# 4860

Arkanoid Legent has a story this morning from the Asahi Shimbun in Japan with this attention getting headline:

Mutated avian flu can infect humans

BY YURI OIWA THE ASAHI SHIMBUN

A strain of highly pathogenic avian influenza (H5N1) that mutated in pigs in Indonesia has acquired the ability to infect humans, researchers have found.

If all of this sounds a bit familiar, it may be because I wrote about this study at some length in mid-August (see EID Journal: Asymptomatic H5N1 In Pigs).

While obviously an important piece of field research - one that illustrates why we need to do a much better job of surveillance of pigs (and other mammals) for emerging viruses – the headline and lede may be just a tad overstated.

Since this story is likely to get a good deal of play over the next few days, a revisiting of the original study seems in order.

First, the setup for the research via some excerpts (slightly reformatted for readability) from the EID Journal abstract . . . then some discussion.

DOI: 10.3201/eid1610.100508

Nidom CA, Takano R, Yamada S, Sakai-Tagawa Y, Daulay S, Aswadi, D, et al. Influenza A (H5N1) viruses from pigs, Indonesia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010 Oct;[Epub ahead of print]

Influenza A (H5N1) Viruses from Pigs, Indonesia

Pigs have long been considered potential intermediate hosts in which avian influenza viruses can adapt to humans. To determine whether this potential exists for pigs in Indonesia, we conducted surveillance during 2005–2009.

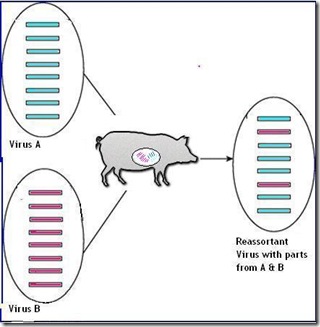

Pigs have long been suspected as being ideal `mixing vessels’ for influenza because they possess both avian-like (SAα2,3Gal) and human-like (SAα2,6Gal) receptor cells in their respiratory tract.

That means pigs are susceptible to human, swine, and avian strains of flu. And they are capable of being infected by more than one flu virus at a time.

This opens the possibility for two flu viruses to swap genetic material inside a pig, and create a hybrid (reassortant) strain as depicted in the illustration below (other hosts can cause reassortments, too).

This is essentially how the 2009 H1N1 pandemic virus was born, although it took multiple gene swaps over a period of years before it emerged into the human population.

The highlights of this latest study were:

Researchers found that during the period of 2005-2007 that 7.4% of pigs surveyed in Indonesia carried the H5N1 virus.

Phylogenic analysis showed at least 3 separate introductions into the pig population.

More recent surveillance (2008-2009) did not turn up any active infections, but 1% of pigs tested carried antibodies to the H5N1 virus.

The pigs were asymptomatic, but the evidence points to ongoing transmission within the pig population.

In one sample researchers found an adaptation of the virus to human-like receptor cells via an Ala134Ser mutation (swaping alanine with serine) at position 134.

The last point is obviously a concern.

But just as obviously, if only one instance was detected – and that was at least 3 years ago – then that particular mutation isn’t exactly thriving in Indonesia’s pig population.

The point is . . . if it happened once, it could obviously happen again.

And the next time, the reassorted virus could be more biologically `fit’, and start efficiently spreading to other pigs, and eventually perhaps to humans.

Which is why surveillance of farm animals (particularly, but not exclusively, pigs) is so important.

And not just in Indonesia.

Despite the danger posed by emerging viruses there is considerable reluctance to testing herds of swine, both here in the US, and around the world.

Pig owners fear negative publicity, or a culling of their herds, should anything be found. And of course, surveillance costs money.

`Swine flu’ proved to be an expensive public relations nightmare for the pork industry, and so pig farmers are understandably wary.

As the authors point out, the asymptomatic carrying of these viruses is of particular concern. There are no outward signs to alert a farmer than their herd is sick.

This could lead to infected pigs being transported to new areas, or intermingled with uninfected swine, spreading a new virus further.

The important point to this story is not so much the one human-adapted virus they discovered in 2007, but what we need to be looking for today.

And in far too many places around the world, simply are not.