southwestern states and much of northern Mexico.

The illness is caused by the inhalation of one of two soil borne fungi, Coccidioides immitis or C. posadasii., that become airborne when the earth is disturbed by farming, construction, or windstorms.

Most of the people who live in these areas have been exposed and inoculated with the spores, and either developed brief silent or sub-clinical infections, or perhaps experienced mild flu-like symptoms.

Severe disease – although rare – can occur. Sometimes even years after initial exposure.

In 2001, Arizona alone reported more than 2200 cases of Coccidioidomycosis (MMWR 52(06);109-112).

Another mycotic disease called Histoplasmosis is found in the Ohio River Valley, and along the lower Mississippi river, and it too can cause severe disease in rare instances.

In the case of Histoplasmosis, the causative agent is Histoplasma capsulatum, which is found in bird and bat droppings. These can become airborne when these droppings dry out and are picked up by the wind.

Neither of these diseases are communicable. They are acquired from the environment. They are not transmitted from one person to another.

Those with weakened immune systems are generally most at risk of seeing serious complications from these fungal infections, although even healthy people are occasionally stricken.

I mention these two endemic fungal diseases so as to help put the following report into perspective.

Over the past 10 years, a new fungal threat has emerged in the Pacific Northwest. Cryptococcus gattii, a tropical fungus common in Australia and New Guinea, showed up unexpectedly on Vancouver Island in 1999 – eventually infecting more than 200 people.

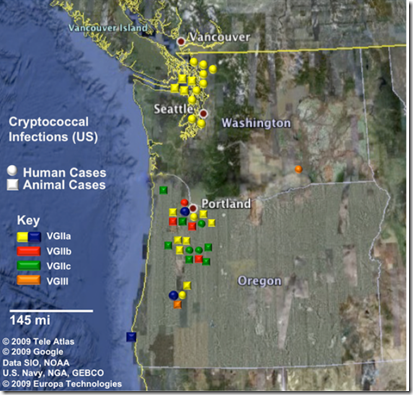

Since then, the fungus has expanded its range, appearing in British Columbia, Washington, and Oregon. Of particular concern, a more pathogenic strain – one that apparently infects healthy individuals and has a higher mortality rate, has recently been identified.

This fungus – a yeast really – is found in a number of species of trees (primarily Douglas fir & Western hemlock) and in the soil. It can be spread by the wind, particularly during the warmer summer months.

This fungus has a wide host range, having been found to infect humans along with cats, dogs, porpoises, ferrets, llamas, elk, alpacas, and sheep.

While all of this sounds dire, one must remember that hundreds of thousands of people in the Pacific Northwest have likely been exposed to these airborne spores over the past 10 years.

So far, only about 250 people in the region have developed identifiable illness during that time. As a broad-based public health hazard, for now at least, this ranks fairly low.

For epidemiologists, environmental scientists, and mycologists, however . . . this is fascinating stuff indeed.

We’ll start off with the Reuters story, which provides a brief overview:

Potentially deadly fungus spreading in US, Canada

22 Apr 2010 22:21:58 GMT

Source: Reuters

* Fungus is unique genetic strain

* Climate change may aid its spread

WASHINGTON, April 22 (Reuters) - A potentially deadly strain of fungus is spreading among animals and people in the northwestern United States and the Canadian province of British Columbia, researchers reported on Thursday.

The airborne fungus, called Cryptococcus gattii, usually only infects transplant and AIDS patients and people with otherwise compromised immune systems, but the new strain is genetically different, the researchers said.

"This novel fungus is worrisome because it appears to be a threat to otherwise healthy people," said Edmond Byrnes of Duke University in North Carolina, who led the study.

For the hard core science geek details on this emerging pathogen you may wish to read the complete study published in PLoS Pathogens.

Fair warning, while fascinating, this isn’t `light reading’.

I’ve reproduced the author’s summary (reparagraphed for readability) below.

Emergence and Pathogenicity of Highly Virulent Cryptococcus gattii Genotypes in the Northwest United States

: Byrnes EJ III, Li W, Lewit Y, Ma H, Voelz K, et al. (2010) Emergence and Pathogenicity of Highly Virulent Cryptococcus gattii Genotypes in the Northwest United States. PLoS Pathog 6(4): e1000850. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000850

Emerging and reemerging infectious diseases are increasing worldwide and represent a major public health concern. One class of emerging human and animal diseases is caused by fungi.

In this study, we examine the expansion on an outbreak of a fungus, Cryptococcus gattii, in the Pacific Northwest of the United States. This fungus has been considered a tropical fungus, but emerged to cause an outbreak in the temperate climes of Vancouver Island in 1999 that is now causing disease in humans and animals in the United States.

In this study we applied a method of sequence bar-coding to determine how the isolates causing disease are related to those on Vancouver Island and elsewhere globally.

We also expand on the discovery of a new pathogenic strain recently identified only in Oregon and show that it is highly virulent in immune cell and whole animal virulence experiments. These studies extend our understanding of how diseases emerge in new climates and how they adapt to these regions to cause disease.

Our findings suggest further expansion into neighboring regions is likely to occur and aim to increase disease awareness in the region.

A couple of months ago the CDC’s Journal of Emerging Infectious Diseases published a research article on the epidemiology of the spread of C. gattii in British Columbia.

Volume 16, Number 2–February 2010

Research

Epidemiology of Cryptococcus gattii, British Columbia, Canada, 1999–2007

Eleni Galanis

and Laura MacDougall

Author affiliations: British Columbia Centre for Disease Control, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada (E. Galanis, L. MacDougall); and University of British Columbia, Vancouver (E. Galanis)

Abstract

British Columbia, Canada, has the largest reported population of Cryptococcus gattii–infected persons worldwide. To assess the impact of illness, we retrospectively analyzed demographic and clinical features of reported cases, hospitalizations, and deaths during 1999–2007.

A total of 218 cases were reported (average annual incidence 5.8 per million persons). Most persons who sought treatment had respiratory illness (76.6%) or lung cryptococcoma (75.4%). Persons without HIV/AIDS hospitalized with cryptococcosis were more likely than those with HIV/AIDS to be older and admitted for pulmonary cryptococcosis.

The 19 (8.7%) persons who died were more likely to be older and to have central nervous system disease and infection from the VGIIb strain. Although incidence in British Columbia is high, the predominant strain (VGIIa) does not seem to cause greater illness or death than do other strains.

Further studies are needed to explain host and strain characteristics for regional differences in populations affected and disease outcomes.