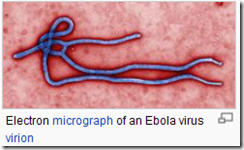

Credit Wikipedia

# 6458

For the past week the newshounds on FluTrackers have been watching reports of a `mystery disease’ in Uganda which had killed more than a dozen people, and that has now been identified as Ebola Sudan.

This morning Ronan Kelly posted the following update from the IFRC (International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies).

28 July 2012

Uganda - Information Bulletin no. 1

The situation

A deadly outbreak of Ebola has been confirmed in Kibaale Western Uganda by the Ministry of Health of

Uganda. So far, 20 cases have been reported, 13 people are reported dead, 3 cases have been admitted to Kagadi hospital and 3 patients confirmed still in the village (about 200 km from the capital Kampala). Kibaale district, in which the cases have been conformed, has a total population of about 646,700 people.

According to the World Health organization (WHO), there is no treatment and no vaccine against Ebola,

which is transmitted by close personal contact and, depending on the strain, kills up to 90 percent of those who contract the virus. WHO has also stated that the origin of the outbreak had not yet been confirmed, but 18 of the 20 cases are understood to be linked to one family.

Ebola was first discovered in Zaire and Sudan in 1976 and since then has become almost legendary for its incredibly high fatality rate and gruesome hemorrhagic symptoms.

Despite its rarity, movies like 1995’s Outbreak with Dustin Hoffman, and books like Tom Clancy’s Executive Orders and The Hot Zone by Richard Preston, have helped to turn Ebola into the ultimate nightmare disease in the eyes of the public.

While the zoonotic reservoir for the Ebola virus has yet to be firmly established, bats are considered to be the most likely candidate.

There are currently five known strains of the disease, of which four are highly pathogenic in humans. The odd virus out - Ebola Reston - which can infect and kill non-human primates, has not been shown to produce disease in man.

Almost as if a harbinger, concurrent with this week’s outbreak we’ve a dispatch that appears in the August edition of the CDC’s EID Journal regarding a single case of Ebola Sudan detected in a 12-year old girl from Uganda last year.

This dispatch provides an excellent background on the epidemiological detective work that goes on during an Ebola outbreak, along with cooperation between the CDC’s Viral Special Pathogens Branch and the Uganda Virus Research Institute.

Reemerging Sudan Ebola Virus Disease in Uganda, 2011

Trevor Shoemaker, Adam MacNeil

, Stephen Balinandi, Shelley Campbell, Joseph Francis Wamala, Laura K. McMullan, Robert Downing, Julius Lutwama, Edward Mbidde, Ute Ströher, Pierre E. Rollin, and Stuart T. Nichol

Abstract

Two large outbreaks of Ebola hemorrhagic fever occurred in Uganda in 2000 and 2007. In May 2011, we identified a single case of Sudan Ebola virus disease in Luwero District. The establishment of a permanent in-country laboratory and cooperation between international public health entities facilitated rapid outbreak response and control activities.

<SNIP>

Conclusions

We were unable to identify an epidemiologic link to any suspected EHF cases before the girl’s illness onset, or to conclusively identify a suspected environmental source of infection in and around the village in which she lived. This suggests that her exposure was zoonotic in nature and must have occurred in the vicinity of her residence, since her relatives reported that she did not travel. The fact that an additional family member had serologic evidence of an epidemiologically unrelated EBOV infection further supports the notion that zoonotic exposures have occurred in the vicinity of the case-patient’s village.

Spread of these Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers (which include Ebola, Marburg & Lassa) has thus far been geographically limited. The illness strikes quickly, with profound and debilitating symptoms, and that helps to limit human-to-human spread.

But as Maryn Mckenna pointed out in her 2010 blog Lassa fever: Coming to an airport near you, with our increasingly mobile population, opportunities for exotic tropical diseases like VHF to hop on an airplane and arrive in any major city in the world are increasing.

Despite this potential, the threat of seeing a major Ebola outbreak outside of equatorial Africa right now is pretty low. Not zero, of course.

But pretty low, nonetheless.

A interesting side note to Ebola story is that the one strain of that doesn’t cause illness in man (Ebola Reston) has been shown to cause serious illness in pigs.

Ebola Reston was first discovered in crab-eating macaques, imported from the Philippines, at a research laboratory in Reston, Virginia (USA) (hence the name) in 1989. This discovery was recounted in the book, The Hot Zone, by Richard Preston.

Since pigs and humans share many commonalities in their physiology (if that induces discomfiture in you, think how the pig feels) any disease that jumps to (and causes illness) in swine is of concern to scientists.

While humans can be infected by the this non-lethal strain (3 researchers in Reston developed high antibody titers to the virus), it has not been shown to cause human illness.

In 2009, the World Health Organization reported the following on Ebola Reston infections in humans and pigs in the Philippines.

Ebola Reston in pigs and humans in the Philippines

3 February 2009 - On 23 January 2009, the Government of the Philippines announced that a person thought to have come in contact with sick pigs had tested positive for Ebola Reston Virus (ERV) antibodies (IgG). On 30 January 2009 the Government announced that a further four individuals had been found positive for ERV antibodies: two farm workers in Bulacan and one farm worker in Pangasinan - the two farms currently under quarantine in northern Luzon because of ERV infection was found in pigs - and one butcher from a slaughterhouse in Pangasinan. The person announced on 23 January to have tested positive for ERV antibodies is reported to be a backyard pig farmer from Valenzuela City - a neighbourhood within Metro Manila.

The good news is, none of the human cases developed signs of illness.

The bad news is, that viruses can, and do, mutate over time. And we have no idea what changes would be needed to turn Ebola Reston into a pathogenic virus for humans.

Which is why the FAO, OIE, and the WHO have made it a point to track and study this virus (see FAO/OIE/WHO joint mission to the Philippines to investigate Ebola Reston virus in pigs), and why we continue to watch outbreaks of disease around the world closely for signs of changes in virulence, host range, and behavior.