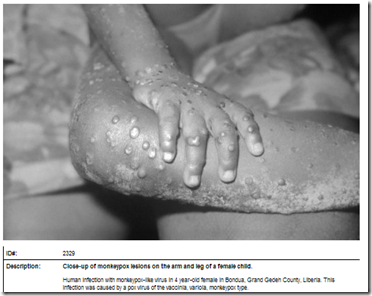

Monkeypox – Credit CDC PHIL

# 8769

There are reports this weekend of a possible outbreak of monkeypox in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (see ProMed Mail report). Reportedly 12 people have been infected, and two have died. While monkeypox is suspected, we won’t have a definitive answer until laboratory test results are released.

Human monkeypox was first identified in 1970 in the DRC, and since then has sparked mostly small, spoardic outbreaks in the Congo Basin and Western Africa.

But in 1996-97, a major outbreak occurred in the Democratic Republic of Congo (see Eurosurveillance Report), where more than 500 cases in the Katako-Kombe and Lodja zones were identified. Mortality rates were lower for this outbreak (1.5%) than earlier ones, but this was the biggest, and longest duration outbreak on record.

The name `monkeypox’ is a bit of a misnomer. It was first detected (in 1958) in laboratory monkeys, but further research has revealed its host to be rodents or possibly squirrels. Humans can contract it in the wild from an animal bite or direct contact with the infected animal’s blood, body fluids, or lesions.

Consumption of undercooked bushmeat is also suspected as infection risk, but human-to-human transmission is also possible. This from the CDC’s Factsheet on Monkeypox:

The disease also can be spread from person to person, but it is much less infectious than smallpox. The virus is thought to be transmitted by large respiratory droplets during direct and prolonged face-to-face contact. In addition, monkeypox can be spread by direct contact with body fluids of an infected person or with virus-contaminated objects, such as bedding or clothing.

While we talk often about the risks of infected individuals boarding planes and flying anywhere in the world (see The Global Reach Of Infectious Disease), human carriers aren’t the only concern.

A little over a decade ago – at roughly the same time as the global SARS outbreak was winding down – the United States experienced an unprecedented outbreak of Monkeypox - when an animal distributor imported hundreds of small animals from Ghana, which in turn infected prairie dogs that were subsequently sold to the public (see 2003 MMWR Multistate Outbreak of Monkeypox --- Illinois, Indiana, and Wisconsin, 2003).

By the time this outbreak was quashed, the U.S. saw 37 confirmed, 12 probable, and 22 suspected human cases. Among the confirmed cases 5 were categorized as being severely ill, while 9 were hospitalized for > 48 hrs; although no patients died (cite).

The CDC describes the signs and symptoms of monkeypox as being ` similar to those of smallpox, but usually milder. . . In Africa, monkeypox is fatal in as many as 10% of people who get the disease; the case fatality ratio for smallpox was about 30% before the disease was eradicated.’

As it turns out, there are at least two strains of the monkeypox virus (see Virulence differences between monkeypox virus isolates from West Africa and the Congo basin), with the West African variety being less virulent, and less transmissible, than the Central African strain.

And in 2003, we got lucky. The imported strain was the West African variety, which no doubt lessened its impact.

The trade in exotic pets (whether legal or illegal), and in (often illegal) `bush meat’, provides an easy avenue for the cross-border introduction of zoonotic diseases around the globe. Monkeypox is just one of many possible pathogenic passengers.

And despite heightened airport security around the world, more contraband gets through than most people think.

- A year ago, in All Too Frequent Flyers, we saw a Vietnamese passenger, on a flight into Dulles Airport, who was caught with 20 raw Chinese Silkie Chickens in his (carrion) luggage.

- A month later, in Vienna: 5 Smuggled Birds Now Reported Positive For H5N1, we saw a couple arrested for trying to smuggle 60 birds in from Bali.

- In May of 2013, UK customs agents in Leeds twice intercepted hidden caches of live grey francolin birds being brought in from Islamabad (see Daily Mail story Customs officers find live Asian fighting birds in suitcases after smugglers flew them into Britain).

- In 2012, in Taiwan Seizes H5N1 Infected Birds, we learned of a smuggler who was detained at Taoyuan international airport in Taiwan after arriving from Macau dozesns of infected birds. Nine people exposed to these birds were observed for 10 days, and luckily none showed signs of infection.

- Also in 2012, in Psittacosis Identified In Hong Kong Respiratory Outbreak, we saw a limited outbreak among personnel at an agricultural station where smuggled birds seized by customs agents had been quarantined. Subsequently 3 parrots died, and 10 were euthanized.

- And in 2010, two men were indicted for brazenly attempting to smuggle dozens of song birds (strapped to their legs inside their pants) into LAX from Vietnam (see Man who smuggled live birds strapped to legs faces 20 years in prison).

While these are stories of successful interdiction, we shouldn’t be too comforted, as they appear to represent a small percentage of the illicit trade. Three years ago British papers were filled with reports of `bushmeat’ being sold in the UK. A couple of links to articles include:

Meat from chimpanzees 'is on sale in Britain' in lucrative black market

Chimp meat discovered on menu in Midlands restaurants

The slaughtering of these intelligent primates for food (but mostly profit) is horrific its own right, but it also has the very real potential of introducing zoonotic pathogens to humans.

While most people think of bushmeat hunting as something that a few indigenous tribes in Africa might do to feed their protein-starved communities, the reality is that hundreds of tons of bushmeat are butchered and exported (usually smuggled) to Europe, Asia, and North America every year.

In the summer of 2010 headlines were made when a study – published in the journal Conservation Letters looked at the amount of smuggled bushmeat (414 lbs) that was seized coming into Paris's Charles de Gaulle airport over a 17 day period on flights from west and central Africa.

Researchers estimated that about five tons of bushmeat gets into Paris each week (cite AP article).

Experts were not able to identify all of the bushmeat seized, but among the species they could ID, they found monkeys, large rats, crocodiles, small antelopes and pangolins (anteaters). Sobering when you consider the current outbreak of Ebola in Western Africa likely began with the killing, butchering, and consumption of infected bushmeat.

In 2005, the CDC’s EID Journal carried a perspective article on the dangers of bushmeat hunting by Nathan D. Wolfe, Peter Daszak, A. Marm Kilpatrick, and Donald S. Burke; Bushmeat Hunting, Deforestation, and Prediction of Zoonotic Disease.

It describes how it may take multiple introductions of a zoonotic pathogen to man – over a period of years or decades – before it adapts well enough to human physiology to support human-to-human transmission.

It has been estimated that as much as three-quarters of human diseases originated in other animal species, and there are undoubtedly more out there, waiting for an opportunity to jump to a new host. Sadly, the role of `wild flavor’ cuisine in SARS epidemic in China and the introduction of HIV to humans via the hunting of bushmeat in Africa, are lessons we have yet to fully embrace.

On the frontlines attempting to interdict the next emerging pathogen is the above mentioned Dr. Nathan Wolfe, whom I’ve written about several times before, including:

Nathan Wolfe And The Doomsday Strain

Nathan Wolfe: Virus Hunter

You can watch a fascinating TED Talk by Dr. Wolfe HERE on preventing the `next pandemic’.