Map Credit FAO

# 9399

Crof already has the story and the Canadian Government’s official statement (see Canada: Avian influenza confirmed on two farms in Fraser Valley). But the upshot is that over the weekend two Fraser Valley, British Columbia farms – roughly 25 miles apart – saw unusually high mortality in turkeys and broilers, and now both farms have tested positive for H5 avian flu.

The subtype – and whether this is HPAI or LPAI – has yet to be determined, but the high mortality rate of the birds suggests high pathogenicity.

This is the fourth significant outbreak of avian flu in the Fraser Valley region over the past decade, with the first being an H7N3 outbreak in 2004 that required the culling of 17 million birds, cost the Canadian economy tens of millions of dollars, and resulted in at least two mild human infections (see EID Journal report Human Illness from Avian Influenza H7N3, British Columbia)

The following year, an LPAI H5N2 outbreak occurred on a duck and goose farm in the same region. An OIE report entitled Avian influenza: the Canadian experience by J. Pasick, Y. Berhane & K. Hooper-McGrevy describes the impact of these two outbreaks.

In 2004, Canada reported its first case of HPAI to the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE). The outbreak, which began in a broiler breeder farm in the Fraser Valley of British Columbia, involved an H7N3 LPAI virus which underwent a sudden virulence shift to HPAI. More than 17 million birds were culled and CAN$380 million in gross economic costs incurred before the outbreak was eventually brought under control. In its aftermath a number of changes were implemented to mitigate the impact of any future HPAI outbreaks. These changes involved various aspects of avian influenza detection and control, including selfquarantine, biosecurity, surveillance, and laboratory testing.

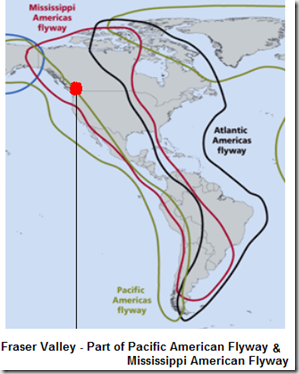

In 2005, a national surveillance programme for influenza A viruses in wild birds was initiated. Results of this survey provided evidence for wild birds as the likely source of an H5N2 LPAI outbreak that occurred in domestic ducks in the Fraser Valley in the autumn of 2005. Wild birds were once again implicated in an H7N3 HPAI outbreak involving a broiler breeder operation in Saskatchewan in 2007. Fortunately, both of these outbreaks were limited in extent, a consequence of some of the changes implemented in response to the 2004 British Columbia outbreak.

Two farms Abbotsford farms were hit again in 2009 with the LPAI H5N2 virus (see H5N2 Identified In Canadian Outbreak), although the impact of these H5 outbreaks was far less than that seen in 2004 with H7N3. There was another H7N3 outbreak in Saskatchewan, but compared to 2004, this was a fairly minor event as well.

From the conclusion of the above report, the authors write:

The occurrence of HPAI H7N3 in the Fraser Valley of British Columbia was Canada’s first reported outbreak to the OIE. It precipitated a number of changes from producer to federal government levels, dealing with issues ranging from self-quarantine to laboratory testing.

The association of viruses that were responsible for subsequent LPAI H5N2 and HPAI H7N3 outbreaks with those found circulating in wild birds stresses the importance of the latter as a continued source of infection and of biosecurity as a means of preventing exposure.

It will take a day or two before we know if this outbreak is a repeat of the H5N2 subtype that struck in 2005 and 2009, or if it is of a different subtype.