H5N8 – A long way from home

# 9354

A week ago – when there was but one outbreak (in Germany) of HPAI H5N8 in Europe – the ECDC issued a Rapid Risk Assessment for EU Countries, noting that:

The public health threat from this event is considered very low. To date, no human infections with this virus have ever been reported world-wide and the risk for zoonotic transmission to the general public in the EU/EEA countries is considered to be extremely low.

While that basic public health assessment has not changed, the situation on the ground has.

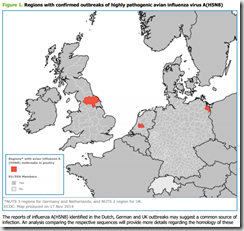

Since then there have been at least three more H5 or H5N8 outbreaks reported in European poultry, with the latest being a second farm in the Netherlands today. While we await confirmation that this latest outbreak is the same subtype as the others, the ECDC has published an updated Risk Assessment.

The entire PDF is 7 pages in length, and so I’ve only reproduced portions below. Click the link to download the entire report:

RAPID RISK ASSESSMENT

Outbreaks of highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N8) in Europe

Updated 20 November 2014

(EXCERPTS)

ECDC threat assessment for the EU

To date, no human infections with this virus have ever been reported worldwide and the risk of zoonotic transmission to the general public in EU/EEA countries is considered to be extremely low. However, this event is another indication of the widespread circulation and continuous re-assortment of avian influenza viruses, and specifically H5 viruses in animal populations, which continues to pose a long-term risk of human influenza

pandemics.

Investigations in the countries concerned have been initiated to determine how the virus entered the affected holdings. Germany reported that no live poultry or poultry meat from the affected holding has been shipped to other regions of Germany, other EU Member States or third countries. To date, there is no epidemiological evidence that avian influenza can be transmitted to humans through the consumption of cooked food, notably poultry meat and eggs.

The German reference laboratory for avian influenza viruses reported that the virus is detectable using EU recommended laboratory methods (M 1.2 and H5). However, further adjustments of these methods could still improve performance. Optimising test performance in the context of the newly emerged strain can enhance test sensitivity when supporting outbreak investigations. This needs to be balanced against broad sensitivity of assays for application in wider passive and active surveillance programmes where the virus subtype(s) is unknown.

The National Influenza Centres are assessing whether the available validated assays are sufficiently sensitive for detection of the A(H5N8) viruses in humans and they should be contacted if there is suspicion of human infection.

In order to prevent virus spread, Directive 2005/94/EC [12] requires that Member States have contingency ]plans detailing measures for the killing and safe disposal of infected poultry, feed and contaminated equipment as well as the procedures and methods for cleaning and disinfection. Reinforcing biosecurity measures to prevent contact between domestic poultry and wild birds is expected to reduce the risk of infection if wild birds are identified as a source of infection.

The Directive also requires the development of contingency plans for the control of avian influenza in poultry and birds in collaboration with public health and occupational health authorities to ensure that persons at risk are sufficiently protected from infection. Personal protective equipment, and in particular respiratory protection, should be considered. Persons at risk are mainly those in direct contact with/handling diseased birds and poultry, or their carcasses (e.g. farmers, veterinarians and labourers involved in the culling).

Vaccination with seasonal influenza vaccine is recommended for exposed workers having contact with birds and poultry to avoid the possibility of co-infection with human and avian influenza viruses and to reduce the risk of reassortment.

Persons in direct contact with infected poultry before or during culling and disposal, including poultry workers,

should be monitored for ten days, in order to document possible related influenza-like symptoms, fever or conjunctivitis. Local health authorities may consider actively monitoring these groups. Administration of antiviral prophylaxis for exposed persons as recommended for A(H5N1) can be considered as a precautionary measure depending on the local risk assessment (i.e. intensity of exposure) and in the context of the start of seasonal influenza in the EU to prevent reassortment [21].

Conclusions

There is wide diversity in the re-assorted avian influenza viruses circulating among wild bird populations across Asia. The ability of this highly pathogenic avian influenza virus to sub-clinically infect a broad range of wild birds increases the risk of geographical spread and subsequent outbreaks, as observed in South Korea. Therefore, ongoing monitoring and testing of wild birds and domestic poultry in the EU plays an important role in the detection of further virus incursion.It remains unclear how a highly pathogenic avian influenza virus A(H5N8) was simultaneously introduced into holdings in Germany, the Netherlands and the UK. The ongoing investigations into the transmission chain may provide important information for the prevention of further outbreaks in the EU.

It is important to remain vigilant, identify early transmission events to humans and ensure active surveillance of

exposed workers at the affected holdings for human health complaints, particularly during and after culling operations. As a minimum, exposed workers should be instructed to report health complaints (passive monitoring).