#14,216

After a slow build up which started in 2003, between 2015 and 2017 we saw a crescendo of avian flu activity around the globe. A few highlights include:

- In the spring of 2015 Egypt reported the largest human outbreak of H5N1 on record (EID Dispatch: Increased Number Of Human H5N1 Infection – Egypt, 2014-15)

- That same spring, North America saw their largest avian epizootic in history, due to the arrival, reassortment, and spread of HPAI H5 (see A Midsummer’s HPAI H5 Snapshot).

- Over the winter of 2016-2017, Europe saw its largest avian epizootic ever, when yet another reassorted virus arrived from either Russia or China (see EID Journal: Comparison of 2016–17 and Previous Epizootics of HPAI H5 In Europe).

- And in the spring of 2017, following the emergence of new H7N9 strains, we saw largest human epidemic of avian flu on record in China (see WHO Avian Flu Risk Assessment - June 2017).

China's major decline in avian flu activity since 2017 is undoubtedly primarily due to their massive H5+H7 poultry vaccination campaign, which was initiated during the summer of 2017 and continues to this day.

As for the North American and European lulls, major bird flu seasons are often followed by one or more less active years (see chart below), likely due (in part) to acquired immunity in wild birds, and enhanced biosecurity measures taken by poultry interests.

As China has long been a prolific source of new avian flu viruses (see EID Journal: Predicting Hotspots for Influenza Virus Reassortment), their recent vaccine-induced lull has likely helped curb outbreaks around the globe.

How long that happy state of affairs will last is anyone's guess, but as the following cautionary DEFRA Situation Assessment (#6) - dated the 19th, but published on Friday - points out: we shouldn't get too comfortable with it.First some excerpts from a longer report, then I'll return with a postscript.

Updated Situation Assessment #6

Highly pathogenic avian influenza in Europe

19 July 2019

Ref: VITT/1200 HPAI in Europe

Disease report

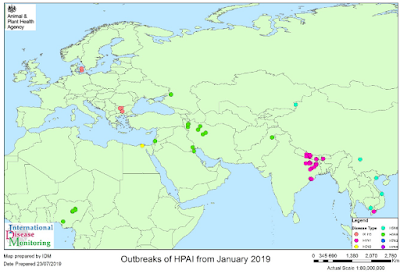

Although there have been no new outbreaks reported in Europe in the past month, or indeed since April, here we update the situation in Russia, Bulgaria and Europe since January 2019 with a summary of the outbreaks in the Middle East and central Asia.

There were relatively few highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) virus outbreaks in Europe this last winter (2018/19) when compared to H5N6 in the winter of 2017/18 and the exceptional H5N8 epizootic in 2016/17. Indeed, between October 2018 and January 2019 there were only 18 HPAI outbreaks in poultry in Europe (15 in Bulgaria and three in west Russia) and just two wild bird events, both involving birds of prey in Denmark.

Our last outbreak assessment (dated 21 January 2019) provided an update on the ongoing H5/H5N8 outbreaks in Denmark, Russia and Bulgaria.

(SNIP)

Situation assessment

In the period year to date there has been a very low level of activity in Europe and primarily associated with within sector spread and not through new primary introductions from wild birds. However the dynamics of threat from new incursions to Europe primarily mediated through wild birds is a constant, but carries uncertainties hence variability from one season to another.

HPAI events can occur throughout the year in Europe including in the summer months, but detection is only possible where there is clinical disease or high mortality. HPAI viruses remain endemic in many parts of south-east Asia and some strains could be present in the wild bird breeding areas in northern Russia, where some intermingling could occur with water bird species that will winter in western Europe this autumn.

In particular, there is overlap of the East Atlantic, Central Asian and East Asian bird migration flyways in the summer breeding sites in northern Russia. Thus, there is a pathway from the HPAI-endemic regions of south-east Asia to western Europe (Lee et al.2015).

The outbreaks in the Middle East and central Asia likely represent spread with commercial poultry and although the wild bird risk may well be very low still, these outbreaks may be relevant to Europe.

Conclusion

The OIE/FAO international reference laboratory/UK national laboratory at Weybridge has the necessary ongoing diagnostic capability for these strains of virus, whether low or high pathogenicity AI and continually monitors changes in the virus.

Currently the risk of HPAI in wild birds in the UK is LOW (i.e. no change). Although there have been no HPAI outbreaks in the UK this year and only a few in Europe (namely Bulgaria in April), this cannot be taken as reassuring regarding the risk for incursions this coming winter. This can be linked to the fact that there may be now more limited immunity in the wild bird population to H5 viruses, with a large susceptible population of hosts in the form of juvenile birds migrating to the UK every autumn.

Furthermore, as can occur every year, the current virus strains are continually evolving especially in central and eastern Asia where they circulate more freely and may be changing to escape the existing immunity at population level. Spread of such viruses amongst migratory waterfowl whilst on their breeding grounds in the far north of Russia in the summer is a mechanism that is well defined and could reoccur during 2019.

The north-east migration pathway to Europe and the UK is of key importance and it is possible that H5N6 could re-emerge this autumn in western Europe. The diversity of strains and virus genetic mixing events together with weather conditions and wild bird immunity make predictions on HPAI spread risk not possible at the present time.

However taking historical events into account years/seasons of relatively low activity can be followed by those of high activity.

Therefore, we recommend that all poultry keepers stay vigilant and make themselves aware of the latest information on gov.uk, particularly about recommendations for biosecurity and how to register their flocks using the simplified forms now available.

We will continue to report on any updates to the situation and in particular any changes in disease distribution or wild bird movements which may increase the risk to the UK.

(Continue . . . )

Last November the WHO issued a similar warning (see WHO: Migratory Birds & The Potential Spread Of Avian Influenza), and while Europe and Asia were largely spared, Egypt saw the arrival of a newly reassorted H5N2 virus, and India and Nepal saw outbreaks of H5N1.

The major migratory bird flyways shown below - along with scores of minor pathways not depicted - serve as a global interstate highway for avian influenza viruses. While primarily north-south conduits, there is enough overlap to allow for east-west movement as well.

A study, published in 2016 (see Sci Repts.: Southward Autumn Migration Of Waterfowl Facilitates Transmission Of HPAI H5N1), suggests that waterfowl pick up new HPAI viruses in the spring (likely from poultry or terrestrial birds) on their northbound trip to their summer breeding spots - where they spread and potentially evolve - and then redistribute them on their southbound journey the following fall.

All of which means that - despite the relative quiescence of the past 24 months - this fall we'll be once again on the lookout for any signs of renewed avian flu activity around the world, and the potential for seeing new reassortant viruses in the mix.