# 5631

Even before the novel H1N1 virus emerged in the Spring of 2009, pregnancy was considered to be a significant risk factor during an influenza pandemic.

Researchers knew that during the 1918 pandemic an abnormally high number of pregnant women died from the the Spanish Flu, and those that survived endured a very high miscarriage rate.

Even during the much milder 1957 Asian Flu, pregnant women reportedly suffered disproportionately higher mortality rates than non-pregnant women of the same age.

The following anecdotal reports come from a 2008 CDC EID Journal article:

Rasmussen SA, Jamieson DJ, Bresee JS. Pandemic influenza and pregnant women. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet].

Among 1,350 reported cases of influenza among pregnant women during the pandemic of 1918, the proportion of deaths was reported to be 27% (5).

Similarly, among a small case series of 86 pregnant women hospitalized in Chicago for influenza in 1918, 45% died (6).

Among pregnancy-associated deaths in Minnesota during the 1957 pandemic, influenza was the leading cause of death, accounting for nearly 20% of deaths associated with pregnancy during the pandemic period; half of women of reproductive age who died were pregnant (7).

Pregnant women also appear to be more susceptible to influenza than non-pregnant women, although the exact reasons for this aren't well understood.

It is believed, however, that the normal protections of a woman's immune system are temporarily altered to allow her to carry what is essentially a foreign body- a fetus - without rejection.

And that alteration can place the mother (and child) at greater risk of infection from the influenza virus.

Which is why the CDC and many other public health agencies strongly encourage pregnant women to get vaccinated against both seasonal and pandemic influenza.

Very early into the 2009 H1N1 outbreak – even before the declaration of a pandemic by the World Health Organization – it became apparent that pregnant women were making up a disproportionate number of ICU admissions for influenza.

On May 1st of 2009, a little more than a week after the first cases of novel H1N1 began to make headlines, the CDC published new guidelines for pregnant women in the Health Care or Education field that might come in direct contact with the Swine flu virus (See CDC Guidelines On Pregnancy And Pandemic Flu).

Two weeks after that the MMWR published case studies of three pregnant women who had contracted novel H1N1.

Throughout the summer, pregnancy and flu was a major topic by public health officials around the world, with the WHO issuing a Pandemic Briefing # 5: Influenza In Pregnant Women in late July of 2009.

Since then, we’ve seen a number of studies on the impact of the H1N1 virus on pregnant women, including BMJ Study: Pregnancy & Flu – published in the spring of 2010.

Although it was widely reported (see Pregnancy & Flu: A Bad Combination) during 2009 that pregnant women were up to 6 times more likely to be hospitalized with influenza than were non-pregnant women, this study found the risks of influenza death among pregnant women to be actually higher.

Less well quantified has been the health impact on the unborn child when the mother was hospitalized with H1N1 influenza.

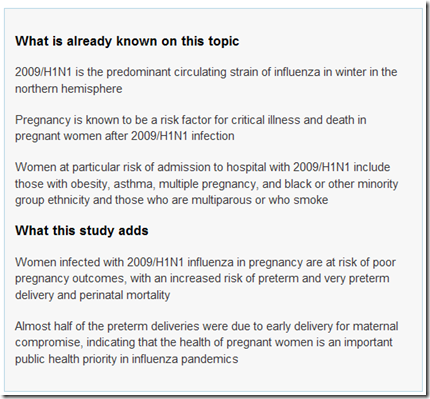

Today an open access research article in the BMJ that found that pregnant women who were admitted to the hospital with an H1N1 infection experienced a 3 to 4 times higher rate of preterm birth, 4 to 5 times greater risk of stillbirth, and a 4 to 6 times higher rate of neonatal death.

Perinatal outcomes after maternal 2009/H1N1 infection: national cohort study

Matthias Pierce, Jennifer J Kurinczuk, Patsy Spark, Peter Brocklehurst, Marian Knight,

Accepted 13 April 2011

Abstract

Objectives To follow up a UK national cohort of women admitted to hospital with confirmed 2009/H1N1 influenza in pregnancy in order to obtain a complete picture of pregnancy outcomes and estimate the risks of adverse fetal and infant outcomes.

Participants 256 women admitted to hospital with confirmed 2009/H1N1 in pregnancy during the second wave of pandemic infection between September 2009 and January 2010; 1220 pregnant women for comparison.

Main outcome measures Rates of stillbirth, perinatal mortality, and neonatal mortality; odds ratios for infected versus comparison women.

Results Perinatal mortality was higher in infants born to infected women (10 deaths among 256 infants; rate 39 (95% confidence interval 19 to 71) per 1000 total births) than in infants of uninfected women (9 deaths among 1233 infants; rate 7 (3 to 13) per 1000 total births) (P<0.001).

This was principally explained by an increase in the rate of stillbirth (27 per 1000 total births v 6 per 1000 total births; P=0.001). Infants of infected women were also more likely to be born prematurely than were infants of comparison women (adjusted odds ratio 4.0, 95% confidence interval 2.7 to 5.9).

Infected women who delivered preterm were more likely to be infected in their third trimester (P=0.046), to have been admitted to an intensive care unit (P<0.001), and to have a secondary pneumonia (P=0.001) than were those who delivered at term.

Conclusions This study suggests an increase in the risk of poor outcomes of pregnancy in women infected with 2009/H1N1, which reinforces the message from studies of maternal risk alone. The health of pregnant women is an important public health priority in future waves of this and other influenza pandemics.

The bottom line is that influenza presents a serious health threat to the mother, and to the child she carries.

While flu vaccines are very safe, and most years reasonably effective, many pregnant women avoid taking one out of fears they may experience a rare adverse reaction.

Today’s study highlights the fact that when you are dealing influenza and pregnancy, simply doing nothing represents a serious health risk of its own.

Risks that could be substantially reduced by vaccination.