# 2419

Most people by now know that there were 3 pandemics in the last century; the 1918 Spanish Flu, the 1957 Asian Flu, and the 1968 Hong Kong Flu.

But many people are unaware of the no-name influenza epidemic of 1951, or of the Pseudopandemics of 1947 and (in children) of 1977.

The no-name epidemic of 1951 was one that, for a few weeks - mostly in England and Canada- proved to be deadlier than the 1918 Spanish Flu.

Between 1918, and 1957, the dominant (and likely, only) influenza strains circulating in humans were H1N1 variants. These variants were descendent from the 1918 Spanish Flu.

Some years the flu was more virulent than others.

This first graph shows the excess P&I (pneumonia & Influenza) deaths as recorded in 35 large cities across America between 1910 and 1921.

(click on graphs to enlarge)

(Next 3 graphs from Influenza in the United States, 1887-1956)

The 1918 and 1919 waves of the Spanish flu are readily apparent.

Over the next decade, however, the United States continued to see spikes in mortality rates, indicating a virulent seasonal flu still circulating.

The 1922, 1923, 1925, and 1928 spikes are well above the baseline.

It should be noted that these graphs utilize a different scale, and the peak P&I rates indicated in 1928 are less than half that of 1918.

After 1930, and for the next 25 years (until 1957, actually), the United States would see very few severe flu seasons. One exception would be 1947.

In 1946-47, what would later be described as the Pseudopandemic of 1947 erupted. First detected on US military bases in Japan in 1946, it quickly spread around the world.

The existing flu shots, in use since 1943, proved useless against this new strain. While still H1N1, there had been a sudden and significant antigenic shift, creating a complete failure of the vaccine that year.

1947 is little remembered today, except by epidemiologists, because while widespread, this new flu strain produced few excess deaths.

While we worry that a novel strain of influenza will come out of the wild and spark a pandemic, there exists another possibility:

That an existing strain will drift or shift (two different concepts) into a new subtype of influenza, one capable of causing a pandemic.

That is apparently what happened in 1947. The existing H1N1 virus experienced a sudden antigenic change, making people susceptible to infection, and nullifying the existing vaccine.

Had this change also produced a particularly virulent (pathogenic) strain, 1947 could have become another pandemic year.

In other words, when the genetic dice were rolled in 1946, the human race got very, very lucky.

For many people in England, Wales, and Canada - 1951 would be a year where their luck ran out.

For most of the world, 1951 remained an average flu year. The dominate strain of influenza that year was the so-called `Scandinavian strain', which produced mild illness in most of its victims.

In fact, if you look at the graph for the United States, running from 1945 to 1956, you'll see nary a blip.

But in December of 1950 a new strain of virulent influenza appeared in Liverpool, England, and by the end of the flu season, had spread across much of England, Wales, and Canada.

The CDC's Journal of Emerging Infectious Disease has a stellar account of the 1951 epidemic, and much of what follows I've gleaned from this report:

Viboud C, Tam T, Fleming D, Miller MA, Simonsen L. 1951 influenza epidemic, England and Wales, Canada, and the United States. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2006 Apr [date cited]. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/...

According to this study, the effects on the city of origin, Liverpool, were horrendous.

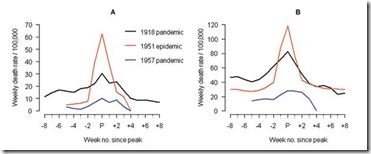

In Liverpool, where the epidemic was said to originate, it was "the cause of the highest weekly death toll, apart from aerial bombardment, in the city's vital statistics records, since the great cholera epidemic of 1849" (5). This weekly death toll even surpassed that of the 1918 influenza pandemic (Figure 1)

This extraordinary graph shows the excess deaths in Liverpool during this outbreak (red line), while the black line shows the peak deaths during the 1918 pandemic. This chart shows excess deaths by A) respiratory causes (pneumonia, influenza and bronchitis) and B) all causes.

For roughly 5 weeks Liverpool saw an incredible spike in deaths due to this new influenza. And it did not remain just in Liverpool. While it appears not to have spread as easily as the dominant Scandinavian strain, it managed to infect large areas of England, Wales, and Canada over the ensuing months.

The authors of this study describe the spread of this new influenza:

Geographic and Temporal Spread

Influenza activity started to increase in Liverpool, England, in late December 1950 (5,13). The weekly death rate reached a peak in mid-January 1951 that was ≈40% higher than the peak of the 1918–19 pandemic, reflecting a rapid and unprecedented increase in deaths, which lasted for ≈5 weeks [5 ] and Figure 1).

Since the early 20th century, the geographic spread of influenza could be followed across England from the weekly influenza mortality statistics in the country's largest cities, which represented half of the British population (13). During January 1951, the epidemic spread within 2 to 3 weeks from Liverpool throughout the rest of the country.

For Canada, the first report of influenza illness came the third week of January from Grand Falls, Newfoundland (19). Within a week, the epidemic had reached the eastern provinces, and influenza subsequently spread rapidly westward (19).

For the United States, substantial increases in influenza illness and excess deaths were reported in New England from February to April 1951, at a level unprecedented since the severe 1943-44 influenza season. Much milder epidemics occurred later in the spring elsewhere in the country (9).

Perhaps most telling is this graph showing the death rates in England and Wales between 1950 and 1971, which incorporates the no-name outbreak of 1951, and the 1957 and 1968 pandemics. As you can see, the 1951 event was more severe than either of the two `official' pandemics.

Crude death rates (blue bars), death rates adjusted for summer trends in mortality unrelated to influenza (pink bars)

For reasons we don't understand, this new strain never managed to spread much beyond England, Wales, and Canada. It did not reappear the next flu season either. It vanished as mysteriously as it appeared.

To this litany of outbreaks, we could also add the re-emergence of the H1N1 virus in 1977, the so-called Russian Flu. After being driven out of circulation in 1957 by the H2N2 Asian Flu, H1N1 was virtually unheard of outside of a laboratory setting until 1977.

There is speculation, in fact, that it's reappearance wasn't a natural occurrence, but rather that it came from an accidental release from a laboratory in the Soviet Union.

In any event, 1977 was a particularly bad flu year, particularly for those under the age of 25, who had never been exposed to the H1N1 virus. 1977 could probably be classified as a Pseudopandemic year like 1947.

Since then, the H1N1 virus has co-existed with the H3N2 virus, both circulating each flu season, with neither dominant enough to eliminate the other.

The point of all of this is that pandemics, and epidemics, actually happen more often than most people think. To the 1918, 1957, and 1968 pandemics of the last century, we could also easily add 1947, 1951, and 1977 as `close calls'.

And of course, the most famous close call of all was the 1976 Swine Flu scare. Since I was a working medic during that time, I've written about it several times, including here and here.

If you go back 300 years, you'll find at least 10 influenza pandemics have occurred. And that doesn't count pseudopandemic years.

Influenza viruses are continually mutating.

Most of the mutations (of which billions occur each day) are evolutionary dead-ends. But every once in awhile, the virus hits the jackpot, and a new highly infectious and virulent strain appears.

There is nothing currently in our medical arsenal to to prevent this from happening, or to protect us when it does. We remain as vulnerable to influenza pandemics today as we have always been.

Our only real advantage (other than some antivirals and antibiotics) over our parents and grandparents generation is that we may be able to see the next pandemic coming, before it gets here.

Through surveillance, and laboratory tests, we may detect a pandemic strain days, weeks, even months before it arrives.

We may be seeing such a virus in the H5N1 bird flu strain. But of course, the next pandemic could come at us right out of the blue.

Which is why we must prepare now. Before the next pandemic strikes.

Because, as history reminds us, another one will.