# 4228

My thanks to Helen Branswell for alerting me (via her Twitter feed) to this article in The Economist about research conducted by two scientists at the San Diego Zoo’s Institute for Conservation Research on which animal species are likely to contract different types of influenza.

Influenza and wildlife

Mix and match

Jan 7th 2010

From The Economist print editionWhich animal species are most likely to get flu?

Science Photo Library

What, me?

THE scientific value of zoos is sometimes called into question, but Mark Schrenzel and Bruce Rideout, two experts on wildlife diseases who work at San Diego Zoo’s Institute for Conservation Research, have just shown the value of having a wide range of animals to hand for study. They have been looking at which species might act as reservoirs for influenza viruses and—worse, from the human point of view—which might act as “mixing vessels” in which new strains of virus are generated.

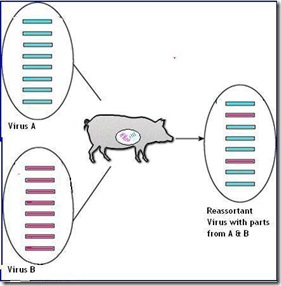

New strains of influenza come about from reassortment, or the mixing and matching of genetic material between two compatible flu strains in a shared host.

While any host (human, swine, avian) could produce a reassorted virus, hosts (like pigs) that are susceptible to a wider range of viruses are thought to be more likely to serve as an efficient mixing vessel.

Human adapted influenza have an RBD - Receptor Binding Domain (the area of its genetic sequence that allows it to attach to, and infect, host cells) that `fit’ the receptor cells commonly found in the human upper respiratory tract; the alpha 2,6 receptor cell.

Avian adapted flu viruses bind preferentially to the alpha 2,3 receptor cells found in the gastrointestinal tract of birds.

While there are some alpha 2,3 cells deep in the lungs of humans, for an influenza to be successful in humans, it needs to bind to the a 2,6 receptor cell.

(Very Simplified Illustration of RBDs)

Some mammalian hosts (like pigs) have both types of receptor cells, and therefore, increase the range of influenza viruses to which they are susceptible. And that, in turn, increases the odds that they could host two different viruses at the same time, and help facilitate a reassortment of two flu viruses into a new hybrid.

Drs. Schrenzel and Rideout at the San Diego Zoo have examined 60 different species of small mammals, and have determined that several carry the type of receptor cells (a2,3) favored by the H5N1 avian flu virus; including opossums, the Arctic Fox, and the Chinese wolf.

Additionally, we’ve seen H5N1 infections among dogs, cats, civets, raccoons, martens, and – of course – humans. And researchers have successfully infected cattle with the H5N1 virus, along with ferrets and mice for testing.

Over the years, scientists have openly wondered about possible mammalian reservoirs of the virus, which could help explain how the virus can be reintroduced to an area after massive poultry cullings have taken place.

The list of potential hosts is likely to continue to grow.

Schrenzel and Rideout have also identified a handful of small carnivores that carry both the a2,3 and a2,6 receptor cells, making them potential mixing vessels. These include the Persian leopard and the North American striped skunk.

For more on mammalian and avian hosts for influenza, you wish to revisit these blogs.

Japan: Bird Flu Antibodies Found In Raccoons

Reservoir Ducks

Reservoir Dogs (Cats, Foxes, and Raccoons)

And for more on RBDs, the following essays might be of interest.

Study: H1N1 Receptor Binding

RBD: Looking For The Sweet Spot

Receptor Binding Domains: Take Two

While we are learning more about influenza viruses, and the hosts they inhabit, we obviously have a long way to go. The novel H1N1 and H5N1 viruses have rewritten the science text books over the past five years, and more rewrites are likely in store.