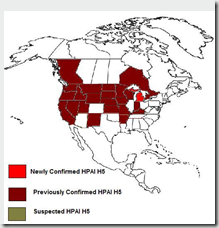

Winter-Spring 2015 Bird Flu Outbreaks

# 10,777

While avian flu has yet to affect any commercial flocks in the United States this fall, after the carnage last spring, no one is suggesting the the threat is passed. Elsewhere in the world (Korea, Vietnam, West Africa, France, etc.) we are seeing an uptick in avian flu reports, and so continued vigilance is required.

Although the first American reports came in mid-December last year, it wasn’t until after the New Year that we started to really see the virus take off. With a record-setting El Nino underway, this year’s weather patterns are decidedly different from last’s, and that may affect the timing and spread of the virus.

In the meantime the USDA/APHIS has published the following update.

USDA Continues to Prepare for Any Possible Findings of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza

Published: Dec 4, 2015

Washington, December 4, 2015 – The United States Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (USDA APHIS) continues to prepare for any potential findings of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI). An outbreak of HPAI during spring and summer 2015 was the largest animal health emergency in the country’s history. APHIS and its partners worked throughout the fall to put plans in place to address the disease should it reappear.

The United States has the strongest AI surveillance program in the world, and USDA is working with its partners to actively look for the disease in commercial poultry operations, live bird markets and in migratory wild bird populations. As part of the wild bird surveillance effort, APHIS and its wildlife agency partners will be sampling more than 40,000 wild birds between July 1, 2015 and July 1, 2016 – with more than 24,000 samples already tested. Samples are being collected from both hunter-harvested birds and from wild bird mortalities.

As part of these surveillance efforts, Eurasian H5 avian influenza was recently found in genetic material collected from a wild duck, but testing was unable to determine the exact strain of the viruses or whether they were high pathogenic or low pathogenic. This recent finding of Eurasian H5 was in a wild, hunter-harvested mallard duck in Morrow County, Oregon in November. No HPAI has been identified in any commercial or backyard poultry since June 17, 2015.

On November 18, USDA reported to the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) that all cases of HPAI in commercial poultry have been resolved and that the US is again free of HPAI.

Producers and the industry are working to enhance their biosecurity on farms to help provide an even better protection against the virus should a reappearance of HPAI occur. Anyone involved with poultry production from the small backyard to the large commercial producer should review their biosecurity activities to assure the health of their birds. To facilitate such a review, a biosecurity self-assessment and educational materials can be found at http://www.uspoultry.org/animal_husbandry/intro.cfm

In addition to practicing good biosecurity, all bird owners should prevent contact between their birds and wild birds and report sick birds or unusual bird deaths to State/Federal officials, either through their state veterinarian or through USDA’s toll-free number at 1-866-536-7593. Additional information on biosecurity for backyard flocks can be found at http://healthybirds.aphis.usda.gov.

Additional background

Avian influenza (AI) is caused by an influenza type A virus which can infect poultry (such as chickens, turkeys, pheasants, quail, domestic ducks, geese and guinea fowl) and is carried by free flying waterfowl such as ducks, geese and shorebirds. AI viruses are classified by a combination of two groups of proteins: hemagglutinin or “H” proteins, of which there are 16 (H1–H16), and neuraminidase or “N” proteins, of which there are 9 (N1–N9). Many different combinations of “H” and “N” proteins are possible. Each combination is considered a different subtype, and can be further broken down into different strains. AI viruses are further classified by their pathogenicity (low or high)— the ability of a particular virus strain to produce disease in domestic chickens.