|

| Credit WHO |

#11,300

The oral (Sabin) polio vaccine (OPV) contains three attenuated (weakened) polio virus strains that activate an immune response in the body, and for a few weeks causes the weakened virus to be shed in the feces.

This is considered a `good’ side effect, for in areas with poor sanitation, this vaccine-virus can spread in the community for a limited time conveying extra immunity.

But, as the WHO explains, every once in awhile this can go awry.

On rare occasions, if a population is seriously under-immunized, an excreted vaccine-virus can continue to circulate for an extended period of time. The longer it is allowed to survive, the more genetic changes it undergoes. In very rare instances, the vaccine-virus can genetically change into a form that can paralyse – this is what is known as a circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV).

Since 2000, more than 10 billion doses of OPV have been administered to nearly 3 billion children worldwide. As a result, more than 10 million cases of polio have been prevented, and the disease has been reduced by more than 99%. During that time, 20 cVDPV outbreaks occurred in 20 countries, resulting in 758 VDPV cases.

Statistically, a drop in the bucket. But for Polio to be completely eradicated, experts agree that the use of the OPV must be phased out, and the final push completed using the older inactivated Salk vaccine (see Nature Vaccine switch urged for polio endgame).

The first step of this big switch begins this month, where over a two-week time span the old trivalent oral vaccines around the globe will be destroyed, and replaced by a bivalent version.

The new vaccine will no longer contain the type 2 strain, which has been eradicated in the wild, and will greatly reduce the risk of re-introducing type 2 cVDPV into the population.

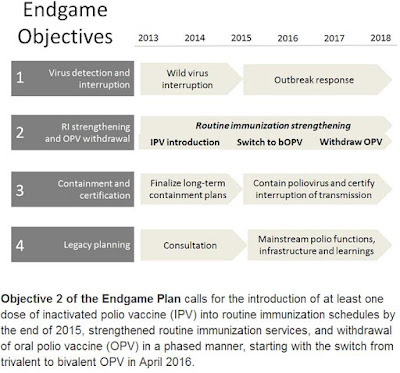

The plan is to completely phase out the bivalent OPV by 2018 (see chart below).

|

| Credit WHO |

For more on this final push to eradicate Polio, you may wish to visit:

The big switch: eradicating polio - UNICEF