# 4501

The panel set up by the World Health Organization (WHO) to review the global response to the 2009 pandemic has concluded their first 3-day session and will reconvene to take up the matter again in a few weeks.

John Mackenzie, an Australian who heads the committee, is quoted by Reuters as saying:

“This is just as severe as we saw in 1957 and 1968, with one major difference. We are not seeing deaths in the elderly but we are seeing them in a more important group of the population, healthy young adults.”

One might reasonably wonder how it is that we get such a wide variance in estimates and opinions of this pandemic’s impact; ranging from exceedingly mild to moderate to `as severe as we saw in 1957 and 1968’.

Last June, on the day before the declaration of pandemic phase 6 by the WHO, I described it this way:

It was six men of Indostan

To learning much inclined,

Who went to see the Elephant

(Though all of them were blind),

That each by observation

Might satisfy his mind

"The Blind Men and the Elephant"

by John Godfrey Saxe (1816-1887)

This story has been attributed to the Sufis, Jainists, Buddhists or Hindus and has been used by all of them to teach that a limited perspective can lead scholars, teachers, and clerics to the wrong conclusion.

In this story each blind man touches a different part of the elephant, and each comes away with a different opinion of what it must be.

In the Buddhist version, each person decides the elephant must be like a pot (the elephants' head), wicket basket (ear), ploughshare (tusk), plough (trunk), granary (body), pillar (foot), mortar (back), pestle (tail) or brush (tip of the tail).

And so it is with our global (and even national) influenza pandemic surveillance systems.

We see only bits and pieces of the entire picture, and must try to figure out what the entire elephant (or in this case, a pandemic) looks like based on incomplete information.

To those content to look only at officially counted influenza deaths tallied by the World Health Organization – numbers that the WHO has steadfastly maintained are incomplete and represent a significant undercount of cases – the impact of this pandemic must seem extremely mild indeed.

Fewer than 18,000 deaths have been confirmed (WHO Update Update 95).

While not insignificant, that is a fraction of the number of deaths (500K) estimated to occur during a regular flu season. By that measure, novel H1N1 saved thousands of lives over the previously circulating strains.

But of course, there’s that pesky little asterisk that reminds us that these are only lab-confirmed cases, and they only represent a small portion of the deaths attributable to the virus.

As with any disease, lab-confirmed influenza cases make up but a fraction of the total number of cases. Influenza is not a reportable disease in most countries (and only pediatric deaths are reportable in the US). And the CDC admits, even reportable diseases are often undercounted.

The CDC uses the following graphic to demonstrate that `officially reported and confirmed illnesses’ represent only the tip of the pyramid. Most illnesses, and even deaths resulting from those illnesses, must be estimated – not counted.

And this is true whether we are talking about Lyme Disease, food borne illnesses, West Nile Virus, or pandemic Influenza.

Surveillance in the United States, while far from perfect, is many orders of magnitude better than you will find in a lot of other countries. In some countries, particularly in Africa and parts of Asia, no one is bothering to count flu-related fatalities at all.

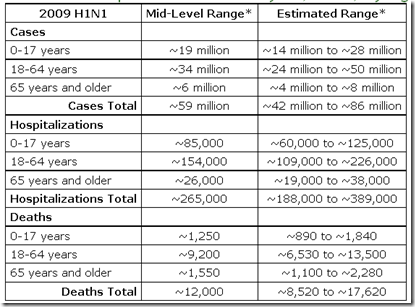

The CDC, in a attempt to better quantify the impact of the H1N1 virus in the US, has come up with a range of estimates based on limited surveillance conducted across 10 states.

Interestingly, the upper range estimate of deaths in the United States is roughly equal that of the global total number of deaths counted by the WHO.

Exactly what constitutes a `flu-related death’ isn’t well defined either.

Every day across the United States roughly 6,000 people die from a variety of causes, and even if flu played a role in their demise, it is unlikely to be identified as a factor on their death certificate. It is for this reason that the CDC uses mathematical models to estimate the number of flu deaths each year, as counting them is plainly impossible.

For more background on the difficulties in counting influenza fatalities, you may wish to revisit When No Number Is Right.

Aside from the total number of deaths due to this virus, there is also the issue the age shift to younger victims of this virus.

The average (mean) age of a flu-related fatality in a `normal’ flu season here in the United States is about 76 years. Seasonal influenza is primarily seen as a `harvester’ of the aged and infirmed, robbing its victims of the last few months or years of life.

Only rarely does it severely impact young adults and children.

When a pandemic strain emerges that pattern can change. We often see a pronounced age shift, with much younger victims. The pandemic of 2009 followed that pattern, with 85% of its victims under the age of 60.

The mean age of death from the novel H1N1 virus has been calculated to be half that of seasonal flu, or 37.4 years.

In terms of years of life lost (YLL), the average pandemic flu death has a many fold greater impact than the average seasonal flu fatality – often robbing decades of potential life from its victims.

By Cecile Viboud, Mark Miller, Don Olson, Michael Osterholm et al (5 authors)

While all deaths from influenza are tragic, it would be hard to argue that the death of a child or a younger adult doesn’t have significantly greater impact than the death of someone in their eighties.

It will likely take several years of analysis and mathematical modeling before we have a good handle on the overall impact of this pandemic. Even then, we will undoubtedly end up with an estimated range of numbers – not an official count.

The numbers from countries with little or no surveillance will likely forever remain murky.

As a blogger I’m called upon to use terms like `mild’ and `moderate’ to describe this pandemic often, and I confess to not being completely comfortable with either description.

I tend to think of the virus as being `mild for the overwhelming majority of people’, and the impact of the pandemic as being `mild-to-moderate’ - at least in the developed world.

But that hardly qualifies as a scientific assessment.

Over time we will hopefully reach some consensus over which part of the `elephant’ we should be looking at, and thereby come up with a better measure of this pandemic.

Until then, words like `mild’ and `moderate’ hold limited value.