# 3685

Viral infections during the winter months are as ubiquitous as they are difficult to identify. Doctors see them every day, but most of the time, their etiology remains uncertain.

“You’ve picked up a virus.”, may very well be the most common utterance of a GP during the flu season.

Testing can be expensive, inaccurate, and often an exercise in futility. Most viral infections run their course in 3 to 5 days, and are over and done with before any laboratory tests can come back.

Office tests, such as the RIDT (Rapid Influenza Diagnostic Test) are notorious for their inaccuracies. The CDC recently released guidance for physicians explaining why a NEGATIVE test should not be used to exclude influenza as a diagnosis.

Essentially, a positive test will generally be correct. A negative test may miss 50% of influenza cases, and so doctors are advised to use clinical evaluation to make the diagnosis.

The problem, of course, is that the symptoms for influenza are pretty much the same as the symptoms for a great many other viral infections; fever, malaise, body aches, cough.

What looks like `flu’ could just as easily be parainfluenza, a rhinovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, metapneumovirus, or adenovirus – to name a few.

Complicating matters this year is the novel H1N1 virus, which has swept across the globe over the summer. While it is a mild-to-moderate illness in the vast majority of patients, in some small percentage of people it produces severe – even life threatening symptoms.

With no reliable rapid detection test, physicians (and the public) are called upon to make a diagnosis based on clinical symptoms.

That may prove difficult, as we learn from this Lancet article, since the novel H1N1 virus can produce atypical symptoms in a surprisingly high percentage of patients.

A hat tip to Niko on Flutrackers for posting this study.

Clinical characteristics of paediatric H1N1 admissions in Birmingham, UK

S Hackett a, L Hill a, J Patel a, N Ratnaraja b, A Ifeyinwa b, M Farooqi b, U Nusgen c, P Debenham c, D Gandhi c, N Makwana b, E Smit a d, S Welch a

Our experience of the first wave of paediatric H1N1 swine-origin influenza admissions in Birmingham, UK, shows that presentations can be atypical, severity is often associated with underlying disease, and rates of secondary bacterial infection are low.

We reviewed the 78 available case notes of 89 children positive for H1N1 influenza by PCR admitted to hospitals across our three Trusts between June 5 and July 4, 2009.

A confusing array of symptoms reported in Pediatric Patients

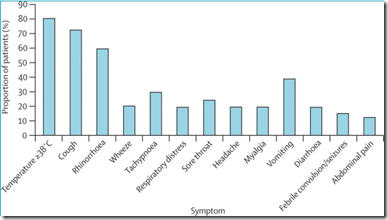

In the UK the HPA (Health Protection Agency) produced a case definition of H1N1 for doctors to use to make a clinical diagnosis of the illness. That called for a temperature ≥38°C or a history of fever and two other symptoms of cough, sore throat, rhinorrhoea, limb or joint pain, headache, vomiting or diarrhoea, or a severe or life-threatening illness

According to the researchers, To have followed the HPA algorithm would have meant that 40% of children with H1N1 influenza would not have been diagnosed.

It should be noted that this study involved kids sick enough to be admitted to the hospital, and yet 20% of them had no fever, and about 25% no cough.

A dilemma, obviously, for physicians. But most are pretty adept at telling when a child is really sick.

We don’t have good data on the spectrum of symptoms being experienced by those with milder illness, although it is likely to be similarly nebulous and diffuse.

Which may prove a big challenge for individuals and families who must decide, based on symptoms, whether to stay home from work or school to avoid spreading the virus.

Infected individuals can range from being completely asymptomatic, to mild to moderately symptoms, to severely ill.

And not everyone will present with `classic’ flu symptoms.

Which is the main reason why health officials have accepted that there is no reasonable way to contain, or halt, the spread of influenza in our communities.

It is the master of disguise, can operate in `stealth mode’, and is impossible to reliably identify 100% of the time.