Credit MMWR

#10,775

Updating a story I ran at the end of June (see Colorado’s Recent Spate Of Tularemia Infections), yesterday the CDC’s MMWR published a `Notes From The Field’ on the recent spike in Tularemia cases reported across four western states.

Francisella tularensis is a gram-negative coccobacillus that is zoonotic and has been reported in every state of the US except Hawaii. It is most prevalent in the south central United States, the Pacific Northwest, and parts of Massachusetts, including Martha's Vineyard.

Often a tickborne disease, Tularemia can also be spread via biting flies (deer flies), via direct contact with infected animals, and even through the inhalation of dust or aerosols contaminated with F. tularensis bacteria. It is even possible to contract the bacteria through drinking contaminated water, although this is fairly rare in the United States.

Hunters are at particular risk because of potential tick exposure and hunting activities such as skinning infected game. While often called `Rabbit Fever’, many other wild animals are known to carry this bacteria, including muskrats, prairie dogs and other rodents. The CDC warns that domestic cats are very susceptible to tularemia and have been known to transmit the bacteria to humans.

Weekly

December 4, 2015 / 64(47);1317-8

Caitlin Pedati, MD1,2; Jennifer House, DVM3; Jessica Hancock-Allen, MPH1,3; Leah Colton, PhD3; Katie Bryan, MPH4; Dustin Ortbahn5; Lon Kightlinger, PhD5; Kiersten Kugeler, PhD6; Jeannine Petersen, PhD6; Paul Mead, MD6; Tom Safranek MD2; Bryan Buss DVM2,7

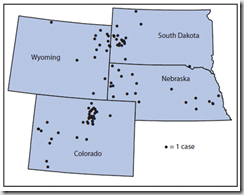

Tularemia is a rare, often serious disease caused by a gram-negative coccobacillus, Francisella tularensis, which infects humans and animals in the Northern Hemisphere (1). Approximately 125 cases have been reported annually in the United States during the last two decades (2). As of September 30, a total of 100 tularemia cases were reported in 2015 among residents of Colorado (n = 43), Nebraska (n = 21), South Dakota (n = 20), and Wyoming (n = 16) (Figure). This represents a substantial increase in the annual mean number of four (975% increase), seven (200%), seven (186%) and two (70%) cases, respectively, reported in each state during 2004–2014 (2).

Patients ranged in age from 10 months to 89 years (median = 56 years); 74 were male. The most common clinical presentations of tularemia were respiratory disease (pneumonic form, [n = 26]), skin lesions with lymphadenopathy (ulceroglandular form, [n = 26]), and a general febrile illness without localizing signs (typhoidal form, [n = 25]). Overall, 48 persons were hospitalized, and one death was reported, in a man aged 85 years. Possible reported exposure routes included animal contact (n = 51), environmental aerosolizing activities (n = 49), and arthropod bites (n = 34); a total of 41 patients reported two or more possible exposures.

Clinical presentation and severity of tularemia depends on the strain, inoculation route, and infectious dose. Tularemia can be transmitted to humans by direct contact with infected animals (e.g., rabbits or cats); ingestion of contaminated food, water, or soil; inhalation from aerosolization (e.g., landscaping, mowing over voles, hares, and rodents, or other farming activities); or arthropod bites (e.g., ticks or deer flies) (1,3). Human-to-human transmission has never been demonstrated (1,3).

(SNIP)

Although the cause for the increases in tularemia cases in Colorado, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Wyoming is unclear, possible explanations might be contributing factors, including increased rainfall promoting vegetation growth, pathogen survival, and increased rodent and rabbit populations. Increased awareness and testing since tularemia was reinstated as a nationally notifiable disease in January 2000 is also a possible explanation for the increase in the number of cases in these four states (4). Health care providers should be aware of the elevated risk for tularemia within these states* and consider a diagnosis of tularemia in any person nationwide with compatible signs and symptoms. Residents and visitors to these areas should regularly use insect repellent, wear gloves when handling animals, and avoid mowing in areas where sick or dead animals have been reported. Additional information is available at http://www.cdc.gov/tularemia.