#13,226

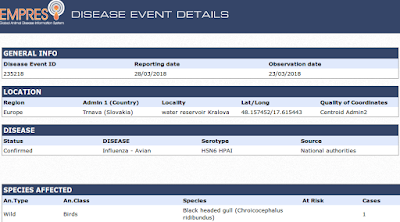

Although it has yet to appear in the OIE listings, overnight the Slovakian SVPS (State Veterinary and Food Administration) has posted an announcement, and the FAO has filed a brief report, on HPAI H5N6 discovered in dead wild birds recovered from the water reservoir in the Kráľová district.

First a screen shot of the FAO report, followed by the SVPS announcement. After which, I'll return with a bit more.

(Continue . . . )

Current information on the occurrence of avian influenza subtype H5 in Slovakia

On 28.03.2018 was the result of laboratory reference laboratory VU Elected confirmation of avian influenza subtype H5 in wild birds. Outbreaks confirmed the water reservoir Kráľová district. Galanta the headed Gull ( Chroicocephalus ridibundus ). It is a high - pathogenic type H5N6 confirmed in one of the 5 found dead seagulls.

Based on genetic analyzes of relatedness in terms of virus isolates originating from Japan and Taiwan, which circulated in the years 2016/2017. In 2017 spread to Europe circulation was recorded in Greece, followed by UK, NL, DE, SE, DK.

Regional Veterinary and Food Administration in Galante, in this context ordered the respective hunting associations steps of setting a monitoring area with a radius of 3 km from the place of finding and also increased surveillance of wild bird populations, in particular water fowl, and further monitoring for dead or sick birds, cooperation with ornithological organizations and reporting obligation to DVFA Galanta. He was further ordered a ban on hunting of wild birds as well as a ban on otherwise taking them from the wild unless it is authorized by the competent authority for specific purposes and that discharges of game birds from captivity into the wild.

In the place of judgment / confirmation of there are no poultry holdings (a place on the waterfront tank Králové). Within a radius of 3 km it falls part of one community (Kajal), where in addition to a listing of all breeds of poultry, pigeons and other birds kept in captivity prescribes measures to prevent the introduction of disease in herds, including preventing direct and indirect contact farmed birds with wild birds and informing the public about the measures ordered.

In connection with the above, it is necessary to be very careful with regard to the risk of spreading infection in the Slovak Republic. Defense against the outbreak in farms is prevention. As a precautionary measure (many are still part of the current extraordinary emergency measures) pointed out:

While it may be a limitation of the machine translation, the above report appears to link this HPAI H5N6 discovery to both the HPAI H5N6 virus that circulated in Japan and Taiwan in 2016/2017 and to the HPAI H5N6 that emerged in Greece, followed by UK, NL, DE, SE, DK in 2017.

Those are, in fact, two different lineages of H5N6.The 2016 H5N6 virus in Japan and Taiwan was related to the China's H5N6 virus - which has infected more than a dozen humans - while the 2017 European H5N6 is a reassortant of the 2016/2017 H5N8 virus which to date, is not known to have infected humans.

Based on reporting from other European countries this winter, this report is almost certainly related to the European reassorted lineage.While it hasn't sparked the kind of large scale avian epizootic we saw last year with H5N8 - both HPAI H5N8 and HPAI H5N6 have shown remarkable persistence, and an expanded host range - in wild birds.

And that is a fairly recent change.In 2015 we looked at a study (see PNAS: The Enigma Of Disappearing HPAI H5 In North American Migratory Waterfowl) which concluded that while migratory waterfowl can briefly carry HPAI H5, they were not a good long-term reservoir for highly pathogenic avian flu viruses.

HPAI viruses appeared to burn out fairly quickly in aquatic waterfowl populations - likely due to their immunity to LPAI viruses - and would therefore have to be reintroduced periodically.That changed in the fall of 2016 when H5N8 returned to Europe and brought with it a number of genetic and behavioral changes attributed to a reassortment event that likely took place sometime in the spring of 2016 (see EID Journal: Reassorted HPAI H5N8 Clade 2.3.4.4. - Germany 2016).

A newer study, published in 2016 (see Sci Repts.: Southward Autumn Migration Of Waterfowl Facilitates Transmission Of HPAI H5N1), suggests that waterfowl pick up new HPAI viruses in the spring (likely from poultry or terrestrial birds) on their way to their summer breeding, spots and then redistribute them on their southbound journey the following fall.With migratory birds headed now north to their summer roosting areas, the concern is that these newly persistent HPAI H5 viruses could hitch a ride and spend their summer vacation in the high latitudes - perhaps reassorting with other viruses - and producing new avian subtypes which could return next fall.