Seasonality of H5N1 in poultry

Source FAO H5N1 HPAI Global Overview

# 10,408

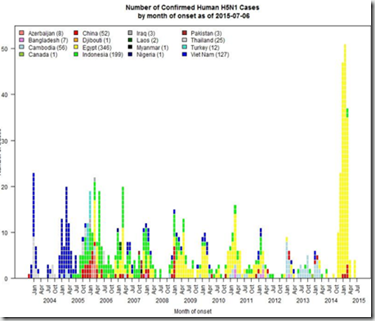

Although transmission never completely stops, since HPAI H5 viruses began circulating widely in 2003, we’ve always seen a significant lull in poultry AI outbreaks during the summer months. Like human flu, bird flu is largely seasonal, and spreads better in cooler, less humid environments.

So the usual pattern is relatively few reports between June and September, followed by a slow ramping up during the fall and winter, and peaking sometime between January and April. That pattern is also reflected in human HPAI infections (see below).

But the summer of 2015 continues to see an unseasonable number of HPAI outbreaks (in wild birds and/or poultry) around the globe. While no new outbreaks have been report in the United States since June 16th, we’ve seen numerous reports coming out of Egypt, Western Africa, parts of Europe, China, and Southeast Asia.

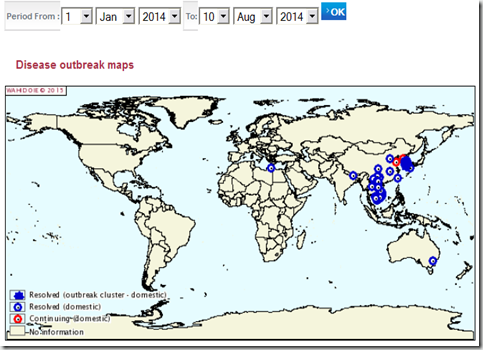

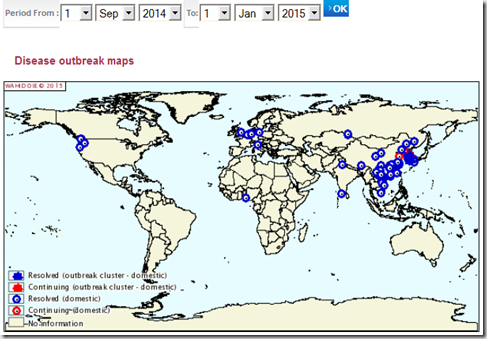

A comparison of HPAI reports to the OIE between June 1st – August 10th 2015 vs. 2014 shows this dramatic increase in summertime outbreaks.

The following maps were generated by the OIE’s WAHID Mapping tool, depicting Highly Pathogenic AI in birds. Human cases are not included. Not only are the number of reports vastly greater over the same time period, so too is the geographic range.

An even starker comparison comes when you look at the Year to Date reports for 2015 vs the same time period in 2014.

This upsurge in bird flu really began last fall, and so one more useful comparison. The fall of 2014 vs the fall of 2013. Once again we see a major increase in avian flu activity over the previous year.

After the great H5N1 Diaspora of 2006, avian flu activity began to gradually recede in 2008 and 2009, and by 2010 outbreaks were mostly confined to a handful of countries (China, Egypt, Indonesia, Bangladesh, India, etc.)

The emergence of H7N9 in China in the spring of 2013, followed quickly by the arrival of H10N8, H5N6, H5N8, has helped to reverse this trend. Of these, H7N9 and H5N8 (and its reassorted progeny) have had the biggest impact so far, but other subtypes continue to threaten.

Past performance is, of course, no guarantee of future results. In 2007, just when it looked as if avian flu was on the verge of becoming a global threat, it unexpectedly reversed course. The same thing could happen again.

But in 2007 were dealing with only one HPAI subtype of genuine concern; H5N1. Today we face a far more diverse field of subtypes circulating around the world (H5N1, H7N9, H5N8, H5N2, H5N6, H10N8, etc.), and there could be even more reassortants emerge this fall and winter.

Last February, in response to this unprecedented emergence of new flu subtypes, the remarkable and rapid spread of HPAI H5 viruses to Europe and North America, and Egypt reporting the worst human H5N1 outbreak in history, the World Health Organization released a blunt assessment called:

Warning signals from the volatile world of influenza viruses

February 2015

The current global influenza situation is characterized by a number of trends that must be closely monitored. These include: an increase in the variety of animal influenza viruses co-circulating and exchanging genetic material, giving rise to novel strains; continuing cases of human H7N9 infections in China; and a recent spurt of human H5N1 cases in Egypt. Changes in the H3N2 seasonal influenza viruses, which have affected the protection conferred by the current vaccine, are also of particular concern.

The entire report is well worth reading, but after warning that H5 viruses were currently the most obvious threat to health, they also advised:

Warning: be prepared for surprises

Though the world is better prepared for the next pandemic than ever before, it remains highly vulnerable, especially to a pandemic that causes severe disease. Nothing about influenza is predictable, including where the next pandemic might emerge and which virus might be responsible. The world was fortunate that the 2009 pandemic was relatively mild, but such good fortune is no precedent.

While I’m not making any predictions, given the unusual amount of avian flu activity we're seeing during this supposed `off season’, this may well turn out to be excellent advice.