|

| https://www.cdc.gov/co/default.htm |

#12,741

In my kitchen, a few feet away from the only likely source of CO gas in my home (my gas stove), I keep a carbon monoxide detector. I do so because 20 years ago my wife and I moved into an older home in another state with a faulty heater that very nearly did us in our first winter from CO poisoning.

Carbon Monoxide kills by binding to the blood’s hemoglobin at a rate many-fold faster than oxygen can. It essentially crowds out life-essential oxygen from the blood, causing those exposed to slowly suffocate . . . often completely unaware of what is happening to them.Tragically, after nearly every major disaster - when people are using camp stoves, barbecues, or generators in or near to their homes - we hear of deaths and injuries from Carbon Monoxide poisoning. Sometimes, entire involving families.

- In 2012, in MMWR: Carbon Monoxide Exposures Related To Hurricane Sandy, we looked at a preliminary MMWR report that cited more than 260 CO exposures (4 fatal) In the wake of Hurricane Sandy.

- Four years earlier, the MMWR reported 54 CO exposures following Hurricane Ike in Texas.

Summary

Carbon monoxide (CO) is an odorless, colorless, poisonous gas that can cause sudden illness and death if present in sufficient concentration in the ambient air. During a significant power outage, persons using alternative fuel or power sources such as generators or gasoline powered engine tools such as pressure washers might be exposed to toxic CO levels if the fuel or power sources are placed inside or too close to the exterior of the building causing CO to build up in the structure. The purpose of this HAN advisory is to remind clinicians evaluating persons affected by the storm to maintain a high index of suspicion for CO poisoning. Clinicians are advised to consider CO exposure and take steps to discontinue exposure to CO. Clinicians are also advised to ask a patient with CO poisoning about other people who may be exposed to the same CO exposure, such as persons living with or visiting them so they may be treated for possible CO poisoning.

Background

Hurricane Harvey made landfall between Port Aransas and Port O’Connor, Texas on August 25, 2017, causing 300,000 persons to lose power. When power outages occur during emergencies such as hurricanes or winter storms, the use of alternative sources of fuel or electricity for heating, cooling, or cooking can cause CO to build up in a home, garage, or camper and poison the people and animals inside. Although CO poisoning can be fatal to anyone, children, pregnant women, and older adults as well as persons with chronic illness are particularly vulnerable to CO poisoning. The symptoms and signs of CO poisoning are variable and nonspecific.

The most common symptoms of CO poisoning are headache, dizziness, weakness, nausea, vomiting, chest pain, and altered mental status. Symptoms of severe CO poisoning include malaise, shortness of breath, headache, nausea, chest pain, irritability, ataxia, altered mental status, other neurologic symptoms, loss of consciousness, coma, and death. Signs and clinical manifestations of severe CO poisoning include tachycardia, tachypnea, hypotension, various neurologic findings including impaired memory, cognitive and sensory disturbances, metabolic acidosis, arrhythmias, myocardial ischemia or infarction, and noncardiogenic pulmonary edema, although any organ system might be involved.

An elevated carboxyhemoglobin (COHgb) level of 2% or higher for non-smokers and 9% or higher COHgb level for smokers strongly supports a diagnosis of CO poisoning. The COHgb level must be interpreted in light of the patient’s exposure history and length of time away from CO exposure, as levels gradually fall once the patient is removed from the exposure.

With a focused history, exposure to a CO source may become apparent; items in the history that might trigger a higher index of suspicion for CO poisoning in this setting include lack of a fever, recurrent symptoms, and multiple family members affected by similar symptoms. Appropriate and prompt diagnostic testing and treatment are crucial to reduce morbidity and prevent mortality from CO poisoning.

(Continue . . . )

CO poisonings can happen anytime, and any place - not just after a disaster.

The sources of CO are numerous; faulty furnaces, snow blocked car exhaust pipes, attempts to use generators inside the house or garage . . . and the use of CO producing emergency heat sources (hibachis, BBQ grills, etc.) are among the most common.In 2005 CDC’s MMWR released a report called Unintentional Non--Fire-Related Carbon Monoxide Exposures --- United States, 2001—2003 that stated:

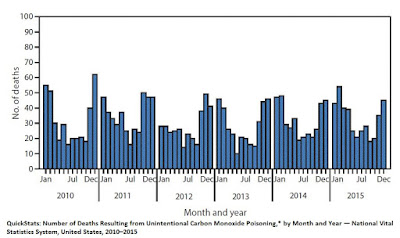

During 2001--2003, an estimated 15,200 persons with confirmed or possible non--fire-related CO exposure were treated annually in hospital EDs. In addition, during 2001--2002, an average of 480 persons died annually from non--fire-related CO poisoning. Although males and females were equally likely to visit an ED for CO exposure, males were 2.3 times more likely to die from CO poisoning. Most (64%) of the nonfatal CO exposures occurred in homes. Efforts are needed to educate the public about preventing CO exposure.A more recent MMWR Quick Stats report (Mar. 2017) illustrates how common CO exposure is in the United States, and highlights the fact that most exposures come during the winter months, when people are heating their homes.

The CDC maintains a web page on Carbon Monoxide safety , which you can access here.