#12,276

Flu viruses are, by their very nature, moving targets. In order to survive, they must change antigenically over time in order to evade acquired and accrued immunity in their host species. Without continual evolution, a virus as contagious as influenza would quickly run out of susceptible hosts and die out.

It is for this reason the flu shot must be updated periodically, and why we often see multiple versions (clades, subclades, or genotypes) of the same influenza subtype in circulation around the world.And just as there are currently more than a half dozen subclades of seasonal H3N2 jockeying for dominance in the flu world (see last November's ECDC Influenza Virus Characterization Report), there are dozens of subclades and genotypes of avian and swine flu viruses competing in the wild.

Simply put, the H5N1 virus in Egypt (Clade 2.2.1.2) isn't isn't the same as the H5N1 virus in Nigeria (Clade 2.3.2.1c), or the one in Bangladesh (Clade 2.3.2.1a).

So, when we speak of the avian H5N1 virus, or H7N9 - we are really talking about multiple genetically distinct variants - each on their own evolutionary path. And a vaccine developed against one strain of the same subtype may not prove protective against another.

Since it can take months to craft and manufacture an emergency vaccine against a novel virus, the WHO - in corroboration with other agencies - attempts to identify those viruses emerging in the wild which may pose a human health threat, and make recommendations for new candidate vaccine viruses (CVVs).

In 2015, we looked at a primer on the process in CDC: Making a Candidate Vaccine Virus For HPAI Avian Flu. While it can be expensive, having a proven Candidate Vaccine Virus already tested and approved can save months of valuable time if mass production and distribution of a vaccine is ever required.

Complicating matters, we have more novel viruses in the wild now than we've ever seen before, and their diversity continues to grow. Today the WHO has published a 15 page review of novel viruses in the wild, and their recommendations for new CVVs.

Due to its length I've only excerpted a few passages. Follow the link to read the entire document.

Antigenic and genetic characteristics of zoonotic influenza viruses and development of candidate vaccine viruses for pandemic preparedness

March 2017

The development of candidate influenza vaccine viruses (CVVs), coordinated by the World Health Organization (WHO), remains an essential component of the overall global strategy for influenza pandemic preparedness.

Selection and development of CVVs are the first steps towards timely vaccine production and do not imply a recommendation for initiating manufacture. National authorities may consider the use of one or more of these CVVs for pilot lot vaccine production, clinical trials and other pandemic preparedness purposes based on their assessment of public health risk and need.

Zoonotic influenza viruses continue to be identified and evolve both genetically and antigenically, leading to the need for additional CVVs for pandemic preparedness purposes.(Continue . . . )

Changes in the genetic and antigenic characteristics of these viruses relative to existing CVVs, and their potential risks to public health, justify the need to select and develop new CVVs.

This document summarizes the genetic and antigenic characteristics of recent zoonotic influenza viruses and related viruses circulating in animals1 that are relevant to CVV updates. Institutions interested in receiving these CVVs should contact WHO at gisrs-whohq@who.int or the institutions listed in announcements published on the WHO website2.

The H5 viruses - which have been in circulation longest - have seen 32 CVVs developed since 2004, with 4 additional candidate vaccines already in the pipeline, and 1 new recommendation; A/duck/Hyogo/1/2016-like (H5N6)

Remarkably, in less than 14 years the continual evolution of H5 avian viruses has forced the creation and development of more than 3 dozen CVVs. As these viruses (H5N1, H5N6, H5N8, etc.) continue to spread, additional CVVs will no doubt be needed.

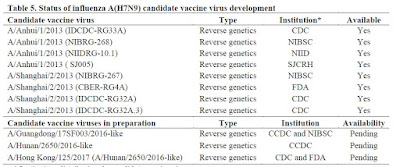

H7N9 - which only emerged in 2013 - has far fewer CVVs, with 8 already available, and 3 new recommendations since last September's report (see chart below).

The recent revelation of an HPAI lineage of H7N9 emerging in Guangdong Province (see ECDC Comment On HPAI Mutation Of H7N9) is the most dramatic change we've seen in the virus. The WHO report states:

A(H7N9) viruses of the YRD lineage with multiple basic amino acids at the cleavage site have been detected in humans, poultry and environmental samples from live poultry markets. These viruses fulfil the requirements for classification as HPAI viruses. The HPAI A(H7N9) viruses were genetically and antigenically distinct from other A(H7N9) viruses including A/Hunan/2650/2016 and the current CVVs (Figure 2, Table 3 and 4). Therefore, a new CVV derived from an A/Guangdong/17SF003/2016-like virus (HPAI) is proposed.The implications of this new H7N9 lineage are well discussed in Helen Branswell's report yesterday in Stat : As bird flu spreads, US concludes its vaccine doesn’t provide adequate protection.

On the H1N1 swine flu front, the WHO is recommending two new CVVs generated from swine variant A/Iowa/32/2016 and A/Netherlands/3315/2016-like viruses.

While no new swine variant H3N2 viruses are recommended, there is one still in the pipeline (A/Ohio/28/2016-like), which emerged late last summer in an outbreak in Michigan and Ohio, infecting 18 people who were exposed at local agricultural fairs.

In October (see MMWR: Investigation Into H3N2v Outbreak In Ohio & Michigan - Summer 2016) we learned that 16 of the 18 cases analyzed belonged to a new genotype not previously detected in humans.

The reality is that unless and until an effective universal vaccine can be developed, we are always going to be playing catch-up with a very nimble viral foe.