# 3137

In the Southern Hemisphere, it is already Fall. Temperatures are declining, and Winter is only 6 weeks away.

(maps from the Wikipedia)

With Winter comes flu season, which ought to be ramping up over the next few weeks in places like South Africa, New Zealand, and Australia.

The tropics, which is a subset of both the Northern and Southern Hemisphere, doesn’t have a `flu season’ per se. Influenza circulates, usually at a low level, year round.

With a novel influenza virus suddenly appearing at the end of our flu season in the Northern Hemisphere, all eyes will be on the Southern Hemisphere over the next few months to see how `fit’ the virus is, and to get some idea of what our next flu season may bring.

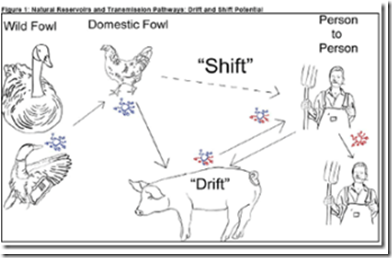

Fig. Birds, humans, and Pigs are all susceptible to Influenza

The A/H1N1 has the potential to mutate (drift) or reassort with other flu viruses (shift), which could result in a more virulent strain. The more people (and other hosts) who acquire the virus, the more chances the virus has to evolve.

Of course the virus could lose virulence, or even its ability to spread, as well. We’ll just have to wait and see.

While the public’s attention is on this new, emerging virus, scientists have long known that abrupt changes can occur even in well established seasonal flu viruses.

The infamous `Liverpool Flu’ of 1951 has faded from most people’s memory, but for about 6 weeks a super-virulent strain of flu swept out of north western England, killing at a rate faster than the pandemic of 1918.

I chronicled the details of this outbreak last October in Sometimes . . . Out Of The Blue, but briefly: for about 6 weeks the UK (and to a lesser extent Canada), saw a horrific rise in flu fatalities in 1951.

This `rogue flu’, for reasons we don’t fully fathom, disappeared as suddenly as it appeared.

While we are learning more every day, there is still a great deal that scientists do not understand about how influenza viruses spread and evolve.

As virologists like to remind us, `Shift Happens’.