#10,983

Although the primary concern right now with the Zika virus is its tentative link to microcephalic birth defects, a secondary concern has been the concurrent rise in the number of Guillain-Barre syndrome cases in French Polynesia and South and Central America following Zika's arrival.

Today, a brief overview of this rare neurological condition.

Not quite 40 years ago Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS) made global headlines following the roll-out of the 1976 emergency swine flu vaccine, which after 40 million doses were administered, was linked to roughly 500 cases of (mostly temporary) paralysis and 25 deaths.

I was a young paramedic at the time, and chronicled my little part in that bit of influenza history several years ago in Deja Flu, All Over Again.

In the nearly 4 decades since that fiasco, there has been little or no evidence of flu shots causing Guillain-Barre Syndrome - and since influenza infection has been linked to causing GBS - the flu shot is believed to have reduced the number of GBS cases over the years (see Lancet: The Influenza - Guillain Barré Syndrome Connection).

While the exact cause of GBS isn't well understood, we do know that most cases occur after a bacterial or viral infection. Camplyobacter Jejuni, in particularly, has been linked to GBS, but other bacterial and viral infections (including influenza and Dengue) have as well.

GBS isn't a single neurological illness, but rather a collection of syndromes all of which damage nerve cells, resulting in muscle weakness and sometimes paralysis. With modern medical treatment (including Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), plasma exchange, and ventilatory assistance if needed), most victims survive.

But between 5%-10% of GBS cases are fatal, and a large percentage of survivors carry forward some form of neurological sequelae (cite), including motor deficits, persistent fatigue, and sensory loss.

There are a number of GBS variants (whose symptoms often overlap) with their incidence varying around the world. A few of the major subtypes include:

- Acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (or AIDP) is the most common form of GBS reported in the United States.

- Acute motor axonal neuropathy (AMAN) is more prevalent in pediatric age groups, with many cases reported in rural China. Once again, C jejuni infection is often linked to onset.

- Acute motor-sensory axonal neuropathy (AMSAN) typically affects adults.

- Miller-Fisher syndrome is observed in about 5% of all cases of GBS, and presents as a triad of ataxia, areflexia, and ophthalmoplegia. Recovery generally occurs within 1-3 months.

- Acute panautonomic neuropathy is the rarest GBS variant, Cardiovascular involvement is common and recovery is often slow and incomplete.

Now that polio is no longer a factor, GBS (in all of its forms) is the primary cause of acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) in the the United States with an incidence of between 1.2 and 3.0 per 100,000 (3,000 to 9,000 cases annually).

In 2011 we looked at a rare cluster of GBS linked to C jejuni water contamination in The Sonora/Arizona GBS Cluster, but most cases are one-offs, and are not epidemiologically linked.

Almost two years ago, in Zika, Dengue & Unusual Rates Of Guillain Barre Syndrome In French Polynesia, we saw an outbreak of Zika in the South Pacific that – quite unusually – seemed to be linked to an increase in Guillain Barré Syndrome cases. In March 2014 the journal Eurosurveillance carried a Rapid Communications describing the first case and reporting a 20-fold increase in GBS during the outbreak.

Since then we've seen apparent spikes in GBS in Brazil, El Salvador, and other regions where Zika has recently emerged. While a causal link has not been established, the WHO cited the rise in GBS as one of the factors in declaring Zika a public health emergency a week ago, and on Friday CDC director Thomas Frieden indicated that the linkage between Zika and GBS grows stronger the more we learn.

Infection by other mosquito-borne viruses - such as Dengue, Chikunungya, EEE, and West Nile Virus - are known to occasionally cause serious neurological symptoms, including AFP (acute flaccid paralysis), making a Zika-GBS link at least plausible.

While the literature isn't exactly overflowing, some relevant links include:

Guillain-Barre syndrome following dengue fever and literature review.

Guillain-Barre syndrome occurring during dengue fever.

Guillain-Barré Syndrome after Chikungunya Infection

Neuromuscular Manifestations of West Nile Virus Infection

The good news in all of this is that neuroinvasive illness from arboviral infections (Dengue, CHKV, WNV, and Zika) are very rare, and many infections can be avoided by taking some simple mosquito precautions.

|

| The 5 D's of Mosquito Protection |

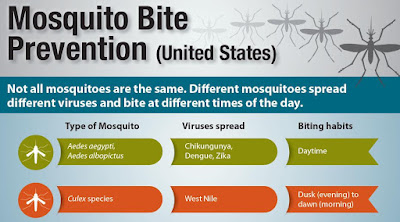

It should be noted that the Aedes mosquitoes, linked to Zika and Dengue transmission, are aggressive daytime biters - and so it is important to protect yourself throughout the day.

And lastly, a 2003 CDC EID study found that economics and lifestyle (window screens, A/C, etc.) may help to limit the spread of arboviruses in the United States (see Texas Lifestyle Limits Transmission of Dengue Virus) - at least compared to many tropical regions.

None of this is to suggest there won't be some places in the U.S. that could see limited outbreaks of Zika, only that the kind of pervasive spread we've seen in Central and South America seems unlikely in the United States at this time.