#14,209

Zoonotic diseases are those which originated in or are normally hosted by non-human species - but can spill over into human. In 2014, in Emerging zoonotic viral diseases L.-F. Wang (1, 2) * & G. Crameri wrote:

The last 30 years have seen a rise in emerging infectious diseases in humans and of these over 70% are zoonotic (2, 3). Zoonotic infections are not new. They have always featured among the wide range of human diseases and most, e.g. anthrax, tuberculosis, plague, yellow fever and influenza, have come from domestic animals, poultry and livestock.

However, with changes in the environment, human behaviour and habitat, increasingly these infections are emerging from wildlife species.These emerging infectious diseases are considered such an important threat that the CDC maintains as special division – NCEZID (National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases) – to deal with them.

Last May, in CDC: The 8 Zoonotic Diseases Of Most Concern In The United States, we looked at a newly published 68-page One Health Zoonotic Disease Prioritization report, that identified the top 56 threats to the United States.

Number 10 on that list was CWD - Chronic Wasting Disease - a disease of Cervids (deer, moose, elk, etc.) - which has yet to be detected in humans, but is strongly suspected of having zoonotic potential. They wrote:

CWD was suggested to be kept on the initial list for consideration because even though no human cases have been detected, CWD falls within a class of pathogens that includes some that have been show to infect humans (namely, BSE).

There is also evolving laboratory animal data showing transmission of CWD to macaques through feeding of meat from infected animal, which heightens our concerns for potential zoonotic transmission.

Due to the unique circumstances of prion diseases—including a long and unpredictable incubation period that could be years or even decades—long-term surveillance is needed to know whether or not human infections could be occurring. For this reason, the “question” of CWD as a zoonotic disease has been approached with a strong One Health purpose.Considering the amount of deer meat consumed every year in this country - and elsewhere - determining whether or not CWD poses a substantial risk to humans is a pretty high priority.

All of which brings us to an opinion/hypothesis piece published today in the journal mBio, which looks at the history of prion disease in humans, the difficulties of detecting the disease, and the potential threat to humans and other animals.The article is authored by Dr. Michael Osterholm (Director of CIDRAP) et al., and while definitive answers as to CWD's risk to public health remain elusive, there are enough concerns to warrant increased suveillance and research.

I've only posted a few excerpts from an extremely well-written and informative article. I would highly recommend you follow the link below and read it in its entirety.

(SNIP)

CHRONIC WASTING DISEASE: BACKGROUND

Chronic wasting disease (CWD) is a TSE that affects cervids, including deer, elk, reindeer, sika deer, and moose. It was first identified in 1967 in a captive mule deer living in a Colorado research facility.

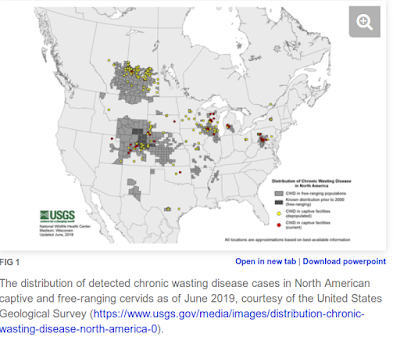

The increasing CWD disease risk in cervids is evident from surveillance data; in 2000, CWD was documented in five U.S. states and one Canadian province, in 2010, it was identified in 17 states and two provinces, and in 2018, it was found in 26 states and three provinces (Fig. 1). CWD has also been documented in South Korea, Finland, Norway, and Sweden.

The disease is most likely transmitted horizontally through infectious bodily fluids such as saliva, urine, and feces (11). Once excreted into the environment, CWD prions can persist for years (12, 13) and withstand extremely high levels of disinfectants such as heat, radiation, and formaldehyde (14). CWD prions also appear to be capable of binding to certain plants, with the ability to be transported while still potentially remaining infectious (15).

CWD is increasing in cervids as more animals come into contact with infectious prions, usually via direct contact with an infected cervid and its bodily fluids, although viable CWD prions in the environment can also infect animals (14). As more cervids become infected, the frequency of these exposures and subsequent environmental contamination grows. (SNIP)

As a result of ongoing transmission among cervids, the frequency of human exposure to CWD prions is likely growing. The Alliance for Public Wildlife estimates that 7,000 to 15,000 CWD-infected animals are consumed annually, a number that may increase by 20% each year (17).

(SNIP)

CONCLUSION

Available data indicate that the incidence of CWD in cervids is increasing and that the potential exists for transmission to humans and subsequent human disease. Given the long incubation period of prion-associated conditions, improving public health measures now to prevent human exposure to CWD prions and to further understand the potential risk to humans may reduce the likelihood of a BSE-like event in the years to come.

Copyright © 2019 Osterholm et al.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

(Continue . . . )