Photo Credit CDC

# 6868

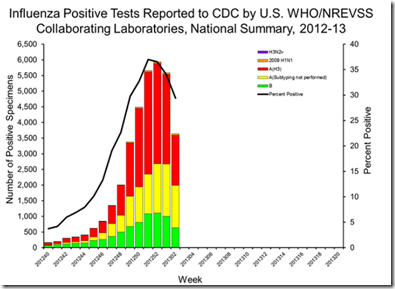

Although flu reports figure prominently in this winter’s news headlines, not every influenza-like-illness (ILI) out there is caused by an influenza virus. In fact, of the more than 12,300 specimens tested by U.S., WHO and NREVSS collaborating labs last week, less than 30% were positive for influenza.

The rest of the respiratory miseries out there are caused by a variety of viral villains (some unidentified, and some flu-negatives may really be positive), that include RSV (respiratory syncytial virus), respiratory Adenoviruses, parainfluenza viruses, rhinoviruses, coronaviruses, and metapneumovirus (to name a few).

The latest Ontario Respiratory Virus Bulletin, 2012-2013 (Week 2: January 6, 2012 – January 12, 2013) provides a fascinating graph that shows both the variety and seasonal fluctuation of respiratory viruses in institutional outbreaks over the past year.

While influenza A is the dominant player this winter, you’ll notice that last season was truly a mixed bag, with comparatively little flu. The summer months were dominated by Rhino/enterovirus detections.

The DARK BLUE part of the chart represent unidentified organisms.

The truth is - in a clinical setting - most influenza-like-illnesses go unidentified. Viral respiratory infections are generally self-limiting illnesses, treatment is pretty much the same regardless of etiology, and so there is little point in trying to identify the cause of every illness.

Scientists – with better tools available today – are indentifying `new’ viruses all of the time. A few well distributed viruses that until recently, were unknown, include:

- The human metapneumovirus (HMPV) was identified in Dutch children with bronchiolitis about a dozen years ago. Since then, it has been found to be ubiquitous around the world, and responsible for a significant percentage of childhood respiratory infections . . . yet until 2001, no one knew it existed.

- Human Bocavirus-infection (HBoV) wasn’t identified until 2005, when it was detected in 48 (9.1%) of 527 children with gastroenteritis in Spain (cite). It has since been found around the globe using PCR testing.

And the list grows longer every year.

Adding to our misery, it is fairly common to be infected by more than one virus at the same time.

In 2008 a study (see Frequent detection of viral coinfection in children hospitalized with acute respiratory tract infection using a real-time polymerase chain reaction) looked at clinical samples taken from 254 children treated in Germany over a 10 month period, finding:

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) was the most frequently detected pathogen in 112 samples (44.1%), followed by human bocavirus (hBoV) in 49 (19.3%), and rhinovirus in 17 samples (6.7%).

Viral coinfection was detected in 41 (16.1%) samples with RSV and hBoV being the most dominating combination (27 cases, 10.6%). Viral coinfection was found in 10 cases (17%) of children with bronchitis (n = 58) and in 7 cases (23%) of bronchiolitis (n = 30). In patients with pneumonia (n = 51), 17 cases (33%) were positive for 2 or more viral pathogens.

This plethora of pathogens helps to explain – in part -why so many people who get the flu shot every year complain they still caught `the flu’. Often, they’ve caught one of these ubiquitous `flu-like illnesses’.

So today, a closer look at three common non-influenza respiratory viruses, and one rare one.

RSV (Respiratory Syncytial Virus)

One of the most common infections of young children, it has been estimated that by the age of two, nearly all children in the United States have endured at least one bout with this virus.

For those wondering, `syncytial’ is pronounced (sin-SISH-uhl).

While for most people this virus produces a mild illness, often indistinguishable from a `cold’, it is also considered by the CDC to be the the primary cause of bronchiolitis (inflammation of the small airways in the lung) and pneumonia in children under 1 year of age in the United States (cite).

The CDC estimates between 75,000 and 125,000 children are hospitalized each year with RSV, and while normally thought of as a childhood illness, adults with weakened immune systems and those over 65 are also at increased risk of severe disease.

The CDC maintains an extensive RSV information page.

Respiratory Adenoviruses

With more than 50 varieties identified, respiratory adenoviruses are one of the most common causes of respiratory illness in the world.

The CDC’s Adenovirus Information page describes the virus this way:

Adenoviruses most commonly cause respiratory illness. The symptoms can range from the common cold to pneumonia, croup, and bronchitis. Depending on the type, adenoviruses can cause other illnesses such as gastroenteritis, conjunctivitis, cystitis, and less commonly, neurological disease.

Infants and people with weakened immune systems are at high risk for severe complications of adenovirus infection. Also, adenoviruses commonly cause acute respiratory illness in military recruits.

Interestingly, a person can have – and shed – adenovirus for weeks or even months without showing symptoms.

While no vaccine is currently available for the public, the military is using a recently approved (March, 2011) oral vaccine against types 4 and 7 on new recruits to help prevent outbreaks.

Over the years we’ve seen some high-profile outbreaks of adenovirus infections that have, at least until they were identified, sounded alarm bells, including China: Hebei Outbreak Identified As Adenovirus 55.

On rare occasions, outbreaks of emerging strains of adenovirus that have caused more serious illness, including one serotype (Ad14) that has been associated with a number of deaths during the past decade (see 2007 MMWR Acute Respiratory Disease Associated with Adenovirus Serotype 14 --- Four States, 2006—2007).

Parainfluenza Viruses

Human parainfluenza viruses (HPIVs) belong to the Paramyxoviridae family, of which there are 4 types (1-4) and two subtypes (4a & 4b). Each type has its own set of clinical and epidemiological features.

From the CDC’s HPIV page:

Symptoms and Illnesses

The incubation period, the time from exposure to HPIV to onset of symptoms, is generally 2 to 7 days.

- HPIV-1 and HPIV-2 are most often associated with croup (laryngotracheobronchitis). HPIV-1 often causes croup in children, whereas HPIV-2 is less frequently detected. Both types can cause upper and lower respiratory tract illnesses. People with upper respiratory tract illness may have cold-like symptoms.

- HPIV-3 is more often associated with bronchiolitis, bronchitis, and pneumonia.

- HPIV-4 is not recognized as often, but may cause mild to severe respiratory tract illnesses.

Reinfection

People can get multiple HPIV infections in their lifetime. These reinfections usually cause mild upper respiratory tract illness with cold-like symptoms. However, reinfections can cause serious lower respiratory tract illness, such as pneumonia, bronchitis, and bronchiolitis in some people. Older adults and people with compromised immune systems, in particular, have a higher risk for severe infections.

Most children 5 years of age and older have antibodies against HPIV-3 and approximately 75% have antibodies against HPIV-1 and HPIV-2.

Our last stop is with Human Enterovirus 68 (HEV68), which made headlines in 2011, but of which we’ve heard little of since. In MMWR: Clusters Of HEV68 Respiratory Infections 2008-2010 we looked at reports of six clusters of this rare, emerging enterovirus over the previous couple of years.

Enteroviruses encompass a large family of small RNA viruses that include the three Polioviruses, along with myriad non-polio serotypes of Human Rhinovirus, Coxsackievirus, echovirus, and human, porcine, and simian enteroviruses.

First detected in California in 1962, but rarely seen since that time, the CDC was notified of six clusters of HEV68 from Asia, Europe, and the United States between 2008-2010. These clusters included severe illness, and three fatalities.

Occurrence of human enterovirus 68, by month, duration, and geographic location --- Asia, Europe, and United States, 2008—2010 –MMWR

The summary provided for this MMWR release reads:

What is already known on this topic?

Human enterovirus 68 (HEV68) is a unique enterovirus that shares epidemiologic and biologic features with human rhinoviruses.

What is added by this report?

Although isolated cases of HEV68 have been reported since the virus was described in 1962, clusters of cases have been recognized only recently. The clusters described in this report occurred late in the typical enterovirus season and included severe cases, three of which were fatal.

What are the implications for public health practice?

Clinicians should be aware of HEV68 as one of many possible causes of viral respiratory disease. Some diagnostic tests might not detect HEV68 or might misidentify it as a human rhinovirus.

The number of `known’ respiratory viruses increases practically every year, due to advances in microbiology and sequence-independent amplification of viral genomes.

There is, no doubt, much more to discover about the myriad of non-influenza respiratory viruses in circulation around the world.

Most of these viruses will prove clinically indistinguishable from the respiratory viruses we already know.

But outliers like SARS CoV in 2003, HEV68 in 2008-10, or recent infections in the Middle East with the novel coronavirus EMC/2012 – all capable of producing significant levels of serious illness - show that novel viruses can emerge with little warning.

Which makes the surveillance and identification of these respiratory viruses more than just an academic exercise.