6-fold spike in encephalopathy during 2009 Pandemic Credit PLoS One

# 6908

While not viewed as having been a particularly severe pandemic, the 2009 H1N1 virus nonetheless caused serious, and sometimes fatal illness in a small percentage of patients.

And it did so in some pretty remarkable ways.

Seasonal influenza is primarily seen as a `harvester’ of the aged and infirmed, robbing its victims of the last few months or years of life, and only rarely does it seriously impact young adults and children.

Yet, in Study: Years Of Life Lost Due To 2009 Pandemic, we saw the mean age of death from the 2009 H1N1 virus to be half that of seasonal flu, or 37.4 years.

Severe lung injury, not normally seen with seasonal influenza, was also reported in a very small number of patients as well. We saw scattered reports during the summer and fall of 2009 (see Pathology Of Fatal H1N1 Lung Infections), but it wasn’t until December that the NIH: Post Mortem Studies Of H1N1 showed:

New York Autopsies Show 2009 H1N1 Influenza Virus Damages Entire Airway

In fatal cases of 2009 H1N1 influenza, the virus can damage cells throughout the respiratory airway, much like the viruses that caused the 1918 and 1957 influenza pandemics, report researchers from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the New York City Office of Chief Medical Examiner.

It was also widely reported (see Pregnancy & Flu: A Bad Combination) during the 2009 pandemic that pregnant women were up to 6 times more likely to be hospitalized with influenza than were non-pregnant women.

While many of these complications made headlines, somewhat less well publicized was the neurological impact this virus had on young children.

Barely 90 days after the novel H1N1 virus emerged, the CDC’s MMWR reported on 4 pediatric patients with the novel H1N1 virus who presented with neurological symptoms including unexplained seizures and altered mental status:

Neurologic Complications Associated with Novel Influenza A (H1N1) Virus Infection in Children --- Dallas, Texas, May 2009

Additional reports came in, particularly from Japan, indicating an unusual number cases of Influenza-related encephalopathy (IAE) among children (see Japan: Influenza Related Encephalopathy).

Encephalopathy isn’t a distinct disease, but rather refers to a syndrome of diffuse brain dysfunctions, which may be associated with a variety of causes (including viral, bacterial, trauma, prions, and toxic chemicals).

The overriding hallmark of encephalopathy is an altered mental state, although depending and severity of encephalopathy, common neurological symptoms such as progressive memory loss and changes in cognitive ability, personality changes, inability to concentrate, lethargy, seizures and loss of consciousness may be seen.

Over the past 15 years Influenza has been increasingly recognized as a rare cause of encephalopathy. For reasons not really known, is reported most often among children and adolescents in Japan and Taiwan.

In January of 2010, the CDC’s EID Journal carried a report called Neurologic Manifestations of Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Virus Infection and in September, the Annals of Neurology carried a study called Heightened Neurologic Complications in Children with Pandemic H1N1 Influenza that found:

The study looked at 303 children hospitalized with the pandemic H1N1 virus, of which 18 developed neurological symptoms.

They compared these cases to records of 234 children admitted to the hospital in previous years due to seasonal influenza.

The most common neurological complications exhibited with novel H1N1 were seizures (12 patients or 67%), with seven exhibiting status epilepticus, a potentially life-threatening condition involving continuous or recurrent seizures that can last for a half hour or longer.

The mean age of children admitted with neurological symptoms from H1N1 was more than twice the age (6.5 years) than usually seen with seasonal flu (2.4 years).

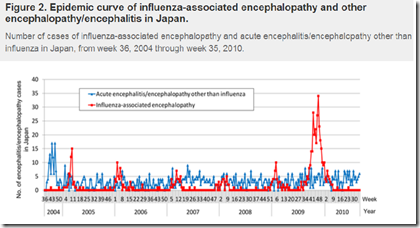

All of which serves as prelude to a research article that recently appeared in PloS One, that examined the rate of influenza-related encephalopathy in Japan across 6 flu seasons, including the 2009 pandemic.

National Surveillance of Influenza-Associated Encephalopathy in Japan over Six Years, before and during the 2009–2010 Influenza Pandemic

Yoshiaki Gu mail, Tomoe Shimada, Yoshinori Yasui, Yuki Tada, Mitsuo Kaku, Nobuhiko Okabe

Abstract (reparagraphed)

Influenza-associated encephalopathy (IAE) is a serious complication of influenza and is reported most frequently in Japan. This paper presents an assessment of the epidemiological characteristics of influenza A (H1N1) 2009-associated encephalopathy in comparison to seasonal IAE, based on Japanese national surveillance data of influenza-like illness (ILI) and IAE during flu seasons from 2004–2005 through 2009–2010.

In each season before the pandemic, 34–55 IAE cases (mean 47.8; 95% confidence interval: 36.1–59.4) were reported, and these cases increased drastically to 331 during the 2009 pandemic (6.9-fold the previous seasons).

Of the 331 IAE cases, 322 cases were reported as influenza A (H1N1) 2009-associated encephalopathy. The peaks of IAE were consistent with the peaks of the influenza epidemics and pandemics.

A total of 570 cases of IAE (seasonal A, 170; seasonal B, 50; influenza A (H1N1) 2009, 322; unknown, 28) were reported over six seasons. The case fatality rate (CFR) ranged from 4.8 to 18.2% before the pandemic seasons and 3.6% in the 2009 pandemic season. The CFR of pandemic-IAE was 3.7%, which is lower than that of influenza A−/B-associated encephalopathy (12.9%, p<0.001; 14.0%, p = 0.002; respectively).

The median age of IAE was 7 years during the pandemic, which is higher than that of influenza A−/B-associated encephalopathy (4, p<0.001; 4.5, p = 0.006; respectively).

However, the number of pandemic-IAE cases per estimated ILI outpatients peaked in the 0–4-year age group and data both before and during the pandemic season showed a U-shape pattern. This suggests that the high incidence of influenza infection in the 0–4 year age group may lead to a high incidence of IAE in the same age group in a future influenza season.

Further studies should include epidemiologic case definitions and clinical details of IAE to gain a more accurate understanding of the epidemiologic status of IAE.

This is a detailed, and interesting, analysis that finds that in addition to a 6 fold increase in cases during the pandemic, that (like the Annals of Neurology Study mentioned above) the median age of reported encephalopathy was twice that normally seen during other flu seasons.

The CFR (Case Fatality Ratio) of encephalopathy cases during the pandemic dropped, however, which the authors ascribe to `improved quality of diagnosis and treatment’.

Some of the 6-fold increase in IAE cases during the 2009 pandemic can probably be linked to increased public awareness and medical surveillance. Cases of mild IAE might have been transient, and not picked up by medical authorities during other flu seasons.

But when added to the other reports we’ve seen, the 2009 H1N1 virus does appear to have had some unusual properties. The authors conclude by writing:

In summary, national surveillance of AE in Japan revealed a steep increase in IAE cases during the 2009–2010 pandemic season. This was likely due to the large number of children infected with influenza during the pandemic, but social attention and information bias might have affected epidemiology data. Results of the present study revealed a relatively low CFR despite a large number of reported IAE cases during the pandemic. One of the characteristic findings was the age distribution of the reported IAE cases. Further studies should include strict epidemiologic case definitions, clinical details including medication history, and epidemiological information of IAE for a more accurate understanding of the epidemiologic status of IAE.

Nearly 4 years since the emergence of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, A/H1N109pdm is probably the most studied flu virus in history. While it did not end up being a particularly deadly pandemic virus, it has consistently yielded surprises.

- This was the first seasonal flu shown to infect both dogs and cats (see EID Journal: Pandemic H1N1 Infection In Cats) and showed up in such diverse animal hosts as turkeys and ferrets.

- Novel H1N1 also appears to differ from seasonal flu in how it is transmitted, at least according to researchers in Hong Kong who discovered that the novel H1N1 virus – unlike seasonal flu – easily infects and replicates in the conjunctival tissues of the eye (see I Only Have Eyes For Flu).

- And rather than completely supplanting the existing seasonal influenza A strains as we saw in the 1918, 1957 and 1968 pandemics, the 2009 pandemic virus now co-circulates with H3N2 (it did replace seasonal H1N1).

While some of these studies may seem a bit esoteric and limited in scope or impact, the knowledge we gain from them can hopefully prove an advantage to us the next time the world faces an emerging viral threat.