Coronavirus – Credit CDC PHIL

# 6958

Yesterday the journal Eurosurveillance published a report on the numerous contacts of a patient from Qatar who last fall was treated for several weeks at a German lung clinic before being diagnosed as infected with the novel coronavirus (NCoV).

During this time scores of hospital personnel were potentially exposed. Despite taking few protective measures, none of these contacts appear to have become infected.

What makes this case a bit unique is the timing of this patient’s transfer to Germany, some 23 days after his symptoms first appeared.

While it is always perilous to base conclusions with such a limited dataset, this lack of secondary transmission late in the patient’s illness suggests a limit on the infectious period of a patient infected with NCoV.

Additionally, this patient’s interview turned up a possible zoonotic source of his viral infection.

It’s a long and detailed report, very much worth reading in its entirety. Below are the the link, abstract and some excerpts (slightly reformatted for readability), after which I’ll be back with more.

U Buchholz , M A Müller, A Nitsche, A Sanewski, N Wevering, T Bauer-Balci, F Bonin, C Drosten, B Schweiger, T Wolff, D Muth, B Meyer, S Buda, G Krause, L Schaade, W Haas

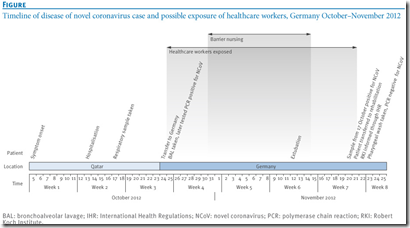

24 October 2012, a patient with acute respiratory distress syndrome of unknown origin and symptom onset on 5 October was transferred from Qatar to a specialist lung clinic in Germany.

Late diagnosis on 20 November of an infection with the novel Coronavirus (NCoV) resulted in potential exposure of a considerable number of healthcare workers.

Using a questionnaire we asked 123 identified contacts (120 hospital and three out-of-hospital contacts) about exposure to the patient. Eighty-five contacts provided blood for a serological test using a two-stage approach with an initial immunofluorescence assay as screening test, followed by recombinant immunofluorescence assays and a NCoV-specific serum neutralisation test.

Of 123 identified contacts nine had performed aerosol-generating procedures within the third or fourth week of illness, using personal protective equipment rarely or never, and two of these developed acute respiratory illness. Serology was negative for all nine. Further 76 hospital contacts also tested negative, including two sera initially reactive in the screening test.

The contact investigation ruled out transmission to contacts after illness day 20. Our two-stage approach for serological testing may be used as a template for similar situations.

<SNIP>

Patient interview

The patient reported to live in Doha, Qatar. He used to be a heavy smoker (2 to 3 packs of cigarettes per day), but denied smoking waterpipe or chewing qat.

Disease onset was rapid, with initial symptoms including fever (40 °C), cough, runny nose, and shortness of breath. Subjective weakness was pronounced. After the first two days of illness he improved a little but deteriorated again, and was finally admitted to hospital on day eight of illness because of increasing dyspnoea.

He reported no subjective symptoms of renal impairment such as foamy urine, reduced urine output, or back pain. He had not travelled and had no known contact with any other reported cases of NCoV infection.

The patient owned a camel and goat farm and reported a large number of casual contacts (approx. 50 persons per day) on a regular basis. He remembered that before his disease onset some goats were ill and had fever. He did not have direct contact with the goats or any other animals especially falcons or bats, but said he had eaten goat meat.

He also reported to have had contact with one of his animal caretakers who was ill with severe cough and was hospitalised. Other than the animal caretaker, he did not remember persons with severe respiratory illnesses in his wider or closer social environment.

We know the infectious period of viral diseases can vary widely, and is often dependent upon the age and the individual immune response of the host. Those with compromised immune systems often shed a virus longer than those with a more robust immune system.

The CDC’s general take on influenza’s infectivity is:

Most healthy adults may be able to infect others beginning 1 day before symptoms develop and up to 5 to 7 days after becoming sick. Children may pass the virus for longer than 7 days. Symptoms start 1 to 4 days after the virus enters the body. That means that you may be able to pass on the flu to someone else before you know you are sick, as well as while you are sick. Some persons can be infected with the flu virus but have no symptoms. During this time, those persons may still spread the virus to others.

Norovirus, on the other hand, is most contagious during the first 72 hours of infection, but patients can still shed the virus in their stool for up to 2-weeks (see the CDC’s Clinical Overview)

With the caveat that while this emerging NCoV is a coronavirus - it is not SARS - in 2003 researchers found (unlike with influenza), those infected with the SARS virus did not appear to be contagious prior to developing symptoms.

The CDC’s SARS FAQ reads:

How long is a person with SARS infectious to others?

Available information suggests that persons with SARS are most likely to be contagious only when they have symptoms, such as fever or cough. Patients are most contagious during the second week of illness. However, as a precaution against spreading the disease, CDC recommends that persons with SARS limit their interactions outside the home (for example, by not going to work or to school) until 10 days after their fever has gone away and their respiratory (breathing) symptoms have gotten better.

This lack of asymptomatic (or presymptomatic) transmission of SARS virus made it easier to identify those infected, and made it possible to contain that outbreak.

In 2004 an EID Journal dispatch looked at how long the SARS coronavirus could be detected in a patient’s sputum and stool.

Long-term SARS Coronavirus Excretion from Patient Cohort, China

Wei Liu, Fang Tang, Arnaud Fontanet, Lin Zhan, Qiu-Min Zhao, Pan-He Zhang, Xiao-Ming Wu, Shu-Qing Zuo, Laurence Baril, Astrid Vabret, Zhong-Tao Xin, Yi-Ming Shao, Hong Yang, and Wu-Chun Cao

Abstract

This study investigated the long-term excretion of severe acute respiratory syndrome–associated coronavirus in sputum and stool specimens from 56 infected patients. The median (range) duration of virus excretion in sputa and stools was 21 (14–52) and 27 (16–126) days, respectively. Coexisting illness or conditions were associated with longer viral excretion in stools.

It should be noted that shedding enough virus to be detectable by today’s modern RT-PCR testing or virus culture, and being contagious and able to spread the virus, may be two entirely different propositions.

With just over a dozen laboratory confirmed cases of NCoV infection, we are still very early in the learning curve of this emerging virus.

A limited contagious period is hardly unexpected, but this study does provide an important data point. We’ll need a larger sample size before researchers can quantify the typical infectious period for this virus.

The other intriguing aspect of this study is the possible (albeit, tenuous) link to goats as a zoonotic source of the virus.

As the authors point out in their discussion (see below), this isn’t the first time that farm animal exposure has been mentioned in conjunction with NCoV.

During two interviews that the patient kindly agreed to, we explored a wide spectrum of factors that he might have been exposed to. Even though NCoV is genetically similar to bat coronaviruses [1,13,14], other animals may serve as (intermediate) host as well.

While our patient denied contact to bats, he remembered ill goats among the animals on his farm. Albarrak et al. reported that the first Saudi case was exposed to farm animals, but the first Qatari patient and the second Saudi patient were not [15]. Although our patient reported no direct contact with his animals, one animal caretaker working for him was ill with cough and might have been an intermediate link in the chain of infection.

Coronaviruses do infect ruminants such as goats [16] and thus goats could be considered as a possible source of origin for the novel virus, particularly in the geographical and cultural context of our patient.

So far, the number of known cases remains very small. Whether this virus has what it takes to present a larger public health concern has yet to be determined.

With scientists, doctors, and disease detectives hot on its trail, I fully expect we’ll know a good deal more about this emerging virus a month or two from now.

Stay tuned.