|

| Credit DEFRA |

#12,555

Compared to much of the rest of Western Europe, the UK - with just 10 poultry outbreaks - got off relatively easy during this past winter's record setting avian epizootic of HPAI H5N8. Across the Channel, France recorded nearly 500.

With migratory birds viewed as the main culprit in spreading this recently reassorted virus (and its spinoffs, like H5N5), and the first arrivals of next fall's migratory birds expected in September, it is important to dissect and understand the patterns of HPAI H5's spread during this past winter.To that end, DEFRA's ( Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs) Animal & Plant Health Agency has published a detailed, 50-page post mortem of last winter's outbreaks in the UK. Some excerpts from this report follow:

National epidemiology reportSituation at 16:00 on Tuesday 2 May 2017

Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H5N8: December 2016 to March 2017

Executive summary

The initial phase of the 2016-2017 outbreak of H5N8 highly pathogenic avian influenza in the UK consisted of ten infected premises, distributed across six distinct geographical areas of England and Wales: Lincolnshire, Lancashire, Suffolk, Carmarthenshire, Yorkshire and Northumberland.

Three of the outbreaks, in Carmarthenshire, Yorkshire and Northumberland were on single smallholder premises. The three infected premises (IPs) in Lincolnshire were engaged in turkey production and the three infected premises in Lancashire were involved in gamebird production; and were all associated with one business enterprise. The single premises in Suffolk was a broiler breeder unit involved in the production of chickens for meat.

This report has been arranged in sections devoted to individual geographical clusters, which coincidentally also correspond to different production systems. The three smallholder premises are described as a production system cluster, although these outbreaks were not connected in any way, and the premises are widely distributed across the country.

All the outbreaks, apart from those at the game bird premises in Lancashire, are considered to have arisen as independent events, resulting from direct or indirect primary incursions from wild birds. The IPs in Lancashire are considered to have originated as the result of a direct or indirect primary incursion of HPAI H5N8 from wild birds, with subsequent spread between related premises, taking place as a result of business activities.

Extensive epidemiological investigations did not detect the presence of infection in any further premises investigated in connection with the IPs, either by known contacts (source and spread tracings), or as a result of proximity (protection and surveillance zones).

though the epidemiological investigation concludes that the most likely route of introduction of virus onto the majority of the IPs was direct or indirect contact with wild birds, an incursion such as these, onto an individual premises, remains a low likelihood event and is largely influenced by the effectiveness of biosecurity measures that have been implemented.

(SNIP)

International context

In late October 2016, H5N8 HPAI was first detected in the Eastern EU in wild birds and poultry and, given the migration patterns of wild migratory waterfowl, the risk level to the UK was increased from low to medium on the 11th November.

In mid-November, wild bird cases were detected in western EU Member States and on the 1st December the risk for incursions to poultry was raised to low but heightened. Outbreaks in poultry and findings in wild birds continued over the coming months in most Member States as well as neighbouring countries in the Middle East, North Africa and East Europe.

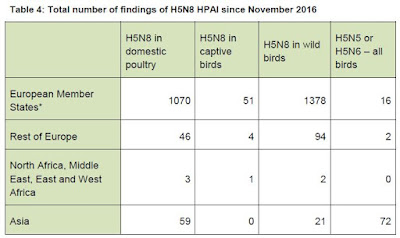

To date, over a thousand poultry outbreaks have been reported and nearly 1,500 wild bird findings (see Table 4 below). This is an unprecedented level of highly pathogenic avian influenza, even more so than the epizootic of H5N1 HPAI in 2005-6.

The wider range of wild bird species (including gulls, birds of prey and a small number of corvids) and high pathogenicity were also unusual and the risk level for the UK was such for a wild bird incursion that the CVO put in place an Avian Influenza Prevention Zone on the 7th December and this is still in place. Under this order, poultry keepers must take all possible provisions to prevent wild bird contact and the risk level for poultry was raised to low to medium.

Sequence data suggests there have been two incursions into Europe, one across Central Europe from Hungary and as far as SW France, while the other route encompasses the Baltic region and NW Europe including the UK.

Table 4: Total number of findings of H5N8 HPAI since November 2016

(Continue . . . )

Via genetic analysis (see EID Journal: Reassorted HPAI H5N8 Clade 2.3.4.4. - Germany 2016) we now know that the H5N8 virus that arrived this past fall was a novel reassortment - having picked up genetic contributions from other avian viruses (probably in Russia or China) last summer.

The virus that showed up 8 months ago was more virulent, and appears to be more easily carried and transmitted by birds, than the H5N8 virus that showed up in North America and Europe two years before.Although the virus continues to circulate at low levels in wild birds in Europe this summer (see Belgium Reports More Outbreaks Of H5N8), the big unknown is what the virus is doing in the summer roosting regions of Siberia or the Arctic, and what (if anything) returns with migratory birds next fall.