|

| Credit JCM |

#13,872

Influenza A & B - due to their high burden of disease and (influenza A's, in particular) wide host range and track record of occasionally mutating into a pandemic strain - remain the primary focus of influenza research.

But increasingly, attention is being paid to two other, lesser known, flu types; Influenza C & D.Influenza C infections - which were first identified in the late 1940s - are generally associated with mild respiratory illness, and are not thought to pose a pandemic threat.

A little over a week ago, however, we looked a a study in the EID Journal (see Detection of Influenza C Virus Infection Among Hospitalized Patients, Cameroon), which called for improved surveillance and more research, after detailing 3 serious Influenza C infections detected in children in Africa.After 60+ years where the influenza Universe was thought to contain only three types (A, B & C), a 4th influenza type (D) was identified - via a circuitous route - starting in 2011.

We first learned of this new flu early in 2013 when researchers reported finding a novel influenza virus in swine from Oklahoma - initially classified as a novel Influenza C virus - but which would later be designated as Influenza D.

Their research – published PLoS Pathogens – was called Isolation of a Novel Swine Influenza Virus from Oklahoma in 2011 Which Is Distantly Related to Human Influenza C Viruses, and it immediately caused a stir in the flu research community.

The authors wrote:

Based on its genetic organizational similarities to influenza C viruses this virus has been provisionally designated C/Oklahoma/1334/2011 (C/OK).

Phylogenetic analysis of the predicted viral proteins found that the divergence between C/OK and human influenza C viruses was similar to that observed between influenza A and B viruses. No cross reactivity was observed between C/OK and human influenza C viruses using hemagglutination inhibition (HI) assays.Additionally, the authors found that this new (provisional) influenza C virus could infect, and transmit, in both ferrets and pigs. The following year, in mBio: Characterizing A Novel Influenza C Virus In Bovines & Swine, cattle were added to the list, and appeared to be the virus's primary reservoir.

Since then, researchers have found evidence of a much wider spread of this virus (now officially called Influenza D) than just in the American Midwest. (see EID journal’s Influenza D Virus in Cattle, France, 2011–2014 and EID Journal: Influenza D In Cattle & Swine – Italy).

And while it isn't known if Influenza D can cause symptomatic illness in humans, in the summer of 2016 - in Serological Evidence Of Influenza D Among Persons With & Without Cattle Exposure - researchers reported finding a high prevalence of antibodies against Influenza D among people with cattle exposure. They wrote:

IDV poses a zoonotic risk to cattle-exposed workers, based on detection of high seroprevalence (94–97%). Whereas it is still unknown whether IDV causes disease in humans, our studies indicate that the virus may be an emerging pathogen among cattle-workers.

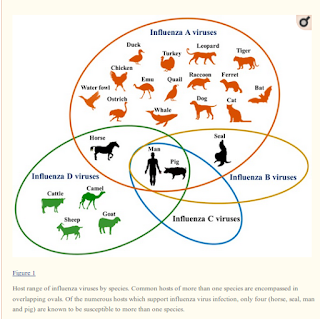

While influenza D has yet to prove itself to be a public health threat, it is worth noting that only 4 species - humans, horses, pigs, and seals - are known to be infected by more than one influenza type (A, B, C or D), and of those only 2 - humans and pigs - are believed susceptible to all four.

|

| Credit Novel Flu Viruses in Bats and Cattle: “Pushing the Envelope” of Influenza Infection |

All of which serves as prelude to an open-access article - recently published in the Journal of Clinical Medicine - which provides us with a review of what we know so far about the epidemiology, virology and pathobiology of Influenza D.

I've only included some excerpts, so follow the link to read the review in its entirety.

Emerging Influenza D Virus Threat: What We Know so Far!

Kumari Asha and Binod Kumar *

Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Chicago Medical School, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, North Chicago, IL 60064, USA

Abstract

Influenza viruses, since time immemorial, have been the major respiratory pathogen known to infect a wide variety of animals, birds and reptiles with established lineages. They belong to the family Orthomyxoviridae and cause acute respiratory illness often during local outbreaks or seasonal epidemics and occasionally during pandemics.

Recent studies have identified a new genus within the Orthomyxoviridae family. This newly identified pathogen, D/swine/Oklahoma/1334/2011 (D/OK), first identified in pigs with influenza-like illness was classified as the influenza D virus (IDV) which is distantly related to the previously characterized human influenza C virus.

Several other back-to-back studies soon suggested cattle as the natural reservoir and possible involvement of IDV in the bovine respiratory disease complex was established. Not much is known about its likelihood to cause disease in humans, but it definitely poses a potential threat as an emerging pathogen in cattle-workers.

Here, we review the evolution, epidemiology, virology and pathobiology of influenza D virus and the possibility of transmission among various hosts and potential to cause human disease.

(SNIP)

6. Conclusions

Influenza viruses have been the cause of significant concern to human and animal health worldwide. The virus not only causes morbidity and mortality, but its frequent infection also leads to socio-economic loss.

Among the four genera, the influenza A viruses have been reported to be of significant concern owing to its ability to infect a wide range of hosts, and thus gaining the potential to jump the species barrier. Wild birds are the major reservoirs of IAVs [84,85,86,87] and approximately 105 different species of birds have been reported to harbor influenza A viruses [88,89]. Most of these carriers are almost asymptomatic [90,91] and can lead to the global spread of virus as infected birds may be able to fly longer distances while on migration [92,93].

Until recently, the influenza C viruses were known to exist as a single subtype with low rates of evolution, but the newly identified IDV (isolated from pigs in Oklahoma) representing influenza-like-illness shared approximately 50% homology to human ICV. In spite of the shared homology, the antibodies raised against IDV did not neutralize the human IAV, IBV or ICV in the serological analysis, and also the IDV showed a broad cell tropism unlike ICV, thus demanding a new genus in the family Orthomyxoviridae. Soon after the identification of IDV, several countries across the globe reported similar viruses circulating in both swine and cattle population.

The novel zoonotic infections are often the result of pathogens crossing the species barrier and infecting novel host species. Although studies have shown that the IDV has not demonstrated a drastic antigenic change over the years, yet the unpredictability of influenza viruses make this type a potential health threat. IDV infections in small ruminants reported from various countries and feral swine population in the multiple states of the USA is an indication that further studies are urgently needed to clearly understand the status of IDV infections in other wild animals and the extent of interspecies transmission.

In-depth studies are required to exactly assess the economic impact of IDV infections on the commercial livestock market. The mixed reports for IDV infections in humans further make it important to study the zoonotic potential of IDV, especially in people with occupational exposure to susceptible livestock. Since IDV shows potential to infect a wide range of host after IAVs, its zoonotic potential is a global concern.While it remains to be seen whether influenza D will become a serious human health threat, it behooves us to understand it better now - while we have the luxury of time - rather than waiting until it evolves into something more challenging.

Although new studies have provided promising tools to manage IDV infections, yet more detailed investigations are needed to better understand this novel virus in terms of its epidemiological, pathological and biological characteristics specially when the capability of IDV to cause disease in humans have not been investigated in details and it’s not clear if the virus can sustain human-to-human transmission.

Advancements in several approaches to managing influenza infections have led to quick and efficient control measures that were best seen during the 2009-H1N1 pandemic when the vaccines were developed in record time. Several strategies utilizing nucleic acid-based therapeutics have also been in action against several respiratory viruses, including human influenza viruses [94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101]. It would be interesting to have such strategies against IDV for timely management of the disease in cattle and other potential hosts.

As the influenza viruses continue to evolve, there is a need of joint efforts from medical doctors, scientists, veterinarians, agricultural industry and policy makers across the world to closely monitor the circulating influenza viruses and prevent any future outbreaks.

(continue . . . )