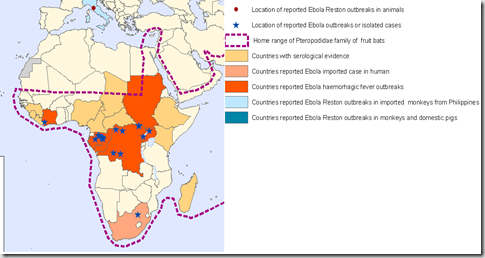

Range of Reported Ebola Outbreaks 1976-2014 – Credit WHO

# 8870

The story – confirmed this morning in the latest WHO update (see WHO Ebola Update – July 25th) – that a `probable’ Ebola patient (who died in isolation yesterday) traveled by airplane from Liberia to Lagos, Nigeria last Sunday `while symptomatic’ has captured headlines overnight.

Although the WHO statement did not elaborate on his symptoms, according to multiple media accounts (see here, and here) the patient became ill on the flight and vomited, and was quarantined upon landing.

Although I’ve not seen any description of the type of aircraft or number of passengers, according to a BBC report today (see Nigeria 'placed on red alert' over Ebola death), Health Minister Onyebuchi Chukwu is quoted as saying `. . . the other passengers on board the flight had been traced and were being monitored’ .

You may recall that a little over a month ago, we saw Spain Testing Traveler For Possible Ebola Infection, but in that case the patient tested negative.

At the time, we looked at the ECDC’s Rapid Risk Assessment on Ebola (June 9th), where experts worked out several scenarios where the Ebola virus might travel to the European Union, and their recommended response to Scenario 3: Passenger with symptoms compatible with EVD on board an airplane.

Similarly the CDC has also published their own guidance on how to deal with a probable or suspected Ebola case on an airplane.

Interim Guidance about Ebola Virus Infection for Airline Flight Crews, Cleaning and Cargo Personnel

Overview of Ebola Disease

Ebola hemorrhagic fever is a severe, often-fatal disease caused by infection with a species of Ebolavirus. Although the disease is rare, it can spread from person to person, especially among health care staff and other people who have close contact* with an infected person. Ebola is spread through direct contact with blood or body fluids (such as saliva or urine) of an infected person or animal or through contact with objects that have been contaminated with the blood or other body fluids of an infected person.

The likelihood of contracting Ebola is extremely low unless a person has direct contact with the body fluids of a person or animal that is infected and showing symptoms. A fever in a person who has traveled to or lived in an area where Ebola is present is likely to be caused by a more common infectious disease, but the person would need to be evaluated by a health care provider to be sure.

The incubation period for Ebola ranges from 2 to 21 days. Early symptoms include sudden fever, chills, and muscle aches. Around the fifth day, a skin rash can occur. Nausea, vomiting, chest pain, sore throat, abdominal pain, and diarrhea may follow. Symptoms become increasingly severe and may include jaundice (yellow skin), severe weight loss, mental confusion, shock, and multi-organ failure.

The prevention of Ebola virus infection includes measures to avoid contact with blood and body fluids of infected individuals and with objects contaminated with these fluids (e.g., syringes).

Management of ill people on aircraft if Ebola virus is suspected

Crew members on a flight with a passenger or other crew member who is ill with a fever, jaundice, or bleeding and who is traveling from or has recently been in a risk area should follow these precautions:

- Keep the sick person separated from others as much as possible.

- Provide the sick person with a surgical mask (if the passenger can tolerate wearing one) to reduce the number of droplets expelled into the air by talking, sneezing, or coughing.

- Tissues can be given to those who cannot tolerate a mask.

- Personnel should wear impermeable disposable gloves for direct contact with blood or other body fluids.

- The captain of an airliner bound for the United States is required by law to report to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) any ill passengers who meet specified criteria. The ill passenger should be reported before arrival or as soon as the illness is noted. CDC staff can be consulted to assist in evaluating an ill traveler, provide recommendations, and answer questions about reporting requirements; however, reporting to CDC does not replace usual company procedures for in-flight medical consultation or obtaining medical assistance.

General Infection Control Precautions

Personnel should always follow basic infection control precautions to protect against any type of infectious disease.

What to do if you think you have been exposed

Any person who thinks he or she has been exposed to Ebola virus either through travel, assisting an ill passenger, handling a contaminated object, or cleaning a contaminated aircraft should take the following precautions:

- Notify your employer immediately.

- Monitor your health for 21 days. Watch for fever (temperature of 101°F/38.3°C or higher), chills, muscle aches, rash, and other symptoms consistent with Ebola.

When to see a health care provider

- If you develop sudden fever, chills, muscle aches, rash, or other symptoms consistent with Ebola, you should seek immediate medical attention.

- Before visiting a health care provider, alert the clinic or emergency room in advance about your possible exposure to Ebola virus so that arrangements can be made to prevent spreading it to others.

- When traveling to a health care provider, limit contact with other people. Avoid all other travel.

- If you are located abroad, contact your employer for help with locating a health care provider. The U.S. embassy or consulate in the country where you are located can also provide names and addresses of local physicians

.

(Continue . . . )

As you can see, the CDC (and ECDC) response to these sorts of exposures is far less draconian than movies and TV might lead one to assume. Awareness and self monitoring for symptoms, not automatic quarantine, is the norm.

Although considered a low probability event, with millions of airline passengers every year, and an incubation period up to three weeks - it isn’t inconceivable for Ebola (or other viral hemorrhagic fever) to board an airplane undetected.

After all, over the past decade we’ve seen three cases of Lassa fever imported in the United States (see Minnesota: Rare Imported Case Of Lassa Fever).

The bottom line is that we ignore global healthcare and infectious disease outbreaks – even in the remotest areas of the world – at our own peril. Vast oceans and extended travel times no longer offer us protection. There are no technological shields that we can erect that would keep viruses like Ebola, MERS-CoV, or pandemic influenza from finding their way to our shores.

Which makes the funding and support of international public health initiatives, animal health initiatives, and disease surveillance ever so important, no matter where on this globe you happen to live.