Live Bird Market in Hanoi – Credit FAO

#10,767

From The Lancet today we’ve an analysis by a literal Who’s Who of avian flu Virology on actions that could (read: should) be taken to curb the evolution and spread of avian flu in Asia. Below is a link to the Lancet report, which you can read in its entirety (a free registration is required), after which I’ll return with more.

Interventions to reduce zoonotic and pandemic risks from avian influenza in Asia

Prof J S Malik Peiris, DPhil

Benjamin J Cowling, PhD, Joseph T Wu, PhD, Luzhao Feng, MD, Prof Yi Guan, PhD, Dr Hongjie Yu, MD

, Prof Gabriel M Leung, MD

Published Online: 01 December 2015

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00502-2

Published Online: 01 December 2015

© 2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Summary

Novel influenza viruses continue to emerge, posing zoonotic and potentially pandemic threats, such as with avian influenza A H7N9. Although closure of live poultry markets (LPMs) in mainland China stopped H7N9 outbreaks temporarily, closures are difficult to sustain, in view of poultry production and marketing systems in China.

In this Personal View, we summarise interventions taken in mainland China, and provide evidence for other more sustainable but effective interventions in the live poultry market systems that reduce risk of zoonotic influenza including rest days, and banning live poultry in markets overnight. Separation of live ducks and geese from land-based (ie, non-aquatic) poultry in LPM systems can reduce the risk of emergence of zoonotic and epizootic viruses at source.

In view of evidence that H7N9 is now endemic in over half of the provinces in mainland China and will continue to cause recurrent zoonotic disease in the winter months, such interventions should receive high priority in China and other Asian countries at risk of H7N9 through cross-border poultry movements. Such generic measures are likely to reduce known and future threats of zoonotic influenza.

While their abstract targets H7N9 - which is currently the most worrisome avian flu virus in Asia – this analysis notes the importance of creating generic interventions that would work against a variety of emerging zoonotic threats.

The closing all live bird markets would go a long ways towards reducing the risks (see The Lancet: Poultry Market Closure Effect On H7N9 Transmission), but China, Indonesia, Egypt, and many other Asian nations have run into considerable public resistance to the idea.

In 2009, we saw China Announce A Plan To Shut Down Live Poultry Markets In Many Cities, yet nearly 7 years later most still operate (legally or illegally).

In recent years we’ve seen the emergence – and reassortment – of a number of novel viruses in China including H5N8, H5N6, H10N8, and just recently H5N9. The authors warn the common practice of keeping waterfowl (ducks & geese) together with terrestrial birds (chickens, quail, etc.) only increases the odds of creating new reassortant viruses.

Reassorted viruses can result when two different flu strains inhabit the same host (human, swine, avian, or otherwise) at the same time. Under the right conditions, they can swap one or more gene segments and produce a new, hybrid virus.

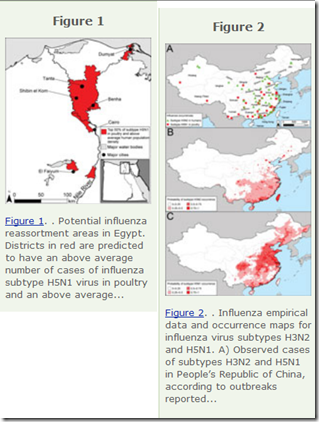

And while emerging or reassorted pandemic threats can emerge from anywhere in the world, China has been the most prolific producer of novel flu viruses in modern times. In the spring of 2013 – just two weeks before the new reassorted H7N9 virus was announced in Shanghai – the CDC’s EID Journal carried an analysis on those areas of the world most likely to produce new reassortant viruses.

In EID Journal: Predicting Hotspots for Influenza Virus Reassortment, we looked at this study which identified 6 key geographic regions where reassortments are likely to emerge. And high on that list (you guessed it), is Eastern mainland China.

Potential geographic foci of reassortment include the northern plains of India, coastal and central provinces of China, the western Korean Peninsula and southwestern Japan in Asia, and the Nile Delta in Egypt.

The authors conclude by writing:

The potential for reassortment between human and avian influenza viruses underscores the value of a One Health approach that recognizes that emerging diseases arise at the convergence of the human and animal domains (29,40).

Although our analysis focused on the influenza virus, our modeling framework can be generalized to characterize other potential emerging infectious diseases at the human–animal interface.

The unanswered $64 question is whether China (and many other countries) can find the political will to make these types of needed changes before the next pandemic-ready virus emerges.