#13,388

It is not exactly news that last winter's (2017-18) seasonal flu season was the worst non-pandemic flu season in recent memory, but the final tally of hospitalizations and deaths has yet to published.

Two weeks ago, we saw the CDC report Flu Deaths in Children Exceeds Seasonal High since reporting became mandatory in 2004, and the latest FluView report hospitalization chart (below) showed a 40% increase over the previous influenza season.

There is a lot of data to sift through, and while an exact count will never be known, all of the metrics to date seem to validate our perception of the severity of last winter's H3N2 flu season.

The State of Texas, which has roughly 28 million residents (a little less than 9% of the nation's total), has published their weekly influenza surveillance report (week 24), and it provides some insight into just how severe their flu really was.

Since influenza doesn't necessarily hit evenly or equally across the country, we can't just take the Texas numbers and multiply them by 11 to get a national average. But as more data from individual states become available, we should get a better idea of the national impact.The full report (link below), is well worth reading, but we'll be looking at one particular chart of interest; P&I (pneumonia & Influenza) mortality by age.

Texas Influenza Surveillance Summer Report

2017–2018 Season/2018 MMWR Week 24

(June 10, 2018 – June 16, 2018)

Report produced on 6/22/2018

P&I deaths - while a useful metric - are still unlikely to capture the full burden of influenza-related fatalities, because so many people die due to complications of influenza and are never tested for the virus.

As we've discussed previously, heart attacks and strokes are linked to recent flu infections (see Eur. Resp.J.: Influenza & Pneumonia Infections Increase Risk Of Heart Attack and Stroke) and many of those deaths are attributed to cardiovascular - not viral - causes.To be picked up by the P&I surveillance system, influenza or pneumonia has to be cited on the death certificate as being a contributing factor to a patient's death.

If the patient had cancer, or heart problems, was of advanced age, or had any other significant co-morbidity - that - not influenza or pneumonia, is usually listed as the primary cause of death.But we can only work with the numbers we have, and while the following is unlikely to be an exact count, it does provide a pretty good data point to compare to other flu seasons.

Texas reported 62 pediatric P&I deaths - while the CDC has (so far) documented 174 flu-related deaths. The CDC uses a fairly strict criteria (see below), and it isn't clear whether all of these Texas P&I pediatric cases would be included on that list.

That said, it is likely that pediatric flu-related cases are under counted every year, even with mandatory reporting. In the aftermath of the H1N1 pandemic of 2009, the CDC estimated that the likely number of pediatric deaths in the United States ranged from 910 to 1880, or anywhere from 3 to 6 times higher than reported.

Last January, in a CDC press conference, Dr. Dan Jernigan once again addressed the problem of getting a handle on the number of flu fatalities (underlining mine).

DAN JERNIGAN:

(excerpt)

So with pediatric deaths, these that are in the graphs and the ones we report again, probably also are an underestimation of the actual deaths that are out there. There may even be as much as twice than the number we have.

Among adults, those over 65 were hardest hit (7275 deaths), but more than 2,000 adults in Texas- ages 18-65 - also succumbed, bringing the the total for that one state to to almost 9,500 P&I deaths.

And that may well turn out to be a significant undercount.Last January, in Why Flu Fatality Numbers Are So Hard To Determine,

we looked at some of the statistical methodology used by the CDC, and by individual states, to come up with an estimate of the burden of influenza each winter.

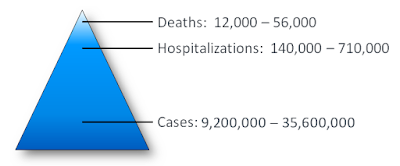

Although the CDC has an `expected range' of seasonal influenza hospitalizations and deaths (see chart below), even without a novel virus, it is possible to see an unusually severe `outlier' season.

While the full accounting has yet to be published, it seems likely - based on the numbers we've seen so far - that the 2017-18 flu season will end up being an outlier, and that its final tally will exceed the upper range of deaths and hospitalizations in the above chart.

A reminder that seasonal flu can be quite deadly, and that we take it lightly at considerable personal risk.