# 3272

Note: Today’s blog is about pandemics in general, and may not pertain to the H1N1 we are currently watching circle the globe.

I imagine that one of the thinnest books one could ever aspire to write would be called: Things We Know For Sure About The Next Pandemic.

And there is good reason for this uncertainty. Influenza viruses, and pandemics, are unpredictable.

As virologists like to say:

“If you’ve seen one pandemic . . . you’ve seen one pandemic.”

We often look back at history to try to figure out what will happen in the future. Sometimes that works, sometimes it doesn’t.

Even relatively simple sounding questions, like How long will a pandemic last? are almost impossible to answer.

The standard answer is pretty vague.

Influenza pandemics often come in two or more waves several months apart, and each wave can last 6 to 8 weeks in a particular location. It is difficult to predict how far apart the pandemic waves will be or how long a pandemic will last.

The problem is, in the 100 years or so that we have reasonably good data, we’ve seen considerable variability between the three pandemics (and assorted pseudo-pandemics) that have swept the globe.

If history is any guide, the worst of any influenza pandemic should be over in a year or two.

But that doesn’t mean that the pandemic virus, or its impact, will have completely gone away after that time period.

Most historians will tell you that the granddaddy of all modern pandemics – the 1918 Spanish Flu – circled the world for about 18 months, coming over 3 waves.

The Wikipedia lists the 1918 pandemic as having lasted from March of 1918 to June of 1920.

The following graphs come from:

REVIEW AND STUDY OF ILLNESS AND MEDICAL CARE WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO LONG-TIME TRENDS

Public Health Monograph No. 48, 1957 (Public Health Service Publication No. 544)

The 1918 pandemic virus continued to produce relatively serious spikes of illness across the United States for most of the decade of the 1920s.

Presumably these waves of excess mortality were experienced in other places around the world as well.

(click to enlarge)

(Note: the scale of these two graphs are different)

The two main spikes of 1918 and 1919 are readily apparent, but as you can see, there were significant increases in P&I mortality rates in 1922, 1923, 1926, and 1929.

Nothing to compare with the 1918-1919 outbreaks of course, but significant if you were caught up in one.

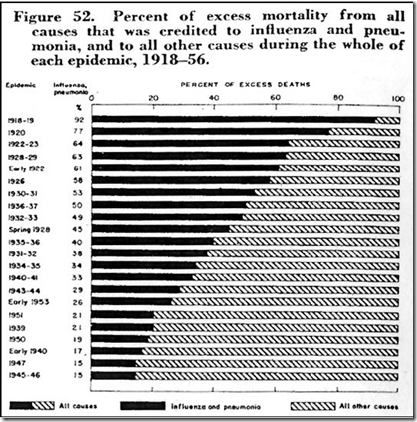

Again, the above graphic shows that the top 6 time spans between 1918 and 1956 for percentage of excess P&I mortality were all in the decade following the 1918 pandemic.

In comparison, the 1930’s and 1940’s were especially quiescent when it came to Pneumonia and Influenza mortality.

The `Asian Flu’ of 1957 is generally thought of as having 2 waves, spanning from about October of 1957 to April of 1958.

But a look at the pandemic waves associated with the Asian flu shows that significant spikes in P&I (Pneumonia and Influenza) mortality continued until 1963.

Once again, the impact of the 1957 pandemic appears to have stretched far beyond the 1957-1958 timeframe.

For reasons that are far from clear, the H2N2 virus `skipped’ several flu seasons, only to reappear with vigor in 1963.

Which makes answering the question about `how long will a pandemic last’ impossible.

Pandemics occur when a well adapted, yet antigenically ‘new’ virus begins to circulate among humans. As people are exposed to the virus, or are vaccinated, they develop antibodies (immunity) against it.

When a sufficient percentage of the population develops (herd) immunity (or a virus mutates to something less `fit’), a pandemic winds down. Case levels drop below the epidemic threshold, and the pandemic is declared to be over.

But viruses are unstable, and mutate constantly, thus evading acquired immunity. Even years after a pandemic is over, the responsible virus can flare up in some localities, and cause significant morbidity and mortality.

Complicating matters is the fact that there is no clear signal that can tell us when the last pandemic wave has passed.

We can only know that by looking back, months or even years later, and seeing that no new wave appeared.

Obviously, if I wanted to write a really thick book, I’d have to call it: Things We Don’t Know About The Next Pandemic.