# 3446

It has been pretty obvious for some time that this novel swine flu virus isn’t in the same league as bird flu (H5N1), or the 1918 Spanish Flu (another novel H1N1).

The question that remains unanswered is: Just how deadly is it?

And unfortunately there isn’t one answer to that question. Nor is there likely to be.

A pandemic isn’t a static event, and the virus – carried simultaneously by millions of hosts – doesn’t change direction and speed in concert like a school of fish.

Instead, what you have are millions of hosts incubating trillions of virus particles – with mutational changes occurring all of the time. Most of these changes do not benefit the virus and lead nowhere, but out of trillions of rolls of the dice, some small number do.

It is survival – and propagation – of the biologically fittest.

Evolution in action.

With viruses that are better adapted to humans out-replicating, out-shedding, and out-transmitting lesser versions of the pandemic strain.

And that means that the virus we have in circulation today may not be the same virus we have running around in the fall, next winter, or next year sometime. We could potentially see changes in virulence or antiviral sensitivity over time.

Which means there are likely to be pockets of stronger, and weaker, strains of this virus around the world as this pandemic evolves.

Of course, a mutation that favors the virus needn’t make the virus more virulent. It could be a mutation that simply makes it replicate more efficiently, or transmit more easily from human to humans.

In 1947-48, a mild influenza virus – one that produced very low mortality rates – spread rapidly around the world. It caused a lot of sickness, but very few deaths. It is little remembered today, simply because it didn’t kill very many people.

But in 1950-51, a deadly strain of influenza emerged in Liverpool, England, flared briefly – spreading to Wales, and even to eastern Canada – killing at a rate higher than the 1918 Spanish Flu.

For reasons unknown, it stopped after 6 weeks (see Sometimes . . . Out Of The Blue). These are just two examples that illustrate why scientists call influenza `unpredictable’.

Simply put, Influenza viruses change. That’s what they do.

When we speak of virulence, we also need to consider exactly who is getting sick, and dying.

We’ve heard, of course, that those with pre-existing conditions are at particular risk from this virus. Asthma, diabetes, pregnancy, and respiratory diseases seem to lead the way here.

And normally, advanced age (over 65) is considered a risk factor as well.

But in the case of pandemic influenza, the percentage of those under the age of 65 experiencing severe illness tends to go up dramatically.

Pandemic versus Epidemic Influenza Mortality: A Pattern of Changing Age Distribution

Lone Simonsen,* Matthew J. Clarke, Lawrence B. Schonberger, Nancy H. Arden, Nancy J. Cox, Keiji Fukuda

(excerpts)

During the 1957–1958 influenza A (H2N2) pandemic, persons <65 years old accounted for 36% of all excess influenza-related deaths.

Over the next decade this proportion decreased to 4%, corresponding to a 28-fold reduction in the absolute risk

During the 1968–1969 influenza A (H3N2) pandemic, persons <65 years old accounted for 48% of all influenza-related excess deaths (table 3).

This proportion decreased to 10% after 1 decade (1980–1981 season) and has averaged approximately 5% during later influenza A (H3N2) seasons.

This pattern was even more pronounced in the 1918 Spanish flu. And in each case, heightened levels of excess mortality were recorded for years after the pandemic `officially’ ended.

When you get 10 or 20 years out from the last pandemic, those under 65 years of age generally make up about 5%-10% (sometimes less) of the annual seasonal flu deaths.

Pandemics, even mild ones, upset this ratio.

And while all influenza deaths are regrettable, the deaths of children and young adults are particularly tragic and difficult to deal with.

It isn’t uncommon that an influenza virus will re-emerge after a number of years of being out of circulation.

We saw that in 1977, when the H1N1 virus returned after a 20 year absence. Those under the age of 20 had no immunity, and so they were hit the hardest by its return.

We may be seeing something similar here, with people born sometime before 1957 perhaps having some degree of immunity to this swine flu virus.

Whether that holds up over time remains to be seen, but for now, those over 65 are seeing relatively little effect from this virus.

And that, of course, skews the numbers. We could see fewer deaths overall from this virus, yet still suffer a tremendous impact simply because of the ages of those who are killed by the pandemic.

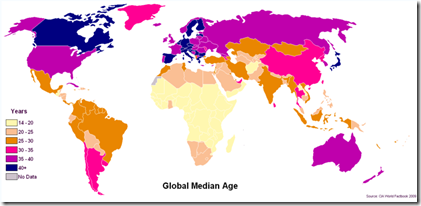

Countries like Canada, the United States, Australia, and much of Europe are `older’ in population than countries in Africa, Asia, and South America.

The younger the median age of a country’s population, the greater impact that any pandemic is likely to have.

And the countries the youngest populations are, typically, the countries that are least able to deal with a large-scale health crisis like a pandemic.

And that brings up the third major variable.

The ability of different countries (and regions) to provide medical care to those stricken with the virus. Vaccines, antivirals, and even antibiotics – in much of the world – are a distant dream.

Individuals who might very well survive in an industrialized country, with access to modern medical interventions, might not fare as well in other parts of the world.

And lastly, the sheer number of people who are likely to be infected during the opening years (yes, years) of a pandemic are likely to be several times greater than we normally see from seasonal influenza.

More people sick means more people are at risk of complications, and death. Even if the percentage of people dying isn’t any greater than with seasonal flu.

And so, when you take the variability of the virus, the age shift of mortality, the disparities in medical care, and the number of people likely to be infected . . .

Well, we could see very different pandemics in different parts of the world, and perhaps fluctuations in severity over time.

Of course, right now a lower CFR pandemic beats a higher CFR pandemic any day. And it is hard not to be a little heartened by the numbers we’ve seen.

But we shouldn’t be lulled into complacency by this apparent good news. Even low CFR pandemics are capable of inflicting tremendous damage.

And where you live, your age, health, and no small amount of luck may determine how big an impact this pandemic will have on you and your family.

We all need to be thinking about how we can best prepare our families, our businesses, our neighborhoods, and our greater community to deal with this approaching crisis.

Something to think about (and act on) as the clock ticks, and this virus spreads around the world.