Credit CDC Ebola Website

# 8911

Amid the hype and hoopla in the tabloids, on social media, and (regrettably) even the mainstream news over the risks of Ebola spreading widely or becoming a global pandemic, one obvious fact seems glaringly absent.

If Ebola were anywhere near as contagious as the fear mongers would have us believe - after more than five months of spread - we’d be talking about hundreds of thousands of deaths in West Africa . . . not hundreds.

Even assuming that the case counts we have badly understate the scope of the outbreak, and it is triple that which has been reported, the numbers still don’t suggest an easily transmissible disease. By comparison, five months after the relatively mild 2009 H1N1 virus appeared, millions had been infected around the world and tens of thousands had died.

Fortunately, to help offset this hysteria, there’s been some excellent reporting by the likes of Maggie Fox at NBC news, Helen Branswell of the Canadian Press, Declan Butler of Nature, and Dr. Richard Besser of ABC News. Bloggers like Dr. Tara C. Smith have produced excellent, reasoned, posts as well (see Are we *sure* Ebola isn’t airborne? & Ebola is already in the United States).

But I’m also seeing a backlash by some in public health communications - born, I would suspect, out of growing frustration of dealing with those who see doomsday or some kind of government conspiracy at every turn – to dismiss as unreasonable the public’s fears of the disease.

While perhaps not firmly rooted in science, or even logic, the public’s apprehension is certainly understandable.

For more than a decade, governments in the US and around the world have warned the public about an imminent `bio-terror’ threat, and about exotic emerging infectious diseases like `Bird Flu’ and SARS. Movies and novels like Contagion and The Stand have painted a stark vision of the next pandemic, while Ebola has been used as the viral villain in a number of thrillers ranging from Tom Clancy’s Executive Orders to The Hot Zone by Richard Preston.

Now, suddenly, the government finds itself trying to dial back some of these concerns, and frankly, that isn’t going to be easy.

While it is important to be very clear that the Ebola outbreak in West Africa poses a negligible risk to residents of the United States, I worry that the reassurance pendulum may be swinging too far in the simplistic, `don’t worry, be happy’ direction.

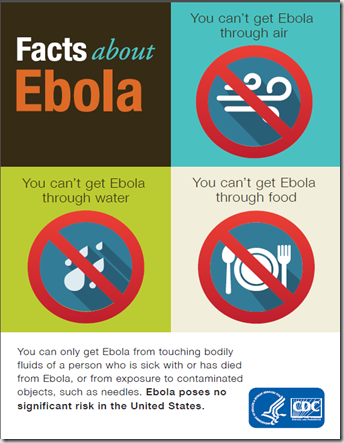

Exhibit A, posted yesterday, by the CDC follows:

I know, I know. Ebola isn’t considered an airborne virus, and you aren’t going to get it through your tap water, or food here in the United States. And it’s true, Ebola really isn’t likely to pose a significant threat here.

But I worry do that anyone who sees this infographic – and compares it to the Ebola Infection Control Guidance or to pictures of `moon-suited’ healthcare workers working with Ebola cases – is going to come away feeling they are being placated like an overly protective parent would an anxious child.

Sometimes the perception is as important as the message.

While miniscule – the risks of infection if you are in close proximity to an Ebola patient (which is highly unlikely, BTW) are probably a tad more complex and nuanced than this infographic suggests. One need only look at the CDC’s guidance Management of ill people on aircraft if Ebola virus is suspected to get a slightly different perspective:

Crew members on a flight with a passenger or other crew member who is ill with a fever, jaundice, or bleeding and who is traveling from or has recently been in a risk area should follow these precautions:

- Keep the sick person separated from others as much as possible.

- Provide the sick person with a surgical mask (if the sick person can tolerate wearing one) to reduce the number of droplets expelled into the air by talking, sneezing, or coughing.

- Give tissues to a sick person who cannot tolerate a mask. Provide a plastic bag for disposing of used tissues.

- Wear impermeable disposable gloves for direct contact with blood or other body fluids.

Anyone reading the above recommendations, and viewing the infographic, must surely wonder if they are about the same virus. While simple declarative sound bites are usually best when trying to convey any message to the public, sometimes they can be too simple, and too reassuring for their own good.

I get it. I really do. Finding the right message isn’t easy. And no, I don’t have a great solution.

The fact that the lunatic fringe have taken over much of the media and internet make it almost impossible for public health officials to engage in serious public discussions about risks without every word being blown out of proportion. Suggest even the possibility of an untoward event, and you’ve written the next tabloid headline and guaranteed the next 24 hour news cycle.

The sobering part of all of this is that the next global health threat – whether it be from H7N9, MERS-CoV, H5N1, or Virus X – could pose a far greater threat to our national security and public health than a virus like Ebola ever could.

Yet the same problems of risk communications – amid the sound and fury of the mainstream and social media – will persist, and likely only grow worse with time. Making it all it all the more important that the CDC retain the public’s trust during this disease threat, if they hope to carry it through the next one.