#12,968

Nearly every year we see a handful of tragic deaths – mostly of children – due to an almost always fatal condition called PAM (Primary amebic meningoencephalitis), caused by a brain infection from an amoebic parasite called Naegleria fowleri.

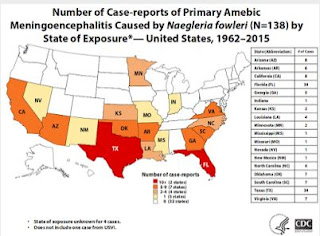

Dubbed the `brain eating amoeba' by the press, this parasite enters the brain through the nasal passages, usually due to the forceful aspiration of water (containing the amoeba) into the nose.Naegleria, as a thermophilic (heat-loving), free-living amoeba, is most often encountered while swimming in warm, stagnant, fresh water ponds and lakes. It is hardly surprising to see that Florida and Texas (see chart above) lead the nation in cases over the past three decades, although infections have occurred as far north as Minnesota.

Until a few years ago, nearly all of the Naegleria infections reported in the United States were linked to fresh water swimming (see Naegleria: Rare, 99% Fatal & Preventable), making this pretty much a summer time threat.In 2011, however, we saw two cases reported in Neti pot users from Louisiana, prompting the Louisiana Health Department to recommend that people `use distilled, sterile or previously boiled water to make up the irrigation solution’ (see Neti Pots & Naegleria Fowleri).

Unusually, in 2013 we also saw a 4 year-old infected through contact with a municipal water supply while visiting St. Bernard Parish, Louisiana. Since then testing has revealed Naegleria in a number of municipal water supplies across the state of Louisiana (see Louisiana: 2nd Public Water System Reports Naegleria).

And last year we looked at an MMWR: Epidemiological Investigation Into A Case Of Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis in California which suggested a poorly chlorinated spring-fed swimming pool was the likely source of infection and death of a 21 year old woman.

While most years only 2 to 4 cases are reported in the United States, the actual number of infections is unknown. The symptoms are clinically similar to bacterial meningitis, and as the disease usually progresses rapidly, diagnosis can be difficult.Up until a recently, infection with Naegleria fowleri was universally fatal, but in 2013 an investigational drug called miltefosine was used successfully for the first time to treat the infection. To date, 3 children treated with miltefosine have survived, although one reportedly sustained permanent neurological damage.

The availability of a treatment raises the stakes considerably, making early diagnosis and early administration of this drug absolutely critical.Based on the following research letter written by epidemiologists from the CDC, the average number of PAM cases in the United States probably averages closer to 16 (8 males, 8 females) each year, meaning that right now, 70%-80% likely go unrecognized.

Volume 24, Number 1—January 2018For some of my earlier blogs on Naegleria, you may wish to revisit:

Research Letter

Estimation of Undiagnosed Naegleria fowleri Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis, United States

Almea Matanock, Jason M. Mehal, Lindy Liu, Diana M. Blau, and Jennifer R. Cope

Author affiliations: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA

Abstract

Primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM) is an acute, rare, typically fatal disease. We used epidemiologic risk factors and multiple cause-of-death mortality data to estimate the number of deaths that fit the typical pattern for PAM; we estimated an annual average of 16 deaths (8 male, 8 female) in the United States.

Naegleria fowleri causes primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM); 0–8 laboratory confirmed cases per year are documented in the United States) (1). PAM causes < 0.5% of diagnosed encephalitis deaths in the US (2). Laboratory-confirmed PAM case-patients in the United States are a median age of 12 years and are identified primarily in southern states during July–September, and 79% are male (1,3). Many case-patients are identified post-mortem; 4 known survivors have been reported in the United States (1,4).

The signs and symptoms of PAM can be mistaken for other more common neuroinfections, such as bacterial meningitis and viral encephalitis (1,4). Because more than half of neuroinfectious deaths are unspecified (2), clinical expertise and diagnostic testing availability are limited, and true PAM incidence is unknown, and concern is reasonable that PAM cases might not be diagnosed. In this study, we estimate the magnitude of potentially undiagnosed cases of PAM by applying previously identified epidemiologic risk factors to unspecified neuroinfectious deaths.

(SNIP)

Although all available evidence points to PAM being a low-incidence disease in the United States, PAM remains a devastating and nearly universally fatal infection that erodes public confidence in the safety of everyday activities (swimming, using public drinking water) and increased stress on local public health departments that are already overextended. The reports of recent survivors indicate that timely diagnosis and early initiation of anti-amebic therapy may be instrumental in combatting this deadly infection (4). Therefore awareness, evaluation of risk factors, testing, and early anti-amebic therapy provide the best opportunity for survival (1).

Dr. Matanock was an Epidemic Intelligence Service Officer in the Waterborne Disease Prevention Branch, Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA at the time of this project and is now an epidemiologist in the Respiratory Diseases Branch, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC. Her research interests include disease detection and surveillance.

A Reminder About Naegleria

Reminder: COCA Call Today On Naegleria Fowleri & Cryptosporidium

Amoeba Summit 2015