# 6475

Although the attribution is suspect, there is an old adage in literary circles – credited most often to Russian playwright Anton Chekhov – that if you show a gun hanging on the wall in the first act, it absolutely must go off by the third.

It is such a well used device, that I suspect it leads many people to believe we are on the brink of a pandemic every time a novel influenza virus is reported in humans.

Fortunately, emerging infectious diseases are not compelled to follow the dictums of modern literary convention. New flu viruses are constantly cropping up in humans, but only rarely do they portend a pandemic.

With headlines last month on a novel H3N8 `Seal flu’ with supposed pandemic potential, and several small clusters of H3N2v swine flu infections in the Midwest over the past few weeks, today seemed like a good day take a historical look at a few viral contenders that tried, and failed, to spark a pandemic.

Novel flu viruses are most likely to be zoonotic; jumping from another animal species to man, either directly, or through an intermediary host, or via reassortment.

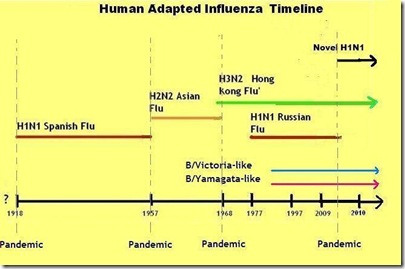

Over the past 100 years, we’ve seen four of these viral jumps spark a pandemic. The H1N1 pandemic of 1918, the H2N2 pandemic of 1957, H3N2 in 1968, and novel H1N1 in 2009.

But interspersed among these global pandemics have been numerous novel viruses that have infected humans and yet ultimately failed to produce a pandemic.

The most obvious example is the H5N1 virus, which first appeared 15 years ago in Hong Kong - and after a 5 year hiatus - returned in 2003.

Since that time has infected more than 600 people.

Yet despite morphing into more than 20 distinct clades, and spreading from Asia to Europe and the Middle East, this virus remains poorly adapted to human physiology and has (thus far) proved incapable of sparking a pandemic.

The caveat being, that this could change.

H5N1, like all flu viruses, is constantly evolving. As long as it is out there, it poses a potential pandemic threat.

Similarly, we’ve seen scattered human infections by the H9N2 avian virus, and sporadic attempts by various strains of the H7 avian virus to jump to man.

- In 2003 an outbreak of H7N7 at a poultry farm in the Netherlands went on to infect at least 89 people. Most of the victims were only mildly affected, but one person died.

- In 2004 two people in British Columbia tested positive for H7N3 (see Health Canada Report) during an outbreak that resulted in the culling of 19 million birds.

- In 2006 and 2007 there were a small number of human infections in Great Britain caused by H7N3 (n=1) and H7N2 (n=4), again producing mild symptoms.

But beyond these avian strains, we’ve seen human adapted flu viruses that have threatened – but ultimately failed – to spark a pandemic.

The first example comes from shortly after the end of WWII with what would become known as the `pseudo-pandemic’ or vaccine failure of 1947.

Fearing that crowded ships and barracks could give rise to a reprise of the 1918 pandemic, the United States Military commissioned Dr. Thomas Francis of the University of Michigan and his protégé Jonas Salk to come up with a viable influenza vaccine in 1943.

Within a year a vaccine based on the 1934 and 1943 flu strains was in wide use in the military, and for several years the Francis/Salk vaccine worked well.

But in 1947, a new variant of the H1N1 virus appeared on military bases in Japan,and quickly spread from there infecting hundreds of millions around the globe (see 2002 PNAS article).

While it produced a generally mild illness, and few excess deaths, this new strain apparently had drifted enough antigenically to evade both the vaccine and community immunity acquired from earlier strains.

Had it been more virulent, the 1947 flu virus might well have been considered a pandemic. Today it is barely remembered, except by virologists.

Four years later, a far more ominous flu strain made a brief appearance during the 1950-51 flu season.

For about six weeks, a highly virulent influenza erupted in Liverpool, England and then spread across the UK and to Eastern Canada.

For a time, it was as deadly as the 1918 pandemic.

This startling graphic comes from the March 16th, 1951 Proceedings of The Royal Society of Medicine – page 19 – and shows in detail the tremendous spike in influenza deaths in early 1951 over the (admittedly, unusually mild) 1948 flu season.

The CDC's EID Journal has a stellar account of this 1951 event, and is very much worth reading.

Viboud C, Tam T, Fleming D, Miller MA, Simonsen L. 1951 influenza epidemic, England and Wales, Canada, and the United States. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2006 Apr [date cited].

Despite its virulence, and obvious ability to spread efficiently from human-to-human, this virus died out as suddenly and mysteriously as it appeared.

It remains a medical mystery.

Fast forward to February 1976, and a young recruit at Ft. Dix, New Jersey fell ill and died from a virus that was later isolated and dubbed A/New Jersey/76 (Hsw1N1).

This swine-flu virus went on to infect more than 200 soldiers on the base, and caused severe respiratory disease in 13 of them. How and why it appeared in New Jersey remains unknown.

While the death rate was very low, this virus appeared to easily transmissible among humans. This led to the swine flu pandemic scare of 1976, which I chronicled several years ago in Deja Flu, All Over Again.

The feared swine flu pandemic never materialized, and for reasons we cannot explain, the virus simply disappeared.

In the `close but no cigar’ category, a year later we did see an epidemic - at least among children - with the return of the H1N1 virus after a 20 year absence. It was dubbed the `Russian Flu’, as it was believed to have escaped from a Russian research laboratory.

Given the limits of testing and surveillance, there have most certainly been other failed viruses – of which we are unaware – that simply `flu beneath our radar’.

In recent years we’ve also seen a number of non-flu viruses, such as the 2003 SARS outbreak, Clusters Of HEV68 Respiratory Infections, and various adenovirus outbreaks, that have produced illness and concerns, but no pandemic.

None of this tells us what will become of the H3N2v swine flu virus, or any of the other novel strains that are currently out there. Another pandemic will occur. We just don’t know when, or from what source.

But it does provide some perspective.

While all pandemics are caused by novel viruses, not all novel viruses produce pandemics.

Emerging viruses deserve our attention and respect, and H3N2v is certainly no exception. In time, this variant virus may prove to be a significant public health threat.

But as we watch these myriad novel viruses crop up around the globe, it should provide some solace to remember: history shows us that in the world of emerging infectious diseases . . .

. . . by the time act III comes along – we often find that Chekhov’s gun is loaded with blanks.