# 3570

Roughly 7 weeks into the pandemic of 2009 (declared June 11th), we find ourselves with a surprisingly low number of `confirmed flu deaths’, and a lot of important unanswered questions.

The official numbers we get from the CDC, the WHO, and from individual countries are almost always referred to as `the tip of the iceberg’, or as in the graphic below, the tip of the pyramid.

Here in the US the CDC openly admits to there having probably been at least a million infections across the country, not the 43,000+ which was the last count a week or so ago.

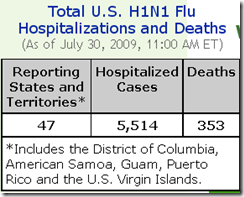

As of this week, the CDC is no longer counting the number infected, but continues to provide numbers on hospitalizations and confirmed deaths.

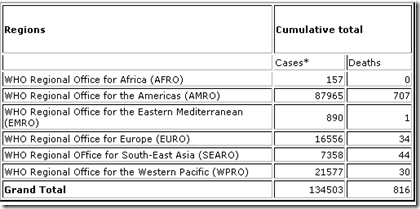

The WHO (World Health Organization) has cut back on its reporting as well, simply because the `numbers’ they have make very little sense. At last report (July 27th) the worldwide number of infections was less than 20% of the CDC’s estimate for the US alone.

While just about everyone accepts that the number of infected greatly outpace the official numbers, most people seem willing to accept the `official deaths’ number as being reasonably accurate.

There are reasons, however, to question that number as well.

The CFR, or case fatality ratio of a pandemic is generally seen as the most important statistic of a pandemic, and yet it is often the hardest to quantify. The CFR is essentially the percentage of people who, once infected, die (either directly or indirectly) as a result of that infection.

If 1,000 people are infected, and 1 dies the CFR is .1%. If 2 people out of 1,000 die the CFR is .2%. And if 10 people out of 1,000 die the CFR is 1.0%.

The great pandemic of 1918 killed roughly 25 Americans for every 1,000 it infected, giving a CFR of 2.5%. Seasonal flu, on the other hand, is believed to kill roughly 1 person in 1,000; or a CFR of .1%.

But that number is subject to considerable debate.

The problem is, everything we are using as a baseline for seasonal flu is predicated on complex estimates, mathematical models, and no small amount of (educated) guesswork.

We aren’t counting individual death certificates to come up with the oft quoted “36,000 Americans die each year from flu’ statistic.

The truth is, that number is based on mathematical models that looked at excess deaths during flu seasons over a multi-year period. That range of excess deaths ran from 17,000 to 52,000 during the decade of the 1990s.

We know that during the fall and winter the number of deaths jumps for a number of causes. Heart attacks, respiratory distress, pneumonia, along with other so called `natural causes’ . . . and that these jumps in deaths often coincide with or follow the rise in influenza cases each year.

While it may not always be possible to know on a case-by-case basis if influenza was a direct (or even indirect) cause of death, statistically there is pretty good data to suggest that it at least contributes to tens of thousands of deaths each year.

The problem is, influenza can provoke or exacerbate other medical problems. Influenza can obviously lead to pneumonia and death, but it has also been linked to heart attacks and even strokes (CVAs), and no doubt exacerbates other medical conditions as well.

In other words, influenza probably `silently’ contributes to a lot more deaths than are first apparent.

Elderly persons, bedridden for a week with the flu, may throw a clot and die of a PE (Pulmonary embolism) or a stroke. Vomiting and diarrhea can cause life threatening dehydration.

There are a lot of ways influenza can contribute to someone’s death.

The only way to pick up on these deaths is statistically, since most of the victim’s death certificates say `CVA’ or `Coronary Artery Disease’ or `Myocardial Infarction’.

In the United States each day, roughly 6,000 people die; mostly from `natural causes’. Only in cases of trauma, misadventure, or other suspicious circumstance is an autopsy done. And even if that happens, testing for influenza isn’t normally done.

Most of the time, the attending doctor signs the death certificate and puts down the most immediate or obvious cause of death. If influenza was a factor, it rarely is noticed or noted.

Since we are unable to track with specificity the deaths from influenza during our regular flu season, why do we think we can do so with this novel virus?

Today out of Tasmania, we get this article regarding 4 recent swine flu deaths that I think illustrates the problem.

Girl dies of swine flu

NICK CLARK

August 01, 2009 02:00am

A YOUNG North-West Coast girl has become the fourth Tasmanian killed by swine flu.

The girl, believed to be 11, died suddenly last week, said public health acting director Chrissie Pickin.

"While initial testing for Influenza A and H1N1 had returned negative results, a tissue sample sent to Melbourne for laboratory testing had revealed the girl was in fact suffering H1N1," Dr Pickin said.

On Tuesday a 38-year-old northern Tasmanian woman with swine flu died from a cardiac arrest. Other victims have been a 77-year-old from the North-West and an 85-year-old from Sandy Bay.

Dr Pickin said some testing being used was not sensitive enough to detect the virus.

It is winter, and flu season in Tasmania (pop. 500K), and so flu deaths are to be expected. This year we are watching closely to see how the novel H1N1 virus affects them.

(Note: 50% of these reported deaths are, unusually for novel H1N1, among the elderly. While this is too small a sample to draw any conclusions from, this is something to watch).

Four deaths, out of a population of 500,000 – while always tragic – isn’t very many.

But as this article points out, the tests being used to screen for the virus aren’t very sensitive. The RIDT (Rapid Influenza Diagnostic Tests) are notoriously insensitive, with failure to detect (false negative) rates as high as 50%.

Which means that a negative test tells you very little.

The CDC released guidance on the interpretation of negative RIDT results earlier this week, and it includes:

So the failure to detect the virus in the 11 year old girl is certainly no surprise. It happens a lot. And unless the patients symptoms are unusually severe, additional testing is rarely done.

Authorities did extra testing to determine this unfortunate girl’s cause of death because of her age. I’m not as confident that they would have bothered for a 65 year old man who died suddenly from what might have appeared to have been a heart attack.

The deaths we hear about are only `laboratory confirmed’ deaths. And most of these are occurring in a hospital setting.

Our surveillance, and the surveillance in most of the industrialized world, simply isn’t up to detecting and reporting on individual flu-related deaths. And in developing countries, surveillance is undoubtedly even less reliable.

The numbers we get don’t make a lot of sense right now, and perhaps they never will.

If we’ve really had a million infections in this country (and I suspect that is low), and if this virus were as virulent as we believe seasonal flu to be (CFR .1%), then we should have seen 1,000 deaths so far – not 352.

And my guess is, we probably have.

Our surveillance system is simply unable to count them. Just like we can’t count seasonal flu deaths.

It wouldn’t take much of an error rate, in a society where 6,000 people die every day, to miss 600-700 flu-related deaths over the past 3 months. A half dozen deaths a day, or about 1 out of every 1,000 deaths, would do it.

None of this is to suggest a CFR for this virus. I certainly don’t know what that number is.

I think it is reasonably low . . . but whether it is equivalent to seasonal flu, or slightly higher or lower, I don’t think we can tell right now.

The point here is that I believe we err seriously when we try to compare the `official counted’ numbers we have from this pandemic virus against the (statistically derived) numbers we use for seasonal flu.

And I see these comparisons being made, particularly in the media by editorialists determined to downplay this pandemic, a lot.

To them, these low numbers `prove’ H1N1 is a weakling, and we are all in a tizzy over nothing.

These are really apples and oranges, each based on different methodologies, and each with their own built in sampling limitations and margins of error.

We only compound our confusion when we try to hold them up against one another.

It is an unsatisfactory answer, I know.

We all want to know just how virulent this virus is. We want to be able to point to a number and be able to say see, this virus isn’t as bad, or is only as bad as, or is only a little worse than regular flu.

The real answer is likely to vary considerably over time and by geographic region.

Some areas will probably see a milder flu, while others may see something worse. The wave this fall may be more severe, or perhaps it will be milder, than the wave we see next spring.

A pandemic isn’t some monolithic medical malady that remains constant and uniform as it spreads around the world. We can expect it to ebb and flow, simmer in some places and boil in others, and produce a wide spectrum of illness and impacts around the globe.

Undoubtedly someday epidemiologists will come up with some number that will be more-or-less agreed upon as quantifying this pandemic. And I’m sure I’ll find that number interesting.

But that may not happen until after the pandemic is history.

No matter what that number is, it probably won’t really mean much to you. What will really matter is what happens to you, your family, and your loved ones in this pandemic.

Which is why I push personal, community, and workplace preparedness so hard.

At the end of the day, everything else is just numbers.