Credit ECDC

# 9824

Egypt is currently experiencing the largest outbreak of human H5N1 infections since the virus re-emerged in 2003, with roughly 115 cases reported over the past 17 weeks (see WHO H5N1 Update – Egypt).

While transmission still appears to be bird-to-human, and the virus remains difficult to spread from person-to-person, this uptick is nonetheless a worrisome development.

Today the ECDC has released one of their detailed Rapid Risk Assessments on Egypt’s recent H5N1 outbreak. First the summary, and then a link to, and excerpts from the document.

Rapid risk assessment: Human infection with avian influenza A(H5N1) virus, Egypt, first update

Available as PDF in the following languages

This document is free of charge.

Abstract

Human cases and fatalities due to influenza A(H5N1) virus continue to increase in Egypt, with cases from the country now accounting for the highest number of human cases reported worldwide.

Continuous increase of virus circulation in backyard poultry and exposure to infected poultry are most probably contributing to the increase in human cases. Whenever avian influenza viruses circulate in poultry, sporadic infections and small clusters of human cases are possible in people exposed to infected poultry or contaminated environments.

Although Egypt has reported an increased number of animal-to-human infections over the past few months, the influenza A(H5) viruses do not appear to transmit easily among people, and no sustained human-to-human transmission has been observed. As such, the risk of these viruses spreading in the community remains low.

Increased human infectivity of the circulating virus and the protection conferred by the poultry vaccines currently in use should be further investigated.

The current assessment remains that there is no risk for the general public in the EU. Travellers from the EU should avoid direct contact with poultry or poultry products when travelling to Egypt.

There is a low but ongoing and continuous risk of the virus being introduced and cases being imported into Europe and therefore both veterinary and public health authorities should maintain preparedness.

RAPID RISK ASSESSMENT Human infection with avian influenza A(H5N1) virus, Egypt

First update, 13 March 2015

ECDC threat assessment for the EU

Egypt has reported a dramatic increase in human cases and deaths due to A(H5N1) in recent months. During the same period, a large increase in outbreaks among poultry has been reported, mainly related to backyard farming. A(H5N1) affects all sectors of poultry production, is detected in different bird species and circulates in all geographical areas.

The reason for the current increase in human infections is believed to be the spread of the virus within the backyard poultry population and the intensive virus circulation. There has also been speculation that increased co circulation of A(H9N2) might have contributed to the intensified spread of A(H5N1) in poultry and associated human cases in Egypt. The current joint WHO/CDC/FAO/OIE mission to Egypt will hopefully provide more information on the reason for the sharp increase in human cases. A strategy needs to be established to prevent further geographical spread.

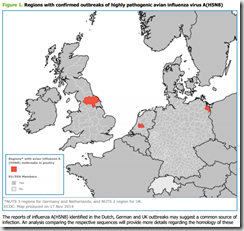

Although the risk of an introduction of A(H5N1) into Europe via migratory birds seems to be very low, the increase in the number of outbreaks and the higher level of virus circulation in the poultry population in Egypt might increase the likelihood for A(H5N1) infections of migratory birds. In particular, migratory waterfowl are known to be potential vectors for the introduction of A(H5N1) to free areas as they undertake movements at certain times of the year. Therefore in Europe there is a theoretical risk that the virus may spread to poultry and the veterinary sector should maintain vigilance, using well-established surveillance systems for early detection, should new introductions occur.

Whenever avian influenza viruses are circulating in poultry, sporadic infections and small clusters of human cases are possible in people exposed to infected poultry or contaminated environments. Although an increased number of animal-to-human infections has been reported by Egypt over the past few months, these influenza A(H5) viruses do not appear to transmit easily among people at present. As such, the risk of these viruses spreading in the community remains low.Human infections are related to exposure to infected poultry, with the increase in outbreaks among backyard poultry most probably contributing to the increase in human cases. Increased human infectivity of the circulating virus and protection conferred by the poultry vaccines currently in use should be further investigated. No indications of human–to-human transmission have been reported from Egypt. As such, the risk of these viruses spreading in the community remains low, and the assessment of the last ECDC Rapid Risk Assessment published on 23 December 2014 remains valid.

Although the areas where there has been transmission in poultry are mostly rural, the importation of a sporadic travel-related human A(H5N1) case into the EU is possible and public health authorities should be prepared. The risk of EU citizens being infected in Egypt is extremely low. No cases of A(H5N1) among travellers to Egypt have ever been notified. Travellers should be advised to avoid direct contact with poultry or poultry products.