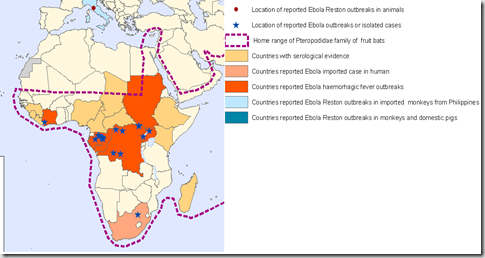

Range of Reported Ebola Outbreaks 1976-2014 – Credit WHO

# 8394

Nearly 10 days ago FluTrackers began to compile and translate a series of vague reports out of the West African nation of Guinea of an unidentified hemorrhagic fever. Early media reports speculated on Lassa fever as a potential cause. Last week Crof at Crofsblog began to cover these reports as well (see Guinea: Unknown disease evokes Ebola and yellow fever).

Yesterday, with the death toll approaching 60, it was widely reported that this outbreak was due to one of the Ebola virus strains (see Crof’s coverage here, here, and here).

Overnight ProMed Mail published a statement from the National Reference Center for Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers - Institut Pasteur in Lyon, France (see EBOLA VIRUS DISEASE - WEST AFRICA: GUINEA, ZAIRE EBOLAVIRUS SUSPECT) where testing of samples is ongoing, and they report a `strong homology to Zaire Ebolavirus’, considered to be the deadliest strain.

Ebola was first discovered in Zaire and Sudan in 1976 and since then has become almost legendary for its incredibly high fatality rate and gruesome hemorrhagic symptoms.

As a public health threat, Ebola – which has been blamed for fewer than 2,000 deaths over the past 30+ years - pales in comparison to most of the world’s less feared infectious diseases. Simple childhood pneumonia, claims 1.8 million lives each year (cite) and Malaria claims between one half, to one million lives a year (cite).

Despite its rarity, movies like 1995’s Outbreak with Dustin Hoffman, and books like Tom Clancy’s Executive Orders and The Hot Zone by Richard Preston, have helped to turn Ebola into the ultimate nightmare disease in the eyes of the public.

Fortunately, the spread of these African Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers (VHFs which includes Ebola, Marburg & Lassa) has thus far been geographically limited. The illness strikes quickly, with profound and debilitating symptoms, and that helps to limit human-to-human spread.

But as Maryn Mckenna pointed out in her 2010 blog Lassa fever: Coming to an airport near you, with our increasingly mobile population, opportunities for exotic tropical diseases like VHF to hop on an airplane and arrive in any major city in the world are increasing.

While the zoonotic reservoir for the Ebola virus has yet to be firmly established, bats are considered to be the most likely candidate.

In 2012 NIAID produced the following short (3 minute) video on Ebola, and the research ongoing in the Congo to determine its source, which also makes a good primer on the disease.

There are currently five known strains of the disease, of which four are highly pathogenic in humans.

Ebola Zaire, with a mortality rate approaching 90%, is considered to be the deadliest strain, followed by Ebola Sudan (50%-70% fatal). Taï Forest virus (formerly Côte d’Ivoire ebolavirus) and Bundibugyo ebolavirus (BEBOV) are less well studied, but appear to have lower mortality rates.

With no vaccine, and no effective treatment, the primary public health focus during an outbreak is breaking the chain of transmission. The following comes from the CDC’s Ebola webpage.

The prevention of Ebola HF presents many challenges. Because it is still unknown how exactly people are infected with Ebola HF, there are few established primary prevention measures.

When cases of the disease do appear, there is increased risk of transmission within health care settings. Therefore, health care workers must be able to recognize a case of Ebola HF and be ready to employ practical viral hemorrhagic fever isolation precautions or barrier nursing techniques. They should also have the capability to request diagnostic tests or prepare samples for shipping and testing elsewhere.

MSF (Médecins Sans Frontières) health staff in protective clothing constructing perimeter for isolation ward.

Barrier nursing techniques include:

- wearing of protective clothing (such as masks, gloves, gowns, and goggles)

- the use of infection-control measures (such as complete equipment sterilization and routine use of disinfectant)

- isolation of Ebola HF patients from contact with unprotected persons.

The aim of all of these techniques is to avoid contact with the blood or secretions of an infected patient. If a patient with Ebola HF dies, it is equally important that direct contact with the body of the deceased patient be prevented.

CDC, in conjunction with the World Health Organization, has developed a set of guidelines to help prevent and control the spread of Ebola HF. Entitled Infection Control for Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers In the African Health Care Setting [PDF - 2MB], the manual describes how to:

- recognize cases of viral hemorrhagic fever (such as Ebola HF)

- prevent further transmission in health care setting by using locally available materials and minimal financial resources.

A listing of known outbreaks over the past 38 years can be found at:

Chronology of Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever Outbreaks

The odd virus out - Ebola Reston - which can infect and kill non-human primates, has not been shown to produce disease in man (it has been shown to produce serious illness in pigs, however). Ebola Reston is also the only Ebola virus known to be endemic outside of Africa.

Ebola Reston was first discovered in crab-eating macaques, imported from the Philippines, at a research laboratory in Reston, Virginia (USA) (hence the name) in 1989. This discovery was recounted in the book, The Hot Zone, by Richard Preston.

Since pigs and humans share many commonalities in their physiology (if that induces discomfiture in you, think how the pig feels) any disease that jumps to (and causes illness) in swine is of concern to scientists.

While humans can be infected by the this non-lethal strain (3 researchers in Reston developed high antibody titers to the virus), it has not been shown to cause human illness. In 2009, the World Health Organization reported the following on Ebola Reston infections in humans and pigs in the Philippines.

Ebola Reston in pigs and humans in the Philippines

3 February 2009 - On 23 January 2009, the Government of the Philippines announced that a person thought to have come in contact with sick pigs had tested positive for Ebola Reston Virus (ERV) antibodies (IgG). On 30 January 2009 the Government announced that a further four individuals had been found positive for ERV antibodies: two farm workers in Bulacan and one farm worker in Pangasinan - the two farms currently under quarantine in northern Luzon because of ERV infection was found in pigs - and one butcher from a slaughterhouse in Pangasinan. The person announced on 23 January to have tested positive for ERV antibodies is reported to be a backyard pig farmer from Valenzuela City - a neighbourhood within Metro Manila.

The good news is, none of the human cases developed signs of illness.

The caveat is, that viruses can, and do, mutate over time. And we have no idea what changes would be needed to turn Ebola Reston into a pathogenic virus for humans.

For more on the hunt for emerging viruses from the jungles and forests of Africa, you may wish to revisit these blogs: