# 2959

Just available online today from the CDC’s Journal of Emerging Infectious Diseases – in an ahead of print article – we get an overview of three of the automated infectious disease surveillance systems being used on the Internet.

The study, entitled - Use of Unstructured Event-Based Reports for Global Infectious Disease Surveillance M. Keller et al. (429 KB, 15 pages) – gives deep background on the creation and functioning of Global Public Health Intelligence Network (GPHIN), Healthmap, and Episider.

DOI: 10.3201/eid1505.081114

Suggested citation for this article: Keller M, Blench M, Tolentino H, Freifeld CC, Mandl KD, Mawudeku A, et al. Use of unstructured event-based reports for global infectious disease surveillance. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009 May; [Epub ahead of print]

This study is a good read, particularly if you are interested in how semi-automated data mining for infectious disease outbreaks is accomplished, and the limitations of these types of systems.

As the authors state, there is a certain amount of `background noise’ and `clutter’ that comes from these automated systems.

Still, during the very early days of testing of GPHIN – between July 1998 and August 2001, WHO retrospectively verified 578 outbreaks, of which 56% were initially picked up and disseminated by GPHIN.

That’s not bad for an automated system.

GPHIN requires a paid subscription, but the other two event gathering websites are free to access.

Healthmap (see above) was begun in 2006, and is fully interactive. I first wrote about HealthMap in July of 2008 (see HealthMap On The Web)

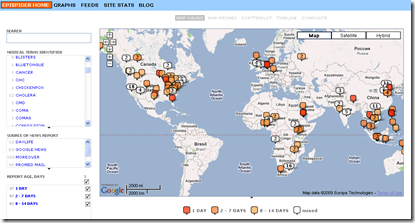

EpiSider (below) also uses a user interactive map, and provides some very interesting graphing capabilities as well.

As the CDC EID Journal study points out (reformatted for readability):

Discussion

Despite their similarities, the 3 described event-based public health surveillance systems are highly complementary; they monitor different data types, rely on varying levels of automation and human analysis, and distribute distinct information.GPHIN, being the longest in use, is probably the most mature in terms of information extraction.

In contrast, HealthMap and EpiSPIDER, being comparatively recent programs, focus on providing extra structure and automation to the information extracted.

And of course, these aren’t the only disease information gathering systems mining data from the Internet.

Our flu forum newshounds (see Newshounds: They Cover The Pandemic Front) perform similar duties, and of course ProMED Mail is a well established infectious disease Surveillance System.

Recently, Google.org unveiled their Flutrends website, and now Twitter is even getting into the act with a mashup called SickCity.

In 2003, the first inkling that a serious disease outbreak (SARS) had occurred in China came from `Internet Chatter’ that the sale of Vinegar had gone through the roof in China.

In China, boiling vinegar in the home is a traditional way to protect the inhabitants against respiratory diseases.

As Helen Branswell of the Canadian Press reminded us, in her article last May entitled SARS memories linger 5 years later, it was the monitoring of the Internet that produced the first clues that something very bad was happening in China:

Surging vinegar sales in China grabbed the attention of the folks who regularly scour the globe for what might be budding disease outbreaks, like those who work for the Canadian-led Global Public Health Intelligence Network.

"We were getting lots of rumours, like a lot of sales of vinegar," explains Dick Thompson, who was the spokesperson for the World Health Organization's communicable diseases section at the time.

There is a pretty good chance that our first inkling that a new SARS, or some other infectious disease outbreak, will come first from a news story, or forum chatter, off the Internet.

The hope is, if we can pinpoint an outbreak early enough, public health officials might be able to contain an epidemic before it gets out of control.

And while things may not turn out that way, it is certainly something to shoot for.