# 10,303

Although the cleanup of infected premises continues, we’ve gone roughly 3 weeks now without a new reported outbreak of avian flu, likely as a result of the warmer summer temperatures. This respite was not unexpected, and may only last a couple of more months, and so plans are being made on how to deal with the expected return of bird flu in the fall.

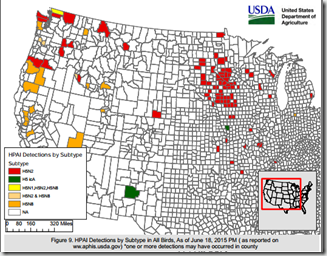

In late June the USDA released a PDF file with more than a dozen maps showing various aspects of the 2014-15 avian flu outbreak in the United States (download link) that help to illustrate not only geographic spread of these viruses, but their impact as well.

The map above shows a particularly worrisome aspect of this viral invasion, the spread of not only the originally introduced HPAI H5N8 virus, but also the detection and spread of reassortant viruses spawned from H5N8.

In this case Eurasian H5N8 – which appears to have arrived in the Pacific Northwest via migratory birds last fall – swapped genes with LPAI (low path) North American viruses and produced at least two new subtypes; HPAI H5N2 and HPAI H5N1 (North American version).

Of the three, H5N2 has done the best so far, but the fall and winter ahead represent an entirely new ballgame. We could even seen new subtypes – or fresh variations on the older subtypes – emerge when migratory birds head south this winter. The only constant with influenza is that it is always changing.

There are two broad categories of avian influenza; LPAI (Low Pathogenic Avian Influenza) and HPAI (Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza).

- LPAI viruses are quite common in wild birds, cause little illness, and only rarely death. They are not considered to be a serious health to public health. The concern is (particularly with H5 & H7 strains) that LPAI viruses have the potential to mutate into HPAI strains.

- HPAI viruses are more dangerous, can produce high morbidity and mortality in wild birds and poultry, and can sometimes infect humans with serious result. The type of bird flu scientists have been watching closely for the past decade has been HPAI H5s (and to a lesser extent HPAI H7s & H9s).

Last week, in APHIS/USDA Announce Updated Fall Surveillance Programs For Avian Flu, we looked at their concerns, and their plans to monitor birds in all four major US Flyways this fall and winter for the virus. While earlier in the month of June the CDC released a HAN (Health Alert Network) advisory on HPAI H5 Exposure, Human Health Investigations & Response.

So far, all of the North American permutations of HPAI H5 have only affected birds, and so the public health risk is considered low. These viruses are , however, related to subtypes that have caused serious human illness and even death, and therefore must be closely watched.

Even without imposing a public health risk, the economic costs of avian flu can be enormous. This past spring nearly 50 million commercial birds were lost due to outbreaks on more than 230 farms in the United States, and it can be argued that bird flu got a pretty late start last year.

The concern is we could start seeing outbreaks start much earlier this coming season, and affecting regions that previously avoided infection.

Later today (July 7th, 2015) the Senate’s Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition & Forestry will hold a hearing on the impact of Avian influenza, with experts from the USDA and the representatives from the poultry private sector.

The hearing will be web-cast live on live on ag.senate.gov at 3pm EDT.